For Sunday May 22, 2022

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year C)

Acts 16:9–15

Psalm 67

Revelation 21:10, 22 –22:5

John 14:23–29 or 5:1–9

From Our Archives

For earlier essays on this week's RCL texts, see my essays Bottled Lightning (2007); Celtic Blessings for All The World (2013); Taking the Long View (2016); and the essay by Debie Thomas, The Question That Hurts (2019).

When I launched Journey with Jesus on June 23, 2004, I called it a "weekly webzine for the global church." That was purely aspirational at the time — I had no clue whether we would even survive, much less reach a "global" audience. But now, eighteen years and eleven million page views later, global is exactly what we are. Every month JWJ serves readers in 130 countries. About 33% of our traffic comes from outside the United States.

The readings this week remind us that to be Christian is to be global. There's no other way.

The lectionary poses a radical question: is the core of my personal identity formed more by nationalistic and cultural values or by the kingdom of God that was embodied in Jesus? Christian globalism calls us to care for every country and people as much as we care for our own land.

Psalm 67 was written 2500 years ago by an unknown poet from an insignificant tribe, and yet it describes a God who is anything but territorial or parochial. The psalmist's God is global. In seven verses he mentions some variant of "all the peoples" ten times.

He imagines God's salvation to "all nations." His God "rules the peoples justly and guides the nations of the earth." He thanks God for the harvest, and asks that "all the ends of the earth" be similarly blessed. Coming from an ancient writer of a geo-politically obscure people, I'm always amazed at the global purview of the Hebrew psalms.

|

|

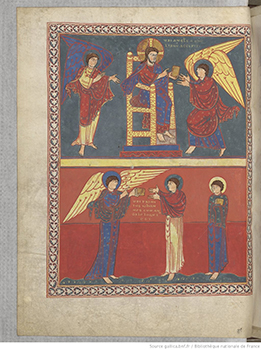

John receives his revelation, Saint-Sever Beatus, Romanesque illuminated manuscript, 11th century,

|

Psalm 67 pushes us beyond our narrow political and ethnocentric boundaries to embrace every "other." John's vision in Revelation 21–22 does the same thing.

At first glance the "new heaven and new earth" look narrowly Jewish — a surreal Jerusalem with twelve gates with twelve guardian angels representing the twelve tribes of Israel.

In fact, John's heavenly Jerusalem is a cosmopolitan city par excellence. Its citizens come from "every nation, tribe, people, and language." All the nations of the world "will walk by its light, and the kings of the earth will bring their splendor into it." Every corner of the globe brings their unique gifts — "the glory and honor of the nations will be brought into it."

There's a "tree of life" in the City of Jerusalem, reminiscent of the "tree of life and the tree of knowledge of good and evil" in the Garden of Eden. But this heavenly tree is for "the healing of the nations" rather than for the fall of humanity.

When God elected Israel four thousand years ago, says Elie Wiesel, they were a "singular" people, but they were not a "superior" people. The election of Israel did not mean the exclusion of Gentiles. In choosing one people, God blessed every nation. He promised Abraham that in him "all the families of the earth will be blessed" (Genesis 12:3).

God repeated this Abrahamic covenant to Isaac, and reiterated his intentions for all the world: "in you, Isaac, all nations on earth will be blessed" (Genesis 26:5). And when Isaac's son used a rock for a pillow and dreamed a dream at Bethel, God repeated verbatim: "In you, Jacob, all peoples on earth will be blessed." (28:14).

This ancient promise has become an empirical reality in Jesus, "the son of Abraham" (Matthew 1:1). Luke's book of Acts for this week begins in the holy city of Jerusalem, expands geographically with Paul's three "missionary journeys," and ends in the imperial city of Rome. Under house arrest there, Paul's last recorded prayer before his martyrdom was for "all nations" (Romans 16:26).

The historian Garry Wills once described Paul as a "heroic traveler" who logged more than 10,000 miles spreading the good news of God's love for all the world. For Paul, God wasn't the God of Jews alone. In Ephesians, he makes a clever play on words to say that God is the father of "every family in heaven and on earth," the patera of every patria — the "father from whom every family derives its name."

|

|

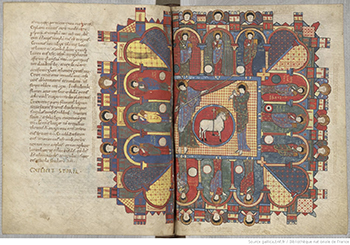

The world map from the Saint-Sever Beatus manuscript, 11th century. The map measures 37 x 57 centimeters.

|

But even the intrepid Paul barely made a beginning. Starting with a few uneducated, bedraggled disciples, today about a third of the world identifies itself as Christian, nearly twice as many as those who follow Islam or Hinduism. Today, John's depiction of a globalized heaven beyond history has been fulfilled on earth in history.

For many centuries, much of Christianity was white, western, and male. The main actors were in Geneva, Rome, Paris, London, and New York. But as the Kenyan theologian John Mbiti has observed, that day is long gone.

Today the vibrant centers of Christianity are in places like Kinshasa, Buenos Aires, Addis Ababa, and Manila. Two-thirds of Roman Catholics now live in the global south. If the demographers are right, in fifty years half of the world’s Christian population will be in Africa and Latin America, and only about 20% of believers will be non-Latino whites. A Nigerian pope? Don't bet against it.

Global minded Christians are geographic, cultural, national and ethnic egalitarians. For us there's no geographic center of the world, but only a constellation of points equidistant from the heart of God. Proclaiming that God lavishly loves all the world, each person, and every place, the gospel does not privilege any country as exceptional.

A lot has been written about American exceptionalism and empire. It's an important and complicated subject. In terms of economic, political, military, scientific and cultural influence, America is unrivaled. In that sense, it's fair to say that America is "exceptional," although it's debatable how long this will last, or whether such hegemony is good or bad.

|

|

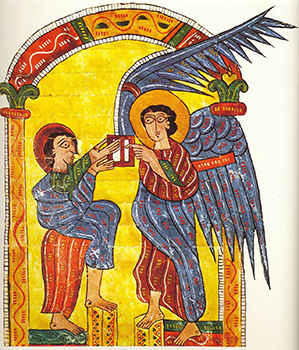

The angel gives John the letter to the churches of Asia, Beatus Escorial, Spanish illuminated manuscript, c. 950.

|

But from a Christian point of view, America is no more or less "exceptional" in God's eyes than any other country. While allowing for a natural love and pride for your own country ("there's no place like home"), in the long run, Christian globalism subverts every form of nationalism.

Patriotism is one thing; it's to be expected. But nationalism, as CS Lewis observed, believes that my nation is "markedly superior to all others." Lewis once encountered someone who espoused such noxious nationalism. He asked him, "doesn't every nation think of itself as the best?"

The person responded in all seriousness, "Yes, but in England it is true."

Lewis concludes, "To be sure, this conviction had not made my friend (God rest his soul) a villain; only an extremely lovable old ass. It can however produce asses that kick and bite. On the lunatic fringe it may shade off into that popular Racialism which Christianity and science equally forbid."

About a generation after John wrote the book of Revelation, the Letter to Diognetus captured this ambivalent relationship between our diverse geo-political identities and our common Christian confession. The author compares believers to resident aliens.

For the Christians are distinguished from other people neither by country, nor language, nor the customs which they observe. For they neither inhabit cities of their own, nor employ a peculiar form of speech, nor lead a life which is marked out by any singularity. The course of conduct which they follow has not been devised by any speculation or deliberation of inquisitive men; nor do they, like some, proclaim themselves the advocates of any merely human doctrines. But, inhabiting Greek as well as barbarian cities, according as the lot of each of them has determined, and following the customs of the natives in respect to clothing, food, and the rest of their ordinary conduct, they display to us their wonderful and confessedly striking method of life. They dwell in their own countries, but simply as sojourners. As citizens, they share in all things with others, and yet endure all things as if foreigners. Every foreign land is to them as their native country, and every land of their birth as a land of strangers.

|

|

The New Jerusalem, Saint-Sever Beatus, Romanesque illuminated manuscript, 11th century.

|

This collision of Christianity with politics, geography, ethnicity, and culture reveals a historical paradox, as the Yale historian Jaroslav Pelikan observed. There has never been a time, place, culture, language, philosophy, science, or world view with which the gospel has been entirely compatible, but it's equally true that "there has also never been any picture of the world within which the confession of the faith has proved to be altogether impossible."

We all reflect our unique times and places. But we also experience a divided loyalty similar to resident aliens who long for their homelands while living in a foreign country—ultimate loyalty to the city of God and its "politics" of self-sacrificing love, and penultimate loyalty to the city of man and to what Diognetus called its "merely human doctrines." Our deepest identity, Paul says, is a spiritual "citizenship in heaven" (Philippians 3:20).

Weekly Prayer

When I was in graduate school I came across this prayer by Søren Kierkegaard, which I liked so much that my wife printed it in calligraphy. For many years it hung in my office.

Herr! gieb Uns blöde Augen

für Dinge, die nichts taugen

und Augen voller Klarheit

in alle Deine Wahreit.

Lord! Give us weak eyes

for things that do not matter

and eyes full of clarity

in all your truth.

NOTE: On John Mbiti, see Philip Jenkins, The Next Christendom: The Coming of Global Christianity (Oxford, 2002); and his sequel, The New Faces of Christianity; Believing the Bible in the Global South (Oxford, 2006).

Dan Clendenin: dan@journeywithjesus.net

Image credits: (1) Wikipedia.org; (2) Wikipedia.org; (3) Wikipedia.org; and (4) Wikipedia.org.Wi