For Sunday September 4, 2022

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year C)

Jeremiah 4:11-12, 22-28 or Exodus 32:7-14

Psalm 14 or Psalm 51:1-11

1 Timothy 1:12-17

Luke 15:1-10

From Our Archives

Debie Thomas, "On Lostness" (2019); Dan Clendenin, "A Trustworthy Saying" (2016) and "Aelwyd a Gymhell: What I Learned in Wales this Summer" (2013).

Michael Fitzpatrick is a parishioner at St. Mark's Episcopal Church in Palo Alto, CA. After growing up in the rural northwest, he served over five years in the U. S. Army as a Chaplain's Assistant, including two deployments to Iraq. After completing his military service, Michael has done graduate work in literature and philosophy. He is now finishing his PhD at Stanford University.

Our text for this lectionary essay will be Exodus 32.7-14, for those of us on track 2 of the lectionary. I love this passage because it brings to the fore one of the many intentional paradoxes that define our faith tradition. Just as we are the people who, paradoxically, affirm that Christ was both fully divine and fully human, so our Exodus text alludes to another paradox: the unchanging Lord whose mind is changed.

The context of this story is the infamous golden calf episode, immortalized in Cecil B. DeMille movies. After delivering the Hebrew slaves from captivity and bringing them to the holy mountain, wherein the law of God is given to Moses, Moses and Joshua discover the Hebrews back in camp carousing about an idol. So God passes judgment on the people, condemning them for betraying the freedom which was gifted to them. Sentence is passed that the Hebrews will be destroyed and instead a great nation will be made from Moses and his descendants alone. But Moses steps in between God and the people.

|

|

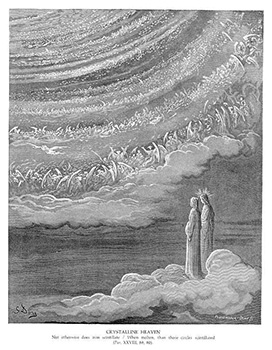

Crystalline Heaven by Gustave Dore.

|

Many well-meaning church leaders from my youth would often mis-appropriate Romans 9 in response to my young doubts, admonishing me, “Who are we to question the ways of God?” Yet I noticed even as a kid that quite a few major biblical figures do just that — they question the ways of God! Moses’ reply is not only bold but cunningly inventive in its argument. He not only recalls the covenant promise between Yahweh and the forebears, he also asks what salvation from slavery means if it just ends in the people being lost to corruption. However difficult the road to deliverance might be, it is not the road to deliverance unless lasting deliverance is achieved.

The text then says, almost nonchalantly, “And the Lord changed his mind about the disaster that he planned to bring on his people.”

What are we to make of this passage? It’s almost as if our Father in heaven lost his temper and set to wash his hands of us, before a motherly Moses brought the Father back to his senses. Of course, this is to read it through the lens of our patriarchal outbursts, as if God were like us. We cannot imagine what it is like to “be God.” We can at least erect signposts as we meditate on scripture that help us avoid ending up with an all too human portrait of God’s actions and responses.

As I mentioned above, this text brings to the fore a paradox of Christian faith: that God is both unchanging and changed. Historically, many church leaders have focused solely on the unchangingness of God, insisting that everything which happens is what God wills, and that we can do nothing to change the mind of God. St. Thomas Aquinas, commenting on passages like ours, writes, “These things are said of God in Scripture metaphorically.” He suggests that we pray or ask things of God not to change the Divine mind but because it is through our prayers the Lord acts. Aquinas’ suggestion is quite insightful, but it fails to do justice to the text before us. Moses is absolutely trying to change the divine mind! He is pleading with the divine justice to have mercy where mercy is undeserved!

In response, some theological communities such as process theology have rejected the notion that God doesn’t change, suggesting instead that God changes moment to moment just like we do. Thus the Deliverer of the Hebrews was learning how to be their God and was growing with them. Moses was helping God learn how to be more merciful by appealing to the best parts of God in dealing with the disobedient Hebrews.

|

|

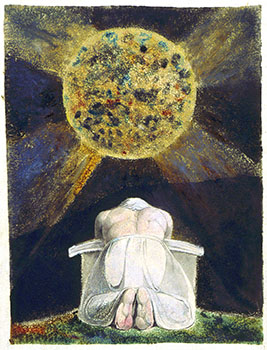

The Song of Los by William Blake.

|

There is another way to think about these scriptures, one that affirms that God is both unchanging and changing, though in different respects. The Danish Christian philosopher Søren Kierkegaard captures this in the prayer at the end of this essay. He describes God as

You Changeless One … You who are changeless in love, who just for our own good do not let yourself change.

We need an unchanging Creator because we need someone who will love us unconditionally, whose love will not change no matter how much we change. Yet we must not infer that God’s unchanging love is achieved by God being a static object, indifferent to and unaffected by our lives. As Kierkegaard goes on to pray,

But everything moves you, and in infinite love. Even what we human beings call a trifle and unmoved pass by, the sparrow’s need, that moves you; what we so often scarcely pay attention to, a human sigh, that moves you, Infinite Love.

As process philosopher C. Robert Mesle nicely puts it, “God is not an impartial, disinterested observer of the world but the uniquely omni-partial and totally interested participant in every relationship there is.” To say that God can be changed is not to suggest that God’s love for the world can be changed, but simply to say that there is no part of the world, no matter how meaningless to us, that is not of importance to God. In the essay his prayer is taken from, Kierkegaard writes,

For God nothing is significant and nothing is insignificant, that in one sense for him the significant is insignificant, and in another sense for him even the least insignificance is something infinitely significant.

Nothing is significant for God in that there is nothing we can do to make God stop being the person that God is. We cannot coerce the Lover of our souls into doing what we want; we cannot hold creation ransom to blackmail our Maker. Our Creator will always be, regardless. And yet because God will always be, regardless, God is therefore free to care about everything, every dust mote and blade of grass, because the Creator of all things needs nothing and therefore can be for everything else. The smallest particle in the farthest reaches of the cosmos is no further away from its Maker than you or me.

Nor does God being the Changeless One mean that our distance from God is determined only by whether we draw near or move away, as Aquinas sometimes regretfully implies. Kierkegaard insists that God’s nearness lies in the changelessness of God, because, speaking of God,

You . . . are not only like a spring that lets itself be found — what a poor description of your being! — you … are like a spring that even searches for the thirsting, the straying, something unheard of about any spring. Thus are you unchanged and everywhere to be found.

|

|

The Mississippi River by Anna King.

|

How does this help us understand Moses challenging God to not pass judgment on the Hebrews? Far from a “losing of one’s cool,” the Deliverer of the Hebrews condemns the longing of freed slaves for renewed slavery. If they will throw off the promises of God, then those promises will fall to those who would have them. The Lord is describing their changefulness, not his own.

Because the Lord is unchanging, Moses is confident that he can appeal to the same unchanging faithfulness that judges the Hebrews to also have mercy. Moses reflects back to God what God has already demonstrated towards all the Hebrews: the posture of the advocate. Just as the Redeemer advocated for the people before Pharaoh, so now Moses advocates for the people before their Redeemer. The Lord’s mind is changed because God is the unchanging spring that searches for the thirsting and the straying. The Lord’s mind is changed because the unchanging God is the one who is moved by everything and everyone, for nothing is so insignificant to not be of importance to its Maker.

We need a God whose love and justice and mercy will always be faithful, for as Kierkegaard writes, only in such permanence that we can find true peace: “My home is eternally safeguarded; I rest in God’s changelessness.” Yet because this is who God is and unchangingly so, we can be assured that this is the God who cares infinitely for us and is totally moved by our lives. “No one strays so far away that he cannot find his way back to you,” Kierkegaard adds in hopeful praise. Just as Moses advocated for a deeply sinful people trusting that God would be moved, we too can advocate before the God who keeps promises to keep those promises even when we have failed to keep ours.

Note: The Kierkegaard essay is cited below. The C. Robert Mesle quote is taken from his book Process-Relational Philosophy. St. Thomas Aquinas quotes are from the Summa Theologiae.

Weekly Prayer

Søren Kierkegaard (1813–1855)

You Changeless One, whom nothing changes

You Changeless One, whom nothing changes! You who are

changeless in love, who just for our own good do not let yourself

change-would that we also might will our own well-being, let

ourselves be brought up, in unconditional obedience, by your

changelessness to find rest and to rest in your changelessness! You

are not like a human being. If he is to maintain a mere measure

of changelessness, he must not have too much that can move him

and must not let himself be moved too much. But everything

moves you, and in infinite love. Even what we human beings call

a trifle and unmoved pass by, the sparrow's need, that moves

you; what we so often scarcely pay attention to, a human sigh,

that moves you, Infinite Love. But nothing changes you, you

Changeless One! O you who in infinite love let yourself be

moved, may this our prayer also move you to bless it so that the

prayer may change the one who is praying into conformity with

your changeless will, you Changeless One!Søren Kierkegaard was a Danish philosopher whose meditations, journals, and sermons were catalysts for the Christian existentialist movement. This prayer is taken from the introduction to his essay, "The Changelessness of God," found in the collection of Kierkegaard writings, The Moment and Late Writings, eds. Howard V. Hong and Edna H. Hong, Princeton University Press, 1998, p. 268.

Michael Fitzpatrick welcomes comments and questions via m.c.fitzpatrick@outlook.com

Image credits: (1) WikiArt Visual Art Encyclopedia; (2) The William Blake Archive; and (3) Wikimedia.org.