From Our Archives

For earlier essays on this week's RCL texts, see Dan Clendenin, Yes, I am a King (2022); Debie Thomas, A King Like No Other (2019) and A King for This Hour (2016); Dan Clendenin, They Say There Is Another King, One Called Jesus (2013), "Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews": The Feast of Christ the King (2010) and The Absence of God's Presence (2007).

This Week's Essay

By Amy Frykholm, who writes the lectionary essay every week for JWJ.

Colossians 1:17: “He himself is before all things, and in him all things hold together.”

For Sunday November 23, 2025

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year C)

Luke 1:68–79 or Psalm 46

Colossians 1:11–20

Luke 23:33–43

The readings this week invite us to explore the traditional and deeply discomforting theme of Christ the King. Here in the United States, we've got the extra challenge of contemplating Christ the King in our “No Kings” moment, as we leave ordinary time behind and enter into a set of sacred seasons.

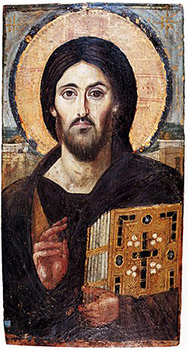

I decided to address this challenge by contemplating a little icon in my house. It's Christ Pantocrator (Christ Ruler of All). It sits on a bookshelf in front of BK Loren’s Theft and Norman Mailer’s Why Are We In Vietnam?, flanked by icons of St. Mary on one side and St. Nicholas on the other. I was given this icon many years ago, so long ago now that I no longer remember when or by whom.

Despite its rather humble place in my house, this icon is the foremost of all icons. It is the most copied, and it summarizes the doctrine of the Council of Chalcedon (451 CE) in one arresting image. This image stares down from the ceiling of many Orthodox churches and attempts to communicate that Jesus is fully human and fully divine.

To read the icon, says Episcopal priest and icon writer Mary Green, look at the halo first. The halo encircles a cross. This in itself is almost enough: Christ’s holiness is understood through the cross, where his human and divine natures come together.

|

|

|

Christ Pantocrator, Patmos.

|

Written on the cross are three Greek letters: O—Omicron, Ω—Omega, N—Nu. These three letters represent the Greek phrase “Ὁ ΩΝ,” Ho On, the One Who Is. The phrase echoes in Greek what we learn about the divine nature in Exodus when Moses asks the presence at the burning bush, “Who are you?” and the presence answers, Ehyeh asher ehyeh, “I am who I am.”

In the top left and top right corners are more Greek letters: IC XC. These are the first and last letters of Jesus’ earthly name (Iesous) and the first and last letters of his divine name (Christos). Christos is the Greek translation of the Hebrew Messiah, or Anointed One.

In this icon, Christ wears two garments. The inner garment is red. In iconography red is the color of divinity, but also the color of incarnation and passion. The outer garment is blue — the color of humanity, “born in human likeness,” as Philippians 2:7 puts it. The outer garment is the one that Christ “puts on” when he comes to earth as Word Made Flesh.

In Christ’s left hand, he holds a book, indicating his role as logos, the Word of God. He raises his right hand in blessing.

The figure of Christ himself appears flat and two dimensional. This is an intentional aspect of a written icon, perhaps the most important part. An icon is meant to act as a window. A window allows you to see from the inside out and from the outside in, and it allows light to pass through. In prayer, an icon can illuminate you, illuminate the holy one in the icon, and illuminate the divine as it shines through.

|

|

Christ Pantocrator, St. Catherine’s Monastery, Sinai (c.550 CE).

|

In Christ Pantocrator, in particular, we are meant to see the central paradox of Christian doctrine: that Christ is fully human and fully divine. In the earliest known icon of this type, written perhaps in the mid-sixth century and held at St. Catherine’s Monastery at Mt. Sinai in Egypt, the icon writer included two different sides of Jesus’ face, what’s called a “double gaze.” This “double gaze” has been subject to many interpretations, including that one side of Jesus’ face is meant to reflect mercy and the other judgment. The effect is quite strange, but strange is perhaps the point.

Christ Pantocrator is in visual imagery what this week’s lectionary readings are in words: a representation of the paradoxical nature of our faith. Paradoxes abound in these readings. In one such paradoxical statement, the psalmist points to both the power and the stillness of God, “See what desolations he brings down/He makes wars cease to the ends of the earth” (Psalm 46:9). God is both peace and fury. Calm and storm. In Colossians, Christ is eternal; in Luke 23, Christ is mortal. In Colossians, he reigns. In Luke, he dies.

Along with these paradoxes, we have images and words of reconciliation, of the bringing together of disparate things. “In him all things hold together,” Colossians says. In the end, the predominant theme is peace.

Because it is difficult to hold these mysteries in our human minds, the text offers some advice. “Because of the tender mercy of our God,” sings the Canticle of Zechariah, “the dawn from on high will break upon us, to shine upon those who sit in darkness and in the shadow of death, to guide our feet into the way of peace” (Luke 1:78–79).

This offers a clue for how the passages can be read. First, we sit in darkness. We let the truth of our unknowing, of the mystery of “the One Who Is,” be with us. Then “the dawn from on high will break upon us,” and will “guide our feet in the way of peace.”

|

|

Christ Pantocrator, Church of the Holy Sepulcher, Jerusalem.

|

Raimon Panikkar, a Spanish Catholic priest, interfaith scholar, and interpreter of Christianity, maintains that the image of Christ Pantocrator is actually an image of each one of us. As different, as far off as these images of Christ can seem, the paradox is that each one of us is a christophany, a manifestation of the transcendent and the immanent.

Each of us is “the christic adventure of the whole of reality on its way to the infinite mystery.” In this reading, Christ Pantocrator is saying something, not just about Christ, the One Who Is, but also about All That Is — the infusion of all phania with divine reality.

The point of the Christ Pantocrator icon, however, is not to be examined, not to be understood or interpreted. It is to be contemplated. At the heart of Psalm 46, amidst the earth shaking and the mountains falling, there is a line that has guided Christians into contemplative prayer for thousands of years. “Be still and know that I am God” (Psalm 46:10). Perhaps the most difficult and most important “reading” of this icon is simply to be with it, to sit in its presence, to allow, in one more paradoxical moment, its silence to be its speech.

Weekly Prayer

Nicholas Samaras (b.1952)

Then, the Lord heard me in the wilderness of my soul.

Then, the lost place of me became clear.

Then, I recognized distraction for what it is.

Then, I was freed from the desert of diversion.

Then, I was moved to the green oasis within me.

Then, the still voice of the Lord was as the depth of water.

Then, I could cease the constant music in my head.

Then, I could move beyond myself and the noise of myself.

Then, I could hear the smallness of my own voice.

Then, the still voice of the Lord was as the depth of water.

Then, the lost place of me became clear as a cascade.

Then, I could hear the bass of my name.

Then, I heard the Lord in the wilderness of my soul.

Then, stillness and stillness and stillness sang.Nicholas Samaras (b.1952) is from Patmos, Greece. At the time of the Greek junta military dictatorship, he was brought as a child to America. He has lived in Greece, England, Wales, Belgium, Switzerland, Italy, Austria, Germany, Yugoslavia, Jerusalem, and thirteen states in America. He describes his writing as coming from a permanent place of exile. His first book, Hands of the Saddlemaker, won the Yale Series of Younger Poets award. This poem is from American Psalm, World Psalm (Ashland Poetry Press, 2014).

Amy Frykholm: amy@journeywithjesus.net

Image credits: (1) Saint Paul's Monastery, Marietta, Wisconsin, USA; (2) Wikipedia.org; and (3) Wikipedia.org.