From Our Archives

For earlier essays on this week's RCL texts, see Dan Clendenin, “Why Do You Come To Me?” (2023); Debie Thomas, Stepping In (2020) and Thin Place, Deep Water (2017); Dan Clendenin, A Shocking Request and a Stupendous Claim (2014), An Acute Embarrassment (2011), and Wading into the Waters (2008).

This Week's Essay

By Amy Frykholm, who writes the lectionary essay every week for JWJ.

Acts 10:39: “We are witnesses to all that he did.”

For Sunday January 11, 2026

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year A)

Psalm 29

Acts 10:34–43

Matthew 3:13–17

In comparative theologian John Thatamanil’s classes at Union Theological Seminary in New York City, he asks his students to “imagine no religion,” just as John Lennon did in his famous song from 1971. “I don’t actually think the song is that great theologically,” he told me, “but I’m very serious about the ‘imagine no religion’ part.”

We’ve long had our traditions, he explains, but our traditions have not long been religions. Religion is a very specific concept that developed during the Enlightenment, when classification became a cultural obsession in Europe. When the idea that there could be such a concept as “secular” emerged, it followed there would be a corollary concept of “religious.” We can’t have one without the other.

But if we follow Thatamanil’s experiment of imagining no religion, what do we find? Imagine, for example, that John’s baptizing in this week's gospel was not about incorporating anyone into a particular religion, but instead about an initiation for an inner journey. Imagine that when Jesus said, “Follow me,” he didn’t mean “become a Christian,” but instead meant something like, “Become so committed to truth and love that you are willing to give everything up for it.” Imagine that when in Acts 10 Peter says “Lord of all,” he in fact means “all.”

Only in recent centuries do we encounter the idea that some of us are religious and others are not. Protestantism has a unique role to play here. In the 18th century Protestants devoted much time and effort to declaring what was and wasn’t a “religion," and many of those ideas have carried over into our own understandings and what happens when we try to enter into dialogue with other traditions. Protestantism has scripture; therefore all religions must have scripture. Protestantism enshrined belief as central to religion; therefore all religions must have belief. And so on.

|

|

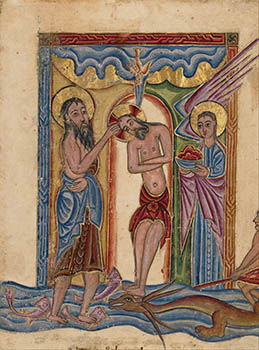

Mesrop of Khizan, The Baptism of Christ (17th c.).

|

In this week’s lectionary reading from Acts, Peter’s speech comes after he has experienced a transformative dream. I imagine him feeling unsettled. Before the dream, Peter has a clear idea of what it means to be a Jewish man. He understands and follows Jewish law. But in the dream, God turns things upside down. God shows Peter all kinds of animals, clean and unclean according to Jewish law. Peter reiterates his understanding, “I have never eaten anything impure or unclean” (Acts 10:14).

God’s answer is startling and challenging. “Consider nothing unclean that I have made” (Acts 10:15). From this vision, Peter understands a challenge to the dietary rules that have shaped his life, but even more radically, he also understands that God is saying something about people, about human beings who come from other places and follow other ways of life, like ritually impure, “dirty” Gentiles. “God has shown me that I should not call any person unclean," (Acts 10:28).

Cornelius is one such person. He is a Roman centurion, and it isn’t immediately clear what investment he has in these proceedings. But like Peter, he has been challenged by a dream to open the doors to his understanding wider. He’s been commanded to bring this Jewish tanner’s guest (a difference in both tradition and class) to his house and listen to whatever he has to say (Acts 10:5). He doesn’t really have a question. He relays his own experience and says in essence, “Tell me whatever you have to tell me” (Acts 10:33).

There is an astonishing humility in Peter’s response. “I truly understand that God shows no partiality,” he begins. I hear a tenderness in Peter’s words that comes when we are in the midst of upending our understanding of things, when foundations have been shaken. For me, as perhaps for Peter, this has happened most profoundly when I have encountered someone who is different from me — who believes different things, has different practices, has a worldview that incorporates things that I didn’t know were possible.

|

Peter responds to Cornelius’s invitation by also telling his story. He tells the gathered people, from another culture and tradition, that not only does God show no partiality, but that God recognizes goodness beyond the boundaries of any particular system of belief and practice. He furthermore says that his own role is one of “witness.” In other words, he doesn’t present himself as someone who has an exclusive possession of the truth, but instead as one who has been asked to observe these proceedings with profound attention. These are not the same things. To possess truth is to believe that it belongs to you and not to others. Peter no longer sees it that way.

Now, he is a witness. He is asked to hold the story and relay his own experience. He begins in Galilee with John’s baptism. “God anointed Jesus of Nazareth with the Holy Spirit and with power,” Peter relays (Acts 10:38). Those who were “chosen by God as witnesses” were able to see with their own eyes the good that was done. Then they observed Jesus’ death and resurrection. They “ate and drank with him after he rose from the dead” (10:41). Now they were being asked to tell this story beyond the borders of Judea and Galilee and their own narrow conception of Judaism.

I wonder if Peter’s approach to this conversation tells us something about what it might mean to “imagine no religion.” Imagine that we each carry in our experience something of the divine to which we are witnesses, and it is our task to convey that. I think of Mary Oliver’s lines: “Pay attention. Be astonished. Tell about it.”

I wonder too, if in our own day and age, this is what it might mean to be the holder of a tradition. We don’t possess it. We didn’t create it. It doesn’t belong to us, but is a part of our experience, and we are witnesses to it. If anything, it possesses us.

There is a way of carrying our tradition forward that is too open. We might say: it doesn’t matter what’s been given to us. Why bother with it? It is irrelevant and the culture and society have moved on. We might as well all become secular. And there is a way of carrying the tradition forward that is too closed — it is this way and no other. I am right and you are wrong.

|

Peter is delicately proposing a third option, an option that is true to his own experience. In this case, his life becomes a witness to the extraordinary things that he has experienced. He has been asked to bring that story into a diverse society and find a way to convey it that makes sense to people who have other frameworks and other worldviews.

Thatamanil notes that one of the first things that a contemporary Christian must do to enter this conversation is to acknowledge, as Peter does, the universality of God’s love. “If I’m truly, as a Christian, to affirm...that God so loved the world, then divine disclosure must be happening far beyond the boundaries of the Christian tradition.” From that understanding flows the ability to speak our own witness and to receive the witness of others.

Theologian Ilia Delio adds, if the Christian message of incarnation is that God has become matter, then this isn’t a witness that one part of God became matter, but that the “whole infinite, eternal God Creator has become matter.” Christ is, she writes, “the communion of divine personal love expressed in every created form of reality — every star, leaf, bird, fish, tree, rabbit, and human person.”

This story of divine love is the one that Peter is compelled to share with Cornelius. It is not a story about a particular religion, but a story about the whole of creation.

Weekly Prayer

Brian Wren (b.1936)

Good is the flesh that the Word has become,

good is the birthing, the milk in the breast,

good is the feeding, caressing and rest,

good is the body for knowing the world,

Good is the flesh that the Word has become.Good is the body for knowing the world,

sensing the sunlight, the tug of the ground,

feeling, perceiving, within and around,

good is the body, from cradle to grave,

Good is the flesh that the Word has become.Good is the body, from cradle to grave,

growing and aging, arousing, impaired,

happy in clothing, or lovingly bared,

good is the pleasure of God in our flesh,

Good is the flesh that the Word has become.Good is the pleasure of God in our flesh,

longing in all, as in Jesus, to dwell,

glad of embracing, and tasting, and smell,

good is the body, for good and for God,

Good is the flesh that the Word has become.Brian Wren (b.1936) is an internationally published hymn-poet and writer, whose works appear in hymnals across all Christian traditions. He received a D.Phil. degree in Old Testament Theology from Oxford University. This is an excerpt from Good Is the Flesh: Body, Soul, and Christian Faith, edited by Jean Denton (Morehouse Publishing, 2005).

Amy Frykholm: amy@journeywithjesus.net

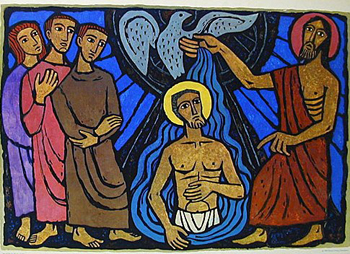

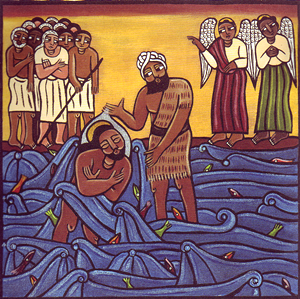

Image credits: (1) Wikipedia.org; (2) Third Way Living by Ken Corder; and (3) Gymnos Aquatic Saints.