For Sunday September 20, 2020

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year A)

Jonah 3:10-4:11

Psalm 145:1-8

Phillippians 1:21-30

Matthew 20:1-16

A few years ago, Sarah Brosnan and Frans de Waal, two zoologists at Emory University, decided to study the evolution of fairness. They wanted to explore where our distaste for unfairness comes from. Is it a cultural add-on, or is it hardwired?

To study this question, Brosnan and de Waal designed an experiment using capuchin monkeys. Pairs of monkeys were placed in adjacent cages where they could see each other, and trained to take turns giving small granite rocks to their human handler. Each time a monkey relinquished a rock, she would receive a piece of cucumber as a reward.

Capuchins love cucumbers, so both monkeys found this arrangement satisfactory, and handed over their rocks with enthusiasm. But then, the handler changed things up. After a few fair and even exchanges, the handler rewarded the first monkey with a chunk of cucumber as usual, but gave the second monkey a grape — the equivalent of fine wine or caviar in the monkey world.

Seeing that the game had changed for the better, the first monkey perked up, and very eagerly handed over another rock, expecting, of course, to receive a grape, too. But no — the handler gave her another piece of cucumber. To make things worse, the handler then gave the second monkey another grape for free!

The results — which you can look up on YouTube — were striking. The first monkey just about lost her mind. Not only did she refuse to eat the cucumber; she hurled it at the handler’s face. She then proceeded to bang against the bars of the cage, throw her remaining rocks in every direction, and make furious gestures at her grape-eating companion.

The experiment has since been repeated using other primates, and the results have been astonishingly similar. Scientists have also studied the development of fairness in human babies, and found that infants as young as nine months old will react quite strongly and negatively to perceived unfairness. Clearly, as Brosnan and De Waal concluded after their experiment, fairness is a concept that is deeply rooted in the human psyche.

|

Which brings us to this week's lectionary, which features two stories about fairness that might very well lead us to behave like that first capuchin monkey, and throw a few cucumbers at God. Why? Because both stories turn our hardwired assumptions on their heads, and challenge us to consider tough questions about fairness, justice, and equality that we’d rather ignore. In his 1993 book, Wishful Thinking: A Seeker's ABC, Frederick Buechner offers this advice about reading Scripture: "Don't start looking in the Bible for the answers it gives. Start by listening for the questions it asks.” When you hear the question that is your question, you have begun your journey.

Two questions lie at the heart of today’s readings. Neither is easy or comfortable, but if we allow them to become our own, they might have something to teach us about ourselves, and about God.

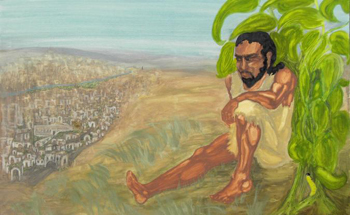

The first question comes from the Book of Jonah, named for the reluctant protagonist of this week’s Old Testament reading. Following his precarious adventure in the belly of a whale, Jonah has obeyed God’s instructions and warned the people of Nineveh about their wickedness. But in a stunning turn of events, the Ninevites have taken Jonah’s warning to heart and repented. God, seeing their penitence, has changed God’s mind and shown them mercy.

In other words, Jonah has preached a sermon, and his congregation has actually listened and responded to it! It’s every priest’s dream, and you'd think that Jonah would be thrilled. But no — he’s not. He’s furious, and he tells God so in the most animated language he can think of. “I’m so angry, I’d rather die than live.” He then hunkers down east of the city, hoping God will change God’s mind again and burn Nineveh to the ground.

Instead, God offers Jonah an object lesson using a weed, a worm, and the wind — and concludes the lesson with a zinger of a question: “Is it right for you to be angry?”

The question is a fraught one, given the context, because Nineveh isn’t just any old city. It is the capital city of Assyria, Israel’s bitter enemy. Notorious throughout the ancient Near East for its violence and depravity, Assyria is the empire that will eventually obliterate the northern kingdom of Israel. To Jonah, then, God’s question is a ridiculous one. Of course he has a right to be angry. Isn’t it right to be angry that God’s mercy extends to killers? Isn’t it right to be angry when people who break the rules don’t get the comeuppance they deserve? Isn’t it right to be angry that God’s grace is so reckless and wasteful, it challenges our most cherished assumptions about justice?

One thing I love about this story is that God doesn’t scold Jonah for his anger. Instead, God playfully attempts to broaden Jonah’s horizons, in the hopes that the grumpy preacher will eventually learn to see the Ninevites as God sees them. For while the Assyrians are everything Jonah believes them to be — while they are violent, depraved, and wicked — they are also more. They are a “great city,” God says, but they “don’t know their right hand from their left.” In other words, they’re human beings made in God’s image, but they’re lost and broken. What they deserve is neither here nor there. What they need is compassion.

Theologian and mystic Richard Rohr argues that while many people nowadays associate the word “justice” with retribution and the penal system, Jesus and the prophets clearly practiced something else. Something we’d now call "restorative justice." “Jesus never punished anybody,” Rohr writes. “He undercut the basis for all violent, exclusionary, and punitive behavior. He became the forgiving victim so we would stop creating victims…. Punishment relies on enforcement and compliance but it does not change the soul or the heart. Jesus always held out for the heart.”

God challenges Jonah to consider the hard truth that even his worst enemies are God’s beloved children. Just as the whale, the weed, the worm, and the wind in Jonah’s story belong to God, so do the Assyrians themselves. They are ultimately God’s creations — God’s to plant, God’s to tend, and God’s to uproot. Should God not care for God’s own? Is it right for Jonah to be angry?

|

The story wisely ends with these questions unanswered. We’re left with Jonah still sulking like the capuchin monkey in the cucumber experiment, sitting outside the city and waiting to see what will happen to the people he hates and God loves.

And so we, too, are left to wrestle with the scandalous goodness of God, a goodness that calls us to become instruments of grace even to those who offend us most deeply. A goodness that asks why we so often prefer vindication to rehabilitation — prison cells and death sentences to hospitality and compassion. A goodness that exposes our smallness and stinginess, our reluctance to embrace the radical, universal kinship God calls us to embrace. A goodness that reminds us how often we grab at the second chances God gives us, even as we deny those second chances to others. A goodness that dares us to do the braver and riskier thing — to hold out for the hearts of those who belong to God, whether we like them or not.

Do we have a right to be angry? God leaves us to decide.

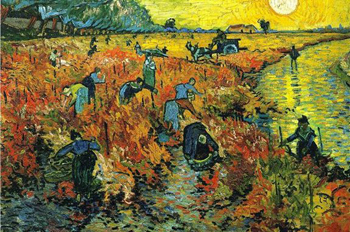

The second and related question comes from this week's New Testament reading. In "The Parable of the Generous Landowner,” a landowner goes out several times in the course of a day to hire laborers for his vineyard. When the long workday is at last over, the landowner pays every worker the exact same wage, and the laborers who started work at the crack of dawn complain. In response, the landowner deflects their accusations with a question similar to God’s question to Jonah: “Am I not allowed to do what I choose with what belongs to me? Or are you envious because I am generous?”

Writer Mary Gordon, in her book Reading Jesus, answers God’s question with painful honesty. She says yes. Yes, “I am envious because you are generous. I am envious because my work has not been rewarded. I am envious because someone has gotten away with something. Envy has eaten out my heart.”

I appreciate Gordon’s candor, because really, if this parable doesn’t offend us at least a little bit, then we’re not paying attention. After all, we know what fairness is, and we know how it’s supposed to play out. Equal pay for equal work is fair. Equal pay for unequal work is NOT fair. Having our sincere efforts noticed and praised is fair. Having them ignored is NOT fair. Rewarding hard work and ambition is fair. Excusing sloth and sloppiness is NOT fair.

Here in Silicon Valley where I live, a stressed and high-strung culture teaches children and teens that the only place in the world worth standing is at the front of whatever line they happen to be in. Academic, musical, athletic, pre-professional. Why be second when you can be first? Why be mediocre when genius is what pays? Why bother with your neighbor’s needs when resources are scarce and time is flying? Work hard. Work harder. Work harder still. Happiness comes to those who slog the longest to achieve the highest success. Because that’s how the world works. That’s how fairness works.

But God — if the landowner in Jesus’s parable represents God — is not fair. At least, not according to our inherited beliefs about fairness. God, it turns out, does not believe that the best place to be is at the front of the line. God isn’t interested, as we so often are, in showing favor to the best, the biggest, and the brightest — the workers with the most elite educations, astonishing professional achievements, and fanciest zip codes.

In fact, the landowner in Jesus’s story doesn’t judge his workers by their hours. He doesn't obsess over why some workers are able to start at dawn and others are not. Perhaps the late starters aren’t as literate, educated, or skilled as their competitors. Perhaps they have learning challenges, or a tough home life, or children to care for at home. Perhaps they’re refugees, or don’t own cars, or don’t speak the language, or can’t get greencards. Perhaps they struggle with chronic depression or anxiety. Perhaps they've hit a glass ceiling after years of effort, and they're stuck. Perhaps employers refuse to hire them because they’re gay, or trans, or disabled, or black, or female.

Whatever the case may be, the landowner doesn’t ask them to explain or defend themselves. All he cares about is that every last person in the marketplace finds a spot in his vineyard — the early bird and the latecomer, the able-bodied and the infirm, the young and the old, the popular and the forgotten. When the workday is over, what concerns the landowner is not who deserves what. All he cares about is that every worker ends the day with the dignity and security of a living wage. The capacity to go home and feed a family. Sufficient security and peace of mind to sleep well. A solid grasp on hope. A reliable sense of accomplishment, belonging, and dignity.

“Are you envious because I am generous?” asks God. Or literally, in the Greek: “Is your eye evil because I am good?”

|

It embarrasses me to admit this, but ever since I was a little girl, I have always assumed, when hearing or reading this parable, that I would have been one of the 6:00am workers in the landowner’s vineyard. Of course I’d be first in line and ready to go before the sun came up. Of course I’d work the hardest and the longest. I’m Type A! I’m a morning person! I’m a “J” on the Myers-Briggs and a 6 on the Enneagram!

But consider this: the parable reads very differently if you situate yourself at the end of the line. The workers who got more than they expected to — the ones who received twelve times the pay they knew they deserved — they were ecstatic at the end of their workday. Ecstatic, stunned, thrilled, and grateful. Their experience was one of utter blessing, and I’ll bet that what went on at their end of the line was one big raucous party.

But all the other stuff? The envy? The bitterness? The grumbling? The dissatisfaction? All of that murky stuff belonged to the “deserving” folks at the front of the line. They couldn’t party — they were too busy feeling miffed and offended. They couldn’t take satisfaction in their hours of good work. They couldn't delight in the fruit of the vineyard. They couldn't relax into their time off and enjoy the gifts of leisure. Though the landowner honored his agreement with them, though they received their daily bread and lacked no good thing, they ended up wasting their off-hours in resentment and anger. Like the monkey in Brosnan and de Waal’s experiment, they took a perfectly good reward, and hurled it into the empty air, fists raised.

“Is your eye evil because I am good?” God asks. Maybe, if God’s generosity offends us, it’s because we don’t have eyes to see where we actually stand in the line of God’s grace and kindness. Where would we rather stand in the end? At the front of the line, where bitterness and judgment reign? Or at the back, where joy has won the day?

I don’t think it’s a coincidence that the landowner insists on paying his workers in reverse order, thereby making sure that the first workers see what the last receive. He wants them to experience what radical generosity looks like. He wants them to relinquish their anger and join the party. He wants them to use their plenty to build longer tables, not higher walls.

I'll be blunt: these two stories about fairness and justice are stories for us. Stories for right now. Stories for the times we live in. As I sit here writing this essay, the air outside my door is so polluted from the ongoing wildfires, it’s unsafe to leave the house. Human-caused climate change has done this. Meanwhile, Covid-19 is casting shadows of death, fear, hunger, unemployment, and misery all around the world, and many of our collective responses to the pandemic are intensifying the losses. People of color in the U.S and around the world are starving for equality and justice, and some of us are still refusing to honor and address their pain.

Could it be any more obvious that we — all of us, every single one of us — are wholly dependent on each other for our survival and well-being? That the future of Creation itself depends on human beings recognizing our fundamental interconnectedness, and acting in concert for the good of all? That what’s “fair” for me isn’t good enough if it leaves you in the darkness to die? That my sense of “justice” is not just if it mocks the tender, weeping heart of God? That the vineyards of this world thrive only when everyone — everyone — has a place of dignity and purpose within them? That the time for all selfish and stingy notions of fairness is over?

Are we willing to see this yet? Are we willing to live it?

Is it right for you to be angry? Are you envious because God is generous? Listen for the questions. When you hear the question that is your question, you have begun your journey.

Debie Thomas: debie.thomas1@gmail.com

Image credits: (1) Blogspot.com; (2) The Catholic World Report; and (3) Curious Christian.