From Our Archives

Debie Thomas, On Fairness (2020); and A Troubling Generosity (2017).

For Sunday September 24, 2023

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year A)

Exodus 16:2–15 or Jonah 3:10–4:11

Psalm 105:1–6, 37–45 or Psalm 145:1–8

Philippians 1:21–30

Matthew 20:1–16

This Week's Essay

For those of us who profess to care for the poor, I'm sure you've had an experience similar to mine. There's a farmer's market near my house where a disheveled man parks his wheelchair very strategically at the entrance to the store. His puffy face is bright red. His legs are badly swollen.

As soon as I get out of my car, I can see this man, so there's plenty of time for the many voices inside my head to debate whether to give him any money. Won't he spend it on booze? How will my single dollar help? Will I have to do this every time I shop here? It feels so manipulative.

Sometimes I give him a dollar. But that feels embarrassingly stingy, so one time I gave him five dollars. Another time, my smallest bill was a twenty. Should I give him twenty dollars? Isn't that excessive?

Part of my problem was that I had recently read through the four gospels, and one of the things I noticed was the exaggerated language that's repeatedly used to describe the generosity of God, life in God's kingdom, and our human responses to God's generosity. Most of us live in a socioeconomic meritocracy where "you get what you deserve," and you "earn your own way." In many ways we are truly bound by such constraints. But in God's upside-down kingdom, we get what we don't deserve and what we didn't earn.

|

|

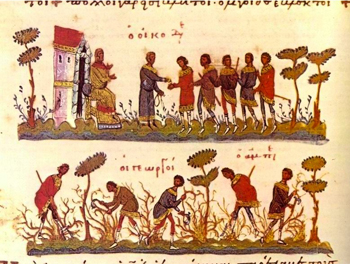

Parable of the workers in the vineyard, 11th-century Byzantine.

|

The British literary critic Frank Kermode (1919–2010) called this exaggerated language in the gospels a "rhetoric of excess." The gospel of Matthew for this week in particular has what he calls a "quite unusual intensity" of rhetorical excess. Matthew talks about about a log in your eye, a camel squeezing through the eye of a needle, and straining a gnat while swallowing a camel.

Matthew says that "our righteousness must be produced to excess," observes Kermode, it must exceed that of the Pharisees. We must love not only our neighbors but also our enemies. We should give in secret, so that our left hand doesn't know what our right hand is doing—that is, hidden even from our own selves. When we pray, we should hide ourselves inside a closet with the door shut and pray secretly. Wise people leave their dead unburied. Foolish people build houses on sand and walk through wide gates. Kermode thus writes, "Excess is constantly demanded. Everything must be in excess."

Another example of excess that Kermode gives is the gospel this week about the workers in the vineyard. It's a story about a business owner with crazy ideas about a fair wage. The punch line of the story shocked the listeners with a radical reversal that subverted conventional wisdom. And to make Jesus's teaching clear, Matthew repeats the punch line verbatim three times. He says that in God's kingdom, the first will be last and the last will be first.

The parable of the workers is preceded by a story about a rich man. When Jesus invited the man to sell his possessions and give his money to the poor, "he went away sad, because he had great wealth."

Peter then responded, "Lord, we have left everything to follow you. What then will there be for us?" The rich man kept all that he had; the disciples left all that they had. Jesus reassured them: "At the renewal of all things, many who are first will be last, and many who are last will be first."

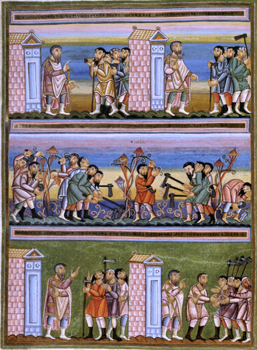

Jesus follows this with a story about a foreman who hired some laborers early in the morning, then additional workers at the third, sixth, ninth, and eleventh hours. That evening, he paid the workers, "beginning with the last ones hired and going on to the first."

Whereas the first workers hired had endured "the burden of the work and the heat of the day" for twelve hours, the last workers hired at the eleventh hour worked just one hour. Even worse, they had otherwise "stood there all day long doing nothing." Nonetheless, the last people hired received twelve hours of pay for one hour of work.

The laborers who had worked twelve hours "grumbled against the landowner." Of course they grumbled! It wasn't fair, not by a long shot. But the excessive generosity of God is different than getting what you earned. And so for the third time Jesus says, "the last will be first, and the first will be last."

Jesus concludes with a sharp question to those who grumbled about God's excess: "Are you envious because I am generous?"

|

|

Parable of the workers in the vineyard, 11th-century codex.

|

The alternate reading from Jonah this week makes this same point. When God had compassion on the pagan Ninevites, Jonah complained bitterly in words that echo the grumblers in Jesus's parable: "I knew that you were a gracious and compassionate God, slow to anger and abounding in love, a God who relents from sending calamity."

When Jonah finally preached to Israel's enemy conquerors, the unthinkable happened. The city that was famous for its cruelty and wickedness believed the message and repented. The king proclaimed a national day of civic repentance.

Jonah couldn't imagine that pagan Nineveh was a city “important to God” (3:3), and a city for which God had great compassion (3:10). And just as Jesus asked the grumblers a question, so God asked Jonah a question in the very last sentence of this story: "Should I not have compassion on that great city?" (4:10).

The "rhetoric of excess" isn't limited to Matthew, which was Kermode's focus. You find it everywhere in the gospels. Some times this excess is rightly interpreted figuratively, other times it was taken quite literally by Jesus's followers, and still other times it's hard to know what to do. The church father Origen (185–253) was said to have castrated himself out of obedience to Matthew 19:12.

The gospel for last week provides another example. Jesus told us to forgive a person 490 times — "seventy times seven." Divine forgiveness, given and received, is beyond calculation or comprehension. Forgiveness on that scale is wildly disproportionate to the sincerity of the penitent or the seriousness of their offense.

Some disciples quit their jobs.

Others left their families, like the rich women who itinerated with Jesus and supported him.

One woman, instead of helping the poor, anointed Jesus with perfume that was worth a year's wages.

Luke compares God to a shepherd who abandons a flock of ninety-nine sheep in order to find one lost sheep. In the parable of the prodigal son he's like an indulgent father who welcomes back his indigent son with the best party that money could buy, despite the understandable anger of the older son at such excessive generosity.

John compares God's kingdom to a wedding party with an outrageous excess of expensive wine. He says that the whole world couldn't contain enough books to describe the deeds of Jesus.

In the book of Acts, some people sold property and distributed the proceeds to the Jesus movement.

Yes, I gave the man at the market my twenty dollar bill. It was an honest and impulsive effort to imitate the excessive generosity of God by doing something that defied common sense or conventional wisdom. It felt good, too.

The irony is that, compared to the gospel's rhetoric of excess, my twenty dollars was at best a pale imitation of the generosity of God. You could even say that it was more parsimonious than profligate. I gave out of the surplus of my wealth. I recall a widow described by Jesus who despite her extreme poverty "gave everything she had to live on."

* See Frank Kermode, "Matthew," in Robert Alter and Frank Kermode, eds., A Literary Guide to the Bible (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1987), pp. 378–401.

Weekly Prayer

Allison Funk

The Prodigal’s Mother Speaks to God

When he returned a second time,

the straps of his sandals broken,

his robe stained with wine,it was not as easy to forgive.

By then his father

was long gone himself,leaving me with my other son, the sullen one

whose anger is the instrument he tunes

from good morning on.I know.

There’s no room for a man

in the womb.But when I saw my youngest coming from far off,

so small he seemed, a kid

unsteady on its legs.She-goat

what will you do? I thought,

remembering when he learned to walk.Shape shifter! It’s like looking through water—

the heat bends, it blurs everything: brush, precipice.A shambles between us.

Allison Funk is a poet and Professor Emerita at Southern Illinois University at Edwardsville. Her latest book of poems is Wonder Rooms from Parlor Press (2015). She has published four other books of poems: The Tumbling Box (C&R Press, 2009); The Knot Garden (Sheep Meadow Press, 2002); Living at the Epicenter (Northeastern University Press, 1995); and Forms of Conversion (Alice James Books, 1986). She has received a fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts and prizes from the Illinois Arts Council and the Poetry Society of America.

Dan Clendenin: dan@journeywithjesus.net

Image credits: (1) Roundchurch.ca and (2) Marysrosaries.com.