From Our Archives

For earlier essays on this week's RCL texts, see Michael Fitzpatrick, If We Do Not Work, We Should Not Eat? (2022); Debie Thomas, "By Your Endurance" (2019); Dan Clendenin, Come By Here: America's Presidential Election (2016), and "Don't Grow Tired of Doing Good" (2013).

This Week’s Essay

By Amy Frykholm, who writes the lectionary essay every week for JWJ.

Isaiah 65:23: “They shall not labor in vain or bear children for calamity.”

For Sunday November 16, 2025

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year C)

Isaiah 12 or Psalm 98

2 Thessalonians 3:6–13

Luke 21:5–19

In the fall of 2003, I was a Fulbright scholar in Kyiv, Ukraine. A Ukrainian colleague invited my husband, my 18 month-old son and me to the city of Luhansk, on the far eastern edge of Ukraine. His daughter Natasha and son-in-law Roman were celebrating the birthday of their year-old son, Dima, by hosting a big party at the family home.

The celebration was elaborate. Food was two full days in preparation: endless salads, cabbage rolls, mashed potatoes with chicken gravy, all manner of sausage, meat cutlets, and several elaborately layered cakes. The drinks included champagne, cognac, wine, spiced honey vodka, and homemade cherry compote.

At one point during the celebration, the family enacted an old tradition. They spread a blanket on the floor and placed household objects across it: a hammer, a book, a dollar bill, a vodka bottle, among other things. Dima was then led to the blanket. Whatever item he gravitated to first was the symbol of his future. The hammer meant he would work as a skilled craftsman. The book suggested the life of a scholar. The dollar bill presumed he would work as a biznesmyen — a term and concept awkwardly entering the language and culture. The vodka bottle portended a life as a lazy idler.

To cheers and encouragement, both boys — Dima and my son — were invited to pick an item from the blanket, and then jokes about their choices abounded. The atmosphere was light and optimistic. The sense that our children could choose their futures, a belief belied by centuries of Ukrainian history, was palpable.

Twelve years later we returned to Ukraine to visit this family. We’d kept marginally in touch and were eager to reconnect with one another’s lives. The country and the family had changed. In the winter of the previous year, Ukraine had experienced the Revolution of Dignity. Through protests that killed more than 100 people, Ukrainians had ousted their corrupt, Russian-leaning president Viktor Yanukovych and held democratic elections. In response, Russia seized the Ukrainian territory of Crimea and fomented armed conflicts in the eastern part of the country in order to destabilize the Ukrainian government still further.

|

|

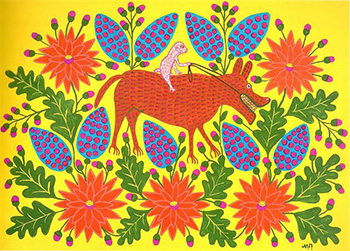

Maria Prymachenko, A Lamb Has Harnessed a Wolf (1969).

|

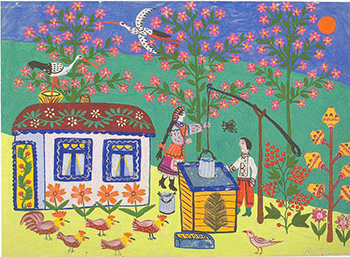

With armed clashes now engulfing Luhansk, Natasha and Roman abandoned their home and moved to Kyiv, some 500 miles from the front. The family of now four generations was packed into two apartments, and everyone was feeling the strain of the displacement. Working together, pooling their resources, they were finding a way forward, but the difficulty was evident.

Dima and his little brother, Vova, were both bright boys. Dima was shy and loved dance and Lego robotics. Whenever anyone asked him about his future, he would shrug and change the subject to what he was learning in school.

For the next eight years of his adolescence, the war was fought on the edge of the country and had little effect on his daily life in the capital. He went to school, competed in robotics and dance festivals, and entered a technical institute. The normalcy of life in Kyiv, contrasted with the violence and suffering in eastern Ukraine, proved something of a disconnect. As his grandmother told us, “Half the country is laughing and half the country is crying.”

Then came February 24, 2022 when Russia launched its full-scale invasion in an attempt to topple the government and turn Ukraine into a Russian territory. Today, nearly four years into the war and under nightly bombardment, the family tries to make sense of Dima’s options. He is just three years from the age of conscription into the Ukrainian army, with political pressure mounting to lower that age. The conflict appears to be a long, drawn out one with no end in sight. Tens of thousands of Ukrainians have already died in the fighting. It hardly matters if one-year-old Dima had reached for the hammer or the book or the dollar bill. His fate seems to be in others’ hands.

|

|

Maria Prymachenko, At the Well (1969).

|

I thought about Dima and his family as I read Isaiah 65 in this week’s set of lectionary texts. Maybe it was the line, “They shall not labor in vain or bear children for calamity.” Those final words arrested me. What if it were my son, awaiting calamity? As I paused and tried to feel that for a single second, in its fullness, I found myself swerving almost desperately into abstractions.

In some ways the vision for human flourishing in this text is strikingly basic and simple: people will experience full and long lives. “They shall build houses and inhabit them; they shall plant vineyards and eat their fruit” (Isaiah 65:21). Other people won’t live in the houses they’ve built or eat the fruits of their labor. They “shall long enjoy the work of their hands” (Isaiah 65:22).

Build a house and live peacefully in it. Plant a garden and eat from it, year upon year. How rare in the course of human history has this been? Right now, according to UN estimates, there are around 120 million displaced people in the world. Forced displacement nearly doubled in the last decade, and through 2024 it had reached record high levels for 12 consecutive years.

To these millions, the vision of Isaiah, simple as it is, hovers out of reach. To Natasha and Roman, the prophecy of peace and stability is as unlikely as the idea of a wolf and a lamb feeding together or a lion suddenly opting to eat straw (Isaiah 65:25). Far more likely, at this point, is that two wolves will get together and divide up the lambs to their liking. In fact, a wish for an alternative feels like it belongs to a completely different world, a world where wolves are not wolves and lions are not lions.

Between verse 23 and verse 25 there is a turn. One kind of language and image replaces another. In verse 23, the text speaks in terms of building a house, planting a vineyard, and raising a child. In verse 25, the text offers the unimaginable: “wolf and lamb shall feed together.” One is a hopeful possibility of the world we live in. The other is something we can’t know in the way this world is put together.

Between the two is a word about prayer in the prophetic vision that Isaiah offers. “Before [the people] call I will answer, while they are yet speaking I will hear” (Isaiah 65:24). In this line, the prophet declares that the gap between the human and the divine will narrow or even perhaps collapse. No longer will we pray and hear nothing in response. Instead, we will not even need to pray, so closely will our own realities be aligned with the will of God.

|

|

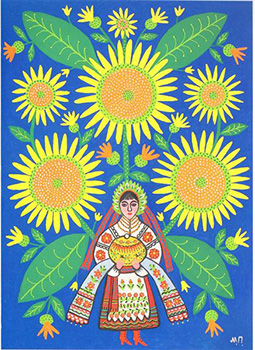

Maria Prymachenko, I Give This Ukrainian Bread to All People in the World (1982).

|

After the full-scale invasion began, Natasha’s sister, Alya, made a radical decision. Twenty-five years after she had first given birth, she had another child. It was a defiant act of hope, of optimism, of love. “We won’t,” she wrote to me, “we can’t, allow Putin to determine our future.”

I am hesitant to write this because a child is not a symbol. A child is a human being who will grow up in this world in the midst of circumstances that she cannot control, that her parents, her community, and her nation cannot control. But I feel in Alya’s choice what Frederich Nietzsche called hope’s “tender and graceful audacity,” something born mysteriously from the painful reality through which Alya lives.

I’ve come to think of prophecy as what literary critic Raymond Williams would call “a structure of feeling.” Prophecy is not a prediction. It’s an attempt, through language, to hold together despair, longing, fear, and hope at once in your own being and in the life of a community. Maybe, in order to do that, the deepest of the feelings has to be longing, perhaps what Julian of Norwich would call love-longing. “Love-longing lasts and ever shall,” Julian wrote in the midst her own calamities, “until we see that sight on the last day.”

Weekly Prayer

George MacLeod (1895-1991)

Almighty God …

Sun behind all suns,

soul within all souls …

Show to us in everything we touch and in everyone we meet

the continued assurance of thy presence round us,

lest ever we should think thee absent.

In all created things thou art there.

In every friend we have

the sunshine of thy presence is shown forth.

In every enemy that seems to cross our path,

thou art there within the cloud

to challenge us to love.

Show to us the glory in the grey.

Awake for us thy presence in the very storm

till all our joys are seen as thee

and all our trivial tasks emerge as priestly sacraments

in the universal temple of thy love.George MacLeod (1895–1991) was one of the most important and unconventional ministers of the Church of Scotland in his day. He founded the Iona Community on the island of the same name. This poem comes from The Whole Earth Shall Cry Glory: Iona Prayers (Wild Goose Publications, 2007), p.13–14.

Amy Frykholm: amy@journeywithjesus.net