From Our Archives

For earlier essays on this week's RCL texts, see Dan Clendenin, Beyond a Sentimental Gospel: The Slaughter of the Innocents (2010) and Pam Fickenscher, Remembering Rachel: The Slaughter of the Innocents (2007).

This Week's Essay

By Amy Frykholm, who writes the lectionary essay every week for JWJ.

Hebrews 2:10–18: “For it is clear that he did not come to help angels but the descendants of Abraham.”

For Sunday December 28, 2025

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year A)

Psalm 148

Hebrews 2:10–18

Matthew 2:13–23

When Mary Poole first saw the now famous photo of Alan Kurdi, a two year-old Syrian refugee, lying dead on a beach in Turkiye, everything changed. She still can’t talk about that day without crying.

Little Alan lies face down, in blue shorts and a red polo shirt. His head rests on a wave, as if on a pillow. He drowned on September 2, 2015. The photo, taken by Turkish journalist Nilüfer Demir, circulated rapidly around the world. Alan drowned along with his brother and his mother while the family was attempting a dangerous crossing from Turkiye to Greece on the Mediterranean Sea.

“There was something about that image,” Mary tells me. “It was eerily peaceful. . . . We’ve grown up in a time when we see images of war; they always have this violence to them, obviously, blood and broken bones. Buildings in rubble. But there was a very serene and peaceful quality to this scene that could have been a vacation on a beach. It was very haunting.”

Mary had never before felt called into action as she was then. She didn’t know anything about refugees or refugee resettlement. She in fact had never met a refugee. “I started calling and emailing anything with the name refugee in it.”

The day after Mary saw the photo, she brought it to a group of women that had been meeting to talk about investments and how their money was affecting global problems like war and climate change. That had morphed into a group discussing world events.

Within a year, they had founded an organization called Soft Landing Missoula. One of the first things Mary learned was that her own home state of Montana was, at the time, one of only two states that did not receive refugees. This was ten years ago, before two Trump Administrations dismantled most of the infrastructure that existed in the United States for resettling refugees. Soft Landing Missoula continues to work to create a “long welcome” for refugees in the state of Montana, creating the context for community, prosperity, and mutual understanding.

|

|

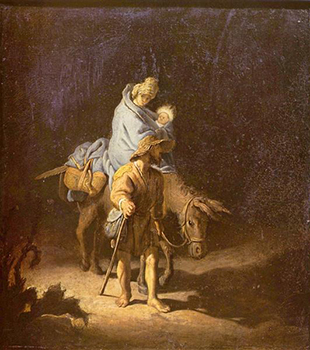

Rembrandt, The Flight into Egypt (1627).

|

One day I went to the Missoula apartment of Joel and Bikyeombe, originally from the Democratic Republic of Congo, who had spent almost their entire lives in a refugee camp in Tanzania. They had five children, some of whom were sitting at the dining room table eating plates of chicken and rice with their hands. On the otherwise bare wall were three images of Joel and Bikyeombe’s attempts to orient themselves in their new reality: a clock, a calendar, and a map of Missoula. Calendars and clocks were not instruments of vital importance in the refugee camp where they had spent their lives. They signified that time was moving, while in the refugee camp, it seemed to stand still.

A neighborhood child named Brittany had clambered up to the apartment from her home downstairs. She was sidling up to the keyboard that Joel kept in one corner to compose church music. “Brittany, don’t touch,” Joel said gently. “Don’t make trouble.” He smiled as the English phrases came easily out of his mouth.

“Tell me more about the camp,” I said.

“Our houses were very small,” he said. “Like this room only. For seven people. So it was very bad. Very bad conditions. They give for one person a cup of cornmeal for a day.” He showed me the size of the cup. “We lived in very bad conditions all my life. All the time, every day. They measure the corn meal out in one month. Also beans.” He showed me with his fingers spread about an inch. “And some oil.”

But harder than the conditions was the sense of stasis, of having no way to begin a life. “I ask, ‘How can I start to live? What can I do? How can I give my effort to my children so they may eat and have a house?’”

|

|

Bartolomé Esteban Murillo, The Flight into Egypt (1647–1650).

|

Once entering the pool of refugees to be resettled, the family had no choices about their direction. Less than one percent of all the world’s displaced people are resettled in a third country. In Joel and Bikeyombe’s case, the UN decided who was in line for Canada and who for the United States, who would go to Europe and who would simply sit in Tanzania and wait. When the family arrived in Montana, they had never heard of it. They got off the plane and asked, “Where are we?”

When we turn to the Gospel this week, we are plunged into the worldwide reality of displacement. The story tells us that while Jesus was still an infant, Mary and Joseph fled to Egypt to escape persecution by King Herod. While the historicity of this particular incident is open for debate, the underlying human condition is not. There are modern-day Herods everywhere. There are despots and dictators the world over who care more about their own power than about human life. These flights for safety are undertaken daily. One of the things that startles us about Alan Kurdi is that he is just one child of millions.

Jesus’s own human story is rooted in the trauma of displacement and in the experience of suffering. Jesus didn’t get very many cozy minutes in the manger before he was, homeless at birth, uprooted again, crossing dangerous borders and dangerous regions to find refuge in Egypt. Even after finding some safety in Egypt, Jesus’s family returned to Judea only to flee again to Galilee, where they settled at last in Nazareth. “Since therefore the children share flesh and blood, he himself likewise shared the same things,” the writer of Hebrews says (2:14).

We use words like “displacement” and “trauma” perhaps to abstract ourselves from the details of what it means to be a refugee. Both the Gospel and the photograph of Alan Kurdi don’t allow us this privilege. The reality of being a refugee is found in the details: being deprived of choice, having food meted out in tiny cupfuls, making dangerous crossings in the hope that you will find something livable on the other side.

|

|

Luc-Olivier Merson, Rest on the Flight into Egypt (1879).

|

I met Mustafa and Wahiba and their three small children in a refugee house in Calais, where they were staying and attempting to cross into the United Kingdom. Over several years they had traveled from Sudan, through Italy, to this far northern stretch of France. On their previous attempt to board the smugglers’ boats, Wahiba had tripped in one of the holes intentionally dug by French police to prevent refugees from climbing into the boats. She had broken her ankle. The family of five was taking time to rest and heal before trying again. All their hopes were pinned on the UK, despite terrible stories of the treatment of refugees there. “We will be born again there,” Mustafa said confidently. “The day we arrive there will be our birthdays and our anniversaries and everything all together.”

In Hebrews 2:18 we read, “Because he himself was tested by what he suffered, he is able to help those who are being tested.” What kind of help? I wondered, as Mustafa and Wahiba’s small son and I built a rocket ship out of Legos. Will he keep the boat afloat in the water? Will he help them be met with kindness and understanding? Will empathy prevail, since it is the one thing necessary? Is there a Mary Poole waiting in Dover?

After I met Wahiba and Mustafa and their children, I kept scanning the website that records crossings in the English Channel. For days there was nothing at all. No boats. No arrivals. And then finally, one day, I saw that 155 people had crossed overnight. But I will probably never know if Mustafa and Wahiba were among them. Nor will I know what happened next, if they found the welcome they needed, if they were answered in their distress.

Weekly Prayer

Thomas Merton (1915–1968)

Through every precinct of the wintry city

Squadroned iron resounds upon the streets;

Herod’s police

Make shudder the dark steps of the tenements

At the business about to be done.Neither look back upon Thy starry country,

Nor hear what rumors crowd across the dark

Where blood runs down these holy walls,

Nor frame a childish blessing with Thy hand

Towards that fiery spiral of exulting souls!Go, Child of God, upon the singing desert,

Where, with eyes of flame,

The roaming lion keeps thy road from harm.

Thomas Merton (1915–1968) was an American Catholic monk, poet, and writer on spiritual and contemplative themes. He entered the Trappist Abbey of Gethsemani near Louisville, Kentucky, but spent his later life traveling widely and exploring Buddhist as well as Christian practice. This poem is from Thirty Poems (New Directions, 1944).

Amy Frykholm: amy@journeywithjesus.net

Image credits: (1) WikiArt; (2) WikiArt; and (3) Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.