From Our Archives

For earlier essays on this week's RCL texts, see Michael Fitzpatrick, The Lord’s Mind was Changed (2022); Debie Thomas, On Lostness (2019); Dan Clendenin, A Trustworthy Saying (2016), and Aelwyd a Gymhell: What I Learned in Wales this Summer (2013).

This Week's Essay

By Amy Frykholm, who writes the lectionary essay every week for JWJ.

Luke 15:6: “Rejoice with me, for I have found my lost sheep.”

For Sunday September 14, 2025

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year C)

Psalm 14 or Psalm 51:1–11

1 Timothy 1:12–17

Luke 15:1–10

I had been following rumors for weeks about a Chapel of Mary of Egypt at the Church of the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem. Now I was finally standing in the office of the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate with Bishop Isidoros. This small man with twinkling eyes and a long black beard had confirmed the chapel’s existence, but he wasn’t sure where the key was. It had been many years, he said, since the chapel had been open. While I waited for him to look for the key, he suggested I venerate the remnants of the Holy Cross, in a side room off the main office space.

Several years before this, I had become intrigued by the ancient saint, Mary of Egypt. Her story was told in a seventh-century manuscript written by St. Sophronius called The Life of Mary of Egypt, and I had stumbled across a translation that had riveted me.

According to Sophronius, Mary was a child runaway who became a prostitute in the city of Alexandria. In her late twenties, she decided to join pilgrims who were setting out on the Mediterranean Sea to Jerusalem for the Feast of the Holy Cross. Because she had no money, she sold sex to these pilgrims to pay for her passage.

In the courtyard of the Church of the Holy Sepulcher, she had a spiritual encounter with an icon of the Virgin Mary and was directed to go into the desert, to “cross the river and find a beautiful rest.” She followed these mysterious instructions, left Jerusalem, walked along the Wadi Qelt, and crossed the Jordan in a little boat before disappearing into the wilderness.

She lived there for the rest of her life, until she was “found” by Zosimas, a life-long monk whose spiritual path had grown faint and who was on his own quest for healing and salvation. It is a moving story about freedom and self-determination, along with devotion, desire, and divine help — strange and wonderful — and I had fallen in love with it.

|

|

Anonymous, Icon of Mary of Egypt.

|

The Feast of the Holy Cross (traditionally celebrated on September 13) was first commemorated to celebrate the “finding of the True Cross” by Emperor Constantine’s mother Helen when she ventured to Jerusalem in 326. She had traveled to the lands of the Bible to find remnants of specific events. Tradition has it she “found” the location of the burning bush and the place of the nativity, among many other things, as well as these remnants of the cross in front of me. One tour guide I heard in the courtyard of the Sepulcher claimed loudly that Empress Helen “tortured” local people for information. I admit, I had trouble making sense of all of this: a quest for the exact objects and locations of biblical stories seemed as misguided as my own journey to find someone who might never have actually existed. I probably should have seen in Helen a kindred spirit, but instead I felt alienated from these remnants.

As a life-long Protestant, I didn’t know how to venerate. I watched some Greek pilgrims bow swiftly, with practiced grace, and bend their foreheads to the glass case and kiss it. After they left, I stood in front of it, bowed my head, and hoped the bishop would return soon. Then I bent my lips awkwardly toward this remnant of the True Cross and kissed the glass, feeling like an absolute fake.

Using Sophronius's The Life of Mary of Egypt as a kind of map, I had started my own pilgrimage in Upper Egypt and intended to make my way to the wilderness of Jordan where I understood that Mary had ended her holy life, “deep in the heart of the desert.” Jerusalem was the midway point in Mary’s journey and in mine.

|

|

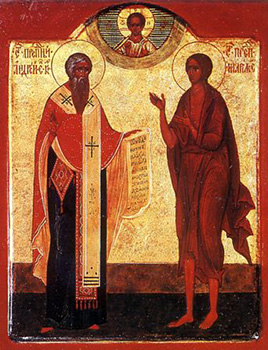

Anonymous, Icon of Mary of Egypt with Andrew of Crete.

|

But it wasn’t like Mary was waiting for me on the other side of the world. My quest often felt like a game of hide and seek. Maybe I would catch glimpses of her, but the world had moved on. She had long been forgotten. When I said her name, most people looked at me puzzled or thought that I must be referring to Mary, the mother of Jesus. The Chapel of Mary of Egypt was the first tangible sign of her that I had found.

When Bishop Isidoros returned with an oversized iron key that looked like something out of a fairy tale, he led me out into the bright sunshine of the courtyard. There he unlocked the door to a tiny room he said was the Chapel of Mary of Egypt. Inside was almost nothing: a dirt floor, a neglected iconostasis, a small window, and a few remnant building materials. It was like looking into a friend’s abandoned apartment. It was clear she wasn’t here.

“There’s a plan for renovation,” Bishop Isidoros said, perhaps perceiving how neglected the place looked through my eyes.

“Does anyone ever ask about this chapel?” I asked.

“No,” he shook his head and smiled kindly.

I had spent many weeks in Jerusalem looking for this chapel. Now finding it, I wanted to cry, but I wasn’t sure why. I thought of my new friend, Dan, telling me in a coffee shop in Bethlehem, “Don’t be surprised if she’s not in Jerusalem.” He was the only other person I’d met willing to talk about Mary of Egypt like she was a real person, waiting for us out in the desert somewhere.

|

|

Anonymous, Icon of Mary of Egypt and Scenes from Her Life (c. 1650). |

Many miles and days later, I myself crossed the Jordan, and I stumbled on the place where Mary had lived, taught, and was commemorated by thousands of pilgrims for hundreds of years. In between, as I walked from Jerusalem to the Jordan, I had a lot of time to think about finding and losing — and the paradoxes involved. In the parables for this week's lectionary in Luke 15 about the lost sheep and the lost coin, Jesus clearly delineates between the one who is seeking and the one who is lost. But as I went, I felt like both the seeker and the hidden one. Seeking and finding wasn’t a one-time event, but an ever-ongoing process.

In Sophronius's The Life of Mary of Egypt, there is a poignant moment when the monk, Zosimas, finally catches up with the elusive Mary in the desert. He has left everything he’s ever known and loved because he recognizes that on his path of self-perfection, he’s lost something precious. A mysterious teacher tells him that he must go deeper into the desert in order to learn “how many roads there are to salvation.”

When he catches a glimpse of Mary in the desert, he thinks she is a spiritual father who will teach him what he’s given up so much to learn. But instead she runs away from him. He runs after her, in tears, exhausted but persistent. They reach the bank of a stream bed, and Mary leaps to the far side. He calls out after her in despair, “Why are you fleeing an old man and a sinner?” And then in a broken voice, "God does not ever detest anyone.”

At that moment of loss and self-recognition, she finally turns toward him, in her vulnerability and nakedness, and allows him to come closer. The one who was lost allows herself to be found, but as Zosimas later tells us, "He could not hold for long, she who would not be held."

*See Amy Frykholm, Wild Woman: A Footnote, the Desert, and My Quest for an Elusive Saint (Broadleaf, 2021).

Weekly Prayer

Bernard de Clairvaux (1090–1153)

Of Him Who did salvation bring,

I could forever think and sing:

Arise, ye needy, He’ll relieve;

Arise, ye guilty, He’ll forgive.

Ask but His grace, and lo, ’tis given!

Ask, and He turns your hell to heaven;

Though sin and sorrow wound my soul,

Jesus, Thy balm will make it whole.

To shame our sins He blushed in blood;

He closed His eyes to show us God:

Let all the world fall down and know

That none but God such love can show.

Insatiate to this Spring I fly;

I drink, and yet am ever dry;

Ah! who against Thy charm is proof!

Ah! who that loves, can love enough?Translated by Martin Madan.

Bernard de Clairvaux (1090–1153) was an abbot, mystic, and co-founder of the Knights Templar. He led reform of the Benedictines through the nascent Cistercian Order.

Amy Frykholm: amy@journeywithjesus.net

Image credits: (1) Wikimedia.org; (2) Wikimedia.org; and (3) Wikimedia.org.