From Our Archives

Debie Thomas, "By Your Endurance" (2019); Dan Clendenin, "Come By Here: America's Presidential Election" (2016); and "Don't Grow Tired of Doing Good" (2013).

For Sunday November 13, 2022

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year C)

Isaiah 65:17-25 or Malachi 4:1-2a

Canticle 9 or Psalm 98

2 Thessalonians 3:6-13

Luke 21:5-19

This Week's Essay

Michael Fitzpatrick is a parishioner at St. Mark's Episcopal Church in Palo Alto, CA. After growing up in the rural northwest, he served over five years in the U. S. Army as a Chaplain's Assistant, including two deployments to Iraq. After completing his military service, Michael has done graduate work in literature and philosophy. He is now finishing his PhD at Stanford University.

“They live on government handouts. That means their parents don’t want to work. They’re really lazy.”

I absorbed that sincere counsel from my schoolmates throughout my primary education. My Sunday school teacher explained one Sunday morning that we have to earn the means of our survival by our hard work, so that we can be self-reliant and provide for our needs and not depend on others. Then, with an impressive flourish of wisdom, he opened his Bible to 2 Thessalonians 3.10 and read, “If anyone will not work, neither shall he eat” (NKJV).

Thank the Lord that hardly closed the door on my inquisitive mind! As I went through my high school years, I kept stumbling over verses like Jesus’ parable in Luke 19 about the master who reaps what he did not sow by letting his money accumulate interest. He didn’t do the work, but he still received the benefit! Or the suggestive thread throughout the Acts and the epistles about St. Paul leading an organized collection of money for the most vulnerable in Jerusalem. Was Paul really saying to them that if they won’t work, they can’t eat?

|

|

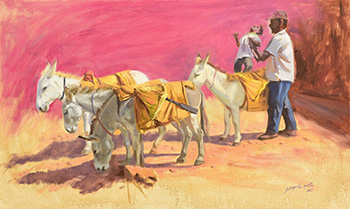

Honest Work painting by Indian artist Swapnil Patil, 2017.

|

The historical legacy of this Bible verse includes opposing social aid to the unemployed or the impoverished. In the U.K. in 1834, a law was passed restricting social relief for the poor and unemployed to only those in workhouses, truly awful environments set aside for those who couldn’t find work elsewhere. Those who ventured inside a workhouse would receive a small pittance in exchange for grueling labor. The law replaced the older English practice of “outdoor relief,” in which people could receive food, warm blankets, and clothing, all without strings attached. The newer policy of “indoor relief” required those receiving public support to work in exchange for benefits. Social reformer Jeremy Bentham argued in favor of the Poor Law of 1834 by suggesting that human nature is such that we will do what is pleasant and not what is unpleasant. Since work is unpleasant and getting unconditional poverty relief is pleasant, the only way to discourage people from being lazy and living on free poverty relief is to make it conditional on grueling work. Such a policy, Bentham thought, would incentivize people to work hard to earn enough to avoid the workhouses. If you do not work, you do not eat.

Nor is this principle unique to the history of liberal democracies. The same principle underwrote state communism in the 20th century. In his book The State and Revolution, Vladimir Lenin contends that “he who does not work shall not eat” is a fundamental principle of socialism. The difference of course is that, unlike the Whigs in the United Kingdom who aimed the principle at the poor, Lenin aimed it at the wealthy! Lenin and Stalin believed that it was the rich who eat without work, letting the poor do their work for them and then reaping all the benefits. Unfortunately, in practice the communists applied this principle to the poor far more than the rich. During the Soviet famine of the Great Depression, the U. S. S. R forced its outlying territories such as Ukraine to produce food that was then exported to other parts of the Soviet Union as “evidence” that their collective production system was surviving the Great Depression better than the free markets of liberal democracy. Yet Ukrainians were unable to keep up with the unrealistic demands Stalin made for grain production, and were punished by having much of their own food confiscated. The Ukrainians did the work while the Russians claimed it for ulterior purposes. More than 3 million Ukrainians died from starvation as a result.

The principle persists today. In the 1990's, the Clinton administration and Republicans in control of Congress passed the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Act of 1996 (a revealing name) to re-assert “America’s work ethic” and to fulfill President Clinton’s promise to “end welfare as we know it.” The act added significant “workfare” conditions to social relief programs. Recipients had to resume work within a period of time, and lifetime benefits were capped. Even today unemployment benefits or other forms of support are often granted conditionally on seeking employment or going through occupational re-training. Over the decade after the ‘96 act was passed, welfare claimants indeed dropped, precipitously even, but the number of people in poverty rose just as drastically, especially in minority communities. It also perpetuated the image of “welfare queens” as lazy, negligent black single mothers who don’t care for their children and therefore shouldn’t get social relief until they get a job (while still caring for their kids!).

|

|

An Honest Day's Work painting by Uzbekistan artist Csilla Florida, 2014.

|

Workfare policies impacted me in a personal way during the pandemic. I was laid off from teaching, and the only work I had was writing here for JwJ. When I applied for unemployment insurance from the State of California, they refused to count my JwJ wages as part of my total earned income. As an independent contractor, my sort of work is excluded from benefits, presumably to encourage me to get “a real job.” Worse, while they would not count my JwJ wages as part of my earned income in the past, they would count them against how much I should be allotted in unemployment compensation! California double-counted my income against me, whittling my compensation twice over. Apparently the adage should be, “Those who don’t do the approved kind of work, don’t eat!”

Is St. Paul really setting down a rule that has been followed by conservatives, liberals, and communists alike? It’s worth noting first that St. Paul’s diction is precise — “Anyone unwilling to work,” not those who don’t work. His focus is on the motivation of the heart. But what does he have in mind by work? Forming a startup or achieving a big stock market IPO? The end of the passage marks out Paul’s aim: “As for you, sisters and brothers, never tire of doing what is good.”

St. Paul makes a distinction between the busy and busybodies. The busy are those who focus on doing good and earn the food they eat. Busybodies, on the other hand, are idle and disruptive and take from others without giving anything in return. Paul and the other apostles did not set an example of being busybodies; “on the contrary, we worked night and day, laboring and toiling so that we would not be a burden to any of you.” It is to avoid being a burden to others that those unwilling to work should not eat.

What kind of burden does Paul have in mind? The burden of a sick loved one who requires 24hr care? The burden of the disabled who require reasonable access to buildings and employment? No, for these “burdens” are not burdens at all in the eyes of Paul, who is eager to remember the needy and do everything possible to help them (Gal. 2.10). Rather, being a burden in the context of this passage is exploiting your community. In Paul’s ecclesiology, every person has been called by God for a communal purpose. It is the purpose of all to be a servant of each, according to the gifts the Holy Spirit has given us. Paul’s picture of community is one of maximum dependency, where no one is self-sufficient but all depend on others doing good. When someone receives the goods of the community without giving back, they are not living in accordance with the Christian practice of mutual self-giving and sacrifice.

St. Paul is saying that to truly follow Christ, one cannot exist in a way as to simply take advantage of others. To follow Christ is to work; that is, to never tire of doing good. Paul is not saying that if someone does not work, let them starve to death! He’s not instructing us to withhold care from the homeless, the poor, or the outcast because they didn’t do their fair share. That would be contrary to instructions in the epistle of James that if a sister or brother is without clothes and daily food, we must address their physical needs without expectation of return (James 2.15-16). After all, “doing good” for Paul is not seeking gain for ourselves, but the good of others (1 Cor. 10.24).

|

|

Court Ladies Preparing Newly Woven Silk painting by ancient Chinese artist Zhang Xuan, 713-755 A. D.

|

Far from being a prohibition against helping those in need if they can’t or won’t work, St. Paul’s wants those who can to work so that they have something to give those in need. In another letter Paul writes, “Anyone who has been stealing must steal no longer, but must work, doing something useful with their own hands, that they may have something to share with those in need” (Eph. 4.28). We perform useful labor with our own hands to generate goods so that we have something to share. He reiterates this again in the letter to Titus: “Our people must learn to devote themselves to doing what is good, in order to provide for urgent needs and not live unproductive lives” (3.14). An “unproductive life” is one where we are unable to provide for the needs of others because we have not devoted ourselves to doing what is good.

Saying that those who are unwilling to work should not eat means that those who do not devote themselves to doing good should not be able to take advantage of a church’s commitment to help those in need. Doing so takes from those who are in need when we ourselves are not. Paul is not talking about widows or the poor or “welfare queens,” for he doesn’t see them as lazy and unwilling to work — they are the exploited his principle is meant to protect! Rather, Paul is speaking to those who want to enjoy the benefits of the fellowship of Christ without having to take responsibility for serving others. And that is simply to not follow Christ.

For further reflection on the Christian meaning of work, I encourage readers to check out my 8th Day essay "Leisure".

Weekly Prayer

Wendell Berry (born 1934)It may be that when we no longer know what to do

we have come to our real work,and that when we no longer know which way to go

we have come to our real journey.

The mind that is not baffled is not employed.

The impeded stream is the one that sings.Poet, essayist, farmer, and novelist Wendell Berry was born on August 5, 1934, in Newcastle, Kentucky. He attended the University of Kentucky at Lexington where he received a B.A. in English in 1956 and an M.A. in 1957. Berry is the author of more than thirty books of poetry, essays, and novels. He has taught at New York University and at the University of Kentucky. Among his honors and awards are fellowships from the Guggenheim and Rockefeller Foundations, a Lannan Foundation Award, and a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts. He married Tanya Amyx in 1957; they have two children. Wendell Berry lives on a farm in Port Royal, Kentucky. From http://www.poets.org/poet.php/prmPID/675.

Michael Fitzpatrick welcomes comments and questions via m.c.fitzpatrick@outlook.com

Image credits: (1) Pinimg.com; (2) Fine Art America; and (3) Shine.cn .