From Our Archives

For earlier essays on this week's RCL texts, see Dan Clendenin, Zacchaeus: The Tale of a Tax Collector (2022); Debie Thomas, When Salvation Comes (2019) and Learning to See (2016); Helen Brooks, Reformation Sunday (2010); Sam Rowen, Remembering the Protestant Reformation (2007).

This Week's Essay

By Amy Frykholm, who writes the lectionary essay every week for JWJ.

Luke 19:4: “So he ran ahead and climbed a sycamore tree to see him.”

For Sunday November 2, 2025

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year C)

Psalm 119:137–144 or Psalm 32:1–7

2 Thessalonians 1:1–4, 11–12

Luke 19:1–10

In Egypt, north of Cairo, there is a sycamore tree called The Tree of the Virgin. Tradition has it that the Holy Family sought shelter under its branches on their flight to Egypt.

The sycamore has been cultivated by people in the Middle East for thousands of years. At the pilgrimage site, gardeners take branches from dying sycamores and replant them so that each subsequent sycamore tree is a relative of the one that came before.

The current tree in this spot is said to have descended from one that fell in 1906 and before that in 1672. Coptic pilgrims from all over the world come to this tree to seek healing and connection. They touch the tree and then rub their faces and their hearts, as if, writes journalist Susan Sachs, “to absorb its essence.”

At the center of Luke 19 is the same tree: the sycamore, ficus sycomorus, one of the most ancient and most revered trees in the lexicon of the Middle East. The sycamore stands so quietly, it would be easy to miss, seeing it as just a backdrop to the human drama unfolding in and beneath it. But, as is often the case with less noticed things, when we pay attention to it, the story we’re telling changes.

The sycamore is a broad-crowned tree, whose bark exfoliates in papery strips. The thick and gnarled trunk often develops deep fissures as the tree ages. Its leaves are heart-shaped and large, spiraling around the twigs. It produces multiple harvests of its fig-like fruit each year. Its widespread branches make it a familiar tree for association with travelers, shelter, and shade in desert regions.

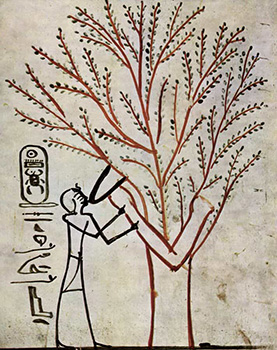

The sycamore was a sacred tree in Egypt, where its flourishing near the riverbank stood in contrast to the stark and empty desert. In ancient Egyptian mythology, the tree is associated with the Tree of Life and the goddess Hathor. Hathor was frequently depicted as a sycamore tree and called “Our Lady of the Sycamore.”

|

|

Ancient Egyptian Depiction of the Tree of Life and the Goddess Hathor.

|

The tree played a central role in the myth of Osiris and that culture’s story of death and resurrection. When Osiris was killed by his brother Set, Osiris’s body was hidden in a sycamore tree, awaiting resurrection.

The Philistines likely brought the tree to the Jordan Valley and to Jericho in the Iron Age (c.1200–550 BCE), where it became widespread. The sycamore tree appears seven times in the Hebrew scriptures. Most of the references compare it to the cedars of Lebanon, as in 1 Kings 10:27, where the passage discusses all the riches of Solomon who made “cedar as plentiful as sycamore trees.”

In other words, the sycamore was a plentiful tree with an ordinary abundance. It flourished where other trees would not. It wasn’t a tree of luxury, but was a humbler tree, whose porous wood was good for making coffins, and whose plentiful fruit was a staple for people who didn’t always have enough to eat.

These days there are few ficus sycomorus in Egypt because the symbiotic wasp that was essential to the flourishing of the tree is now extinct. There are still sycamores in the Jordan Valley. The tree is sacred in Kenya and in other African countries, where it too is associated with origin stories about the relationship between the divine and the human and the meaning of human flourishing.

So what difference does it make that Zacchaeus climbs a sycamore tree in his quest to see Jesus? How would the story resonate differently if he’d climbed a mulberry tree or an acacia? A cypress or a cedar? What would that sycamore tree specifically have said to the story’s original listeners?

|

|

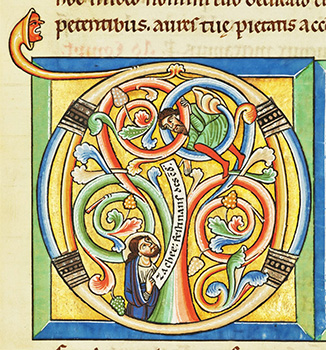

Initial D Containing the Encounter Between Jesus and Zacchaeus. From the Stammheim Missal (c.1170). |

Biblical scholar Amy Balogh writes that because we no longer speak the mythological language of trees, we miss their “constellations of meaning” in ancient texts. But ancient people had sacred trees “embedded in a millennia-long tradition of iconographic language and activity.”

In ancient mythology, trees often speak to the sacred feminine and answer questions like “Where did we come from?” and “Why are we the way we are?” They connect people to both earthly and heavenly realms, reminding people that all of life is interconnected.

Mircea Eliade wrote that trees in mythology represent “the living cosmos, endlessly renewing itself.” The tree is the center of the world and provides communication between divine and human life. “At the heart of the universe,” he wrote, “there is always a tree of eternal life or knowledge.”

In this story, the sycamore tree serves as a vehicle of understanding between the divine and the human. As Zacchaeus climbs the tree, he initiates his own transformation and perhaps re-establishes his ability to be in communication with the divine. Because it is a sycamore tree that he climbs, ancient readers might have understood that questions of value, generosity, flourishing, and abundance are at stake.

The tree is a symbol of the divine economy, and the passage uses the tree to hearken back to Solomon and Solomon’s wealth. The tree is a clue that we are to be looking, not for material wealth, but for a different kind of abundance, a spiritual abundance.

But the tree stands in contrast to the surrounding environment, which is under severe economic strain. During Jesus’ time, the Roman government was levying onerous taxes on the people of the Levant.

People were starving, not because they couldn’t grow enough to sustain themselves, but because Rome was taking so much of the land’s abundance for itself that there was not enough for the people to live on.

Ethnobotanist Gary Nabhan writes in Jesus for Fishers and Farmers that “the Roman Empire worked to extract every calorie of food, wine, or oil it could squeeze out of the land and sea. It endeavored to grab every coin out of the purses of every peasant there.”

|

|

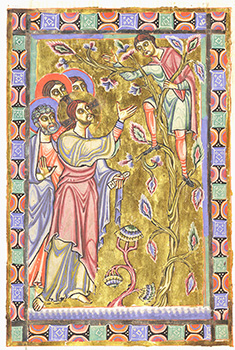

Jesus Encounters Zacchaeus. From the Book of Pericopes of the Monastery of Saint Erentrud (1140).

|

It helps me to remember that both Zacchaeus and the crowd who grumbles about Jesus calling out to Zacchaeus are both likely feeling the heavy weight of not having enough. The people from whom Zacchaeus is taking money are literally hungry, but Zacchaeus is hungry too, and it is directly to this other hunger — a spiritual hunger, but still a deeply human one — that Jesus speaks.

Jesus notes the gifts that Zacchaeus already has, the abundance that he already possesses: “Hurry and come down, for I must stay at your house today” (Luke 19:5). These simple words do two things simultaneously: they call Zacchaeus’s attention to his own gifts, and they say, in the words of 20th century theologian Paul Tillich, “You are accepted.”

“To be in sin,” Tillich says in his famous sermon by the same title, “is to be in a state of separation.” Whatever else sin might mean, this does seem to be what the crowd indicates when they grumble about Jesus going to the house of “one who is a sinner.” He is not one of us. He has separated himself and made himself unworthy. Through sin, “the walls of estrangement between heart and heart,” Tillich writes, “have been incredibly strengthened.”

The sycamore tree contradicts this sense of separation. Within ourselves there is still a longing for wholeness, a longing for that separation to be overcome, a longing for an ancient grace and healing that pilgrims to The Tree of the Virgin still come to seek. The branches, the fruit, and the natural abundance of the sycamore tell us that we are all connected to the Tree of Life. Like Zacchaeus, we can go to the tree to be reconnected.

Weekly Prayer

Mary Oliver (1935-2019)

It doesn’t have to be

the blue iris, it could be

weeds in a vacant lot, or a few

small stones; just

pay attention, then patcha few words together and don’t try

to make them elaborate, this isn’t

a contest but the doorwayinto thanks, and a silence in which

another voice may speak.Mary Oliver (1935–2019) was an American poet who won numerous prizes including the National Book Award and a Pulitzer Prize for poetry. This poem is from her book Thirst (Beacon, 2007).

Amy Frykholm: amy@journeywithjesus.net

Image credits: (1) HistoricalEve.com; (2, 3) Ad Imaginem Dei.