From Our Archives

For earlier essays on this week's RCL texts, see Debie Thomas, Has It All Been For Nothing? (2022), Are You the One? (2016); Dan Clendenin, Lo, Faithful Virgin (2013); Sara Miles, My Soul Proclaims (2007); and Dan Clendenin, Where God Was Homeless (2004).

This Week's Essay

By Amy Frykholm, who writes the lectionary essay every week for JWJ.

Matthew 11:9: “What, then, did you go out to see?”

For Sunday December 14, 2025

Third Sunday in Advent

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year A)

Psalm 146:5–10 or Luke 1:46b–55

James 5:7–10

Matthew 11:2–11

In Shusako Endo’s novel Deep River, a seemingly hapless character Ōtsu goes to Paris to study for the priesthood. He writes long letters to his former lover, Mitsuko, expressing all of the ways that his training is not going well.

There is a difference, he says, between his superiors and himself that is so deeply engrained, they do not seem to be able to overcome it. He states that the trouble has mostly come from his sense that the world is infused with God’s presence, that God’s presence is everywhere and in everything. His superiors derisively call this worldview “pantheistic.”

But he says that he “can’t bear those who ignore the great life force that exists in Nature.” His superiors, he says, will never be able to understand just how important, how essential these lines are from the haiku poet Bashō:

when I look closely

beneath the hedge, mother’s heart

flowers have blossomed.

What is it that makes those lines from Bashō so significant in the novel? Why does Endo highlight them? On the surface, they couldn’t be simpler. And what blocks Ōtsu’s superiors from the perception that he thinks they lack?

The “mother’s heart flower” is a common plant in Japan, the nazuna. This is not the rare lotus. It is a grass flower, and it grows by itself without any tending. Bashō’s attention is drawn to the beauty of the utterly ordinary. And it isn’t that nazuna is suddenly beautiful; it’s that the poet’s way of seeing it has changed. Nazuna is there all the time, doing its thing, blooming beneath hedges.

|

|

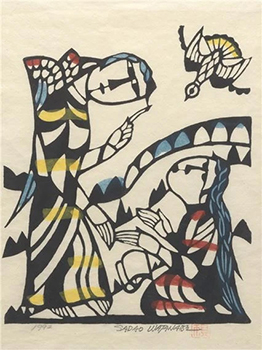

Sadao Watanabe, The Annunciation (1992).

|

“I don’t think,” Ōtsu tells his superiors, “God is someone to be looked up to as a being separate from man, the way you regard him. I think he is within man, and that he is a great life force that envelops man, envelops the trees, envelops the flowers and the grasses.”

Endo is referring, perhaps, to an essay written by D.T. Suzuki, a religious scholar and philosopher. In his essay titled “East and West,” Suzuki compares this same haiku to a famous poem by Tennyson, “Flower in the Crannied Wall.” Both poems express joy at discovery, but Suzuki notes that the haiku poet marvels at the deep feeling that the blossoms stir in him, at the interconnection between his own movements in the world and the flower’s. Tennyson reaches out, plucks the flower, and analyzes the now-dead bloom intellectually, imagining that through his analysis he might “know what God and man is.”

These themes of recognition, seeing, analysis, and discovery are found throughout this week’s Gospel text. How do they place us between Bashō and Tennyson? What kind of seeing is being asked of us?

The passage from Matthew contains three different Greek verbs for “seeing.” The first is the most common and basic — blepo — “tell John what you hear and see” (Matthew 11:4). Give John a direct report from your own experience, what your own ears have heard and what your own eyes have seen. This is the same verb used to describe the blind receiving sight.

|

|

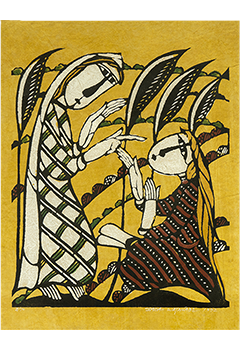

Sadao Watanabe, Nativity (not dated).

|

But the next verb is different and seems to be carefully chosen here. “What did you go out into the desert to look at?” Jesus asks the crowd (Matthew 11:7). Here the verb is theaomai — and the sense is “to make a spectacle out of.” It’s the same verb that gives us our word “theater” in English. There’s a little bit of an edge here. What did you come to make a spectacle out of? Jesus challenges his listeners to turn inward and look at their motivations.

The answer that he proposes to them after this first rhetorical question is “a reed shaken by the wind” (Matthew 11:7). It is a tender image: a reed is at once strong and vulnerable. Here it is tossed by an unseen force. As an image for John, who is now in prison, it might cause a sting. They went out into the desert to make a spectacle of someone, perhaps out of superficial curiosity, and what they found was a forceful person, but one who will soon die in prison.

But then Jesus asks the question again, this time with a different verb for “to see,” one that the Gospels place in his mouth most commonly, orao. This is a verb that can mean both to see and to understand, that in fact links the act of seeing with the act of understanding.

When he asks the question a second time, “What did you go out to see?” (Matthew 11:8), his second rhetorical answer is a little ridiculous, perhaps meant to spread laughter across the crowd as they remember the roughness of John the Baptist. “A man in soft robes?” That kind isn’t found here. If you want to find that kind, go to the palaces.

Finally in verse 9, Jesus repeats the exact question as before with the same verb orao, but this time perhaps nuanced in the direction of understanding or perceiving instead of mere seeing: “What did you go out to understand?” This time his answer seems to walk them closer toward a different kind of seeing, a spiritual sight. A prophet? Yes, and more than that, one who prepares the way.

|

|

Sadao Watanabe, Healing the Lame (1972).

|

Does “understand” in this case mean “analyze,” as Tennyson analyzes the now plucked flower? Does it mean that in John the Baptist, the plucked flower, we are now supposed to “know what God and man is”? Or does it mean something more along the lines of Bashō and Endo: now we see how God is revealed in the lowly and the ordinary; now we see our own sight transformed and our own hearts opened?

A haiku, like John the Baptist, points the way. By noticing the poet noticing the nazuna, we too begin to see differently, transformationally.

This kind of seeing might be the beginning of the way of justice that this week’s lectionary passages call us toward. As our eyes and hearts are opened, we begin to see how the hungry are fed (Psalm 146:7; Matthew 1:53), how the lame walk (Isaiah 35:6; Matthew 11:5), how knees and hearts are strengthened (Isaiah 35:3–4). As we attend to what we think of as “lowly” (Matthew 1:48), accompanying it with our capacity for joy and perception, the Song of Mary takes root and thrives inside us.

“My soul magnifies the Lord,

And my spirit rejoices in God my Savior.”

Weekly Prayer

Howard Thurman (1899–1981)

Open unto me—light for

my darkness.Open unto me—courage for

my fear.Open unto me—hope for

my despair.Open unto me—peace for

my turmoil.Open unto me—joy for

my sorrow.Open unto me—strength for

my weakness.Open unto me—wisdom for

my confusion.Open unto me—forgiveness for

my sins.Open unto me—tenderness for

my toughness.Open unto me—love for

my hates.Open unto me—Thy self for

my self.Lord, Lord, open unto me!

Howard Thurman (1899–1981) was an American philosopher, theologian, mystic, and Civil Rights leader who was a key mentor to Martin Luther King Jr. and whose work grows in significance in contemporary contemplative movements. Among his many books are Jesus and the Disinherited (1951) and The Inward Journey: Meditations on the Spiritual Quest (1961). This poem is from Meditations of the Heart (Harper, 1953), p.188–189.

Amy Frykholm: amy@journeywithjesus.net

Image credits: (1) MutualArt; (2, 3) Mount Angel Abbey.