For Sunday February 20, 2022

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year C)

Genesis 45:3-11,15

Psalm 37:1-11, 39-40

1 Corinthians 15:35-38, 42-50

Back in December, the New York Times ran an essay with a ruefully funny title: “Rudeness Is on the Rise. You Got a Problem With That?” In it, Jennifer Finney Boylan laments the rising tide of rage and meanness in our Covid-weary culture. “How,” she asks, “do we respond to a world under stress, a culture in which the guardrails of so-called civility are gone? The evidence of that stress is everywhere. In airports, and then in the skies, you can find airline passengers angry about wearing masks, angry about inspection of firearms in their carry-ons, seemingly angry about, well, everything. Close to home, things aren’t much better, and it comes from both sides of our ideologically divided society.”

Whether our tempers flare on an airplane, a highway during rush hour, a long queue at a restaurant, or a hospital waiting room, we seem to have lost our capacity for gracious communal living. We bristle at new Covid restrictions. We assume that folks we don’t even know are "out to get us." We “cancel” our nemeses — both real and imagined.

So of course, our lectionary readings this week will cause us some necessary discomfort. Honestly, when I looked them up a few days ago, I flinched. Why? Because the readings are about forgiveness. They are about the work of forgiveness, and the challenges they pose to our “shove or be shoved” culture are daunting.

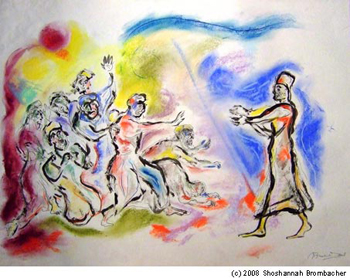

In our Old Testament reading, Joseph forgives his older brothers for sending him into a lifetime of hardship: “Do not be distressed, or angry with yourselves because you sold me here; for God sent me before you to preserve life.”

The Psalmist exhorts his readers to “refrain from anger, and forsake wrath,” because “fretting” over evil only leads to more evil.

|

In his first epistle to the Corinthians, Paul writes about “seeds” that must die before new life can emerge. Dare I suggest that these “seeds” might include our resentments, our grudges, our wounds, our prejudices? Paul reminds us that we cannot know ahead of time what God will do with the “bare” and perishable seeds we sow into the ground. All we can do is consent to “die” to everything that hinders new life, and trust that God will raise our dishonor and weakness into glory and power.

And finally, in the Gospel of Luke, Jesus continues his “Sermon on the Plain” with teachings so countercultural, we hardly know what to do with them even now, two thousand years after he spoke them: “Love your enemies, do good to those who hate you, bless those who curse you, pray for those who abuse you. If anyone strikes you on the cheek, offer the other also; and from anyone who takes away your coat do not withhold even your shirt.” And again: “Be merciful, just as your Father is merciful. Do not judge, and you will not be judged; do not condemn, and you will not be condemned. Forgive, and you will be forgiven.”

These readings don’t leave us much wiggle room, do they? No matter what we think of it, our call as Christians is to walk in love. To practice mercy. To refuse revenge, recrimination, and rage. To give our offenders second, third, fourth, and even hundredth chances.

But how do we live into this mind-boggling call? How do we even begin? Perhaps we can begin by affirming what forgiveness is not.

First, forgiveness is not denial. Forgiveness isn’t pretending that an offense doesn't matter, or that a wound doesn't hurt. Forgiveness isn't acting as if things don't have to change. Forgiveness isn’t allowing ourselves to be abused and mistreated, or assuming that God has no interest in justice. Forgiveness isn't synonymous with healing or reconciliation. Healing has its own timetable, and sometimes reconciliation isn't possible. In fact, sometimes our lives depend on us severing ties with our offenders, even if we've forgiven them. In other words, forgiveness is not cheap.

Secondly, forgiveness isn’t a detour or a shortcut. Yes, Christianity insists on forgiveness. But it calls us first to mourn, to lament, to burn with zeal, and to hunger and thirst for justice. Forgiveness in the Christian tradition isn't a palliative; it works hand-in-hand with the arduous work of repentance and transformation. In other words, there is nothing godly about responding to systemic evil with passive acceptance or unexamined complicity.

Thirdly, forgiveness is not instantaneous. Not if we’re honest. Forgiveness is a process — a messy, non-linear, and often barbed process that might leave us feeling healed and liberated one minute, and bleeding out of every pore the next. In my experience, no one who says the words, "I forgive you" gets a pass from this messy process, and no one who struggles extra hard to forgive for reasons of temperament, circumstance, or trauma should feel that they're less godly or spiritual than those who don't. Consider that before Joseph forgives his brothers, he wrestles with a strong desire to scare and shame them. In fact, he does scare and shame them. Forgiveness is something Joseph has to arrive at, slowly and painfully. There is no cathartic, "altar call" moment when the hurts of his past slip off his back and roll away. There is only life, lived one layered, complicated, and unsentimental moment at a time.

|

Why? Because he — like all of us — is created for goodness. For a just and nurturing world. For a family that will keep him safe. And just like Joseph, when we experience that good world being ripped away from us, it is appropriate — it is human and healthy — to react with horror. One of the great gifts of Christianity is that it takes sin and sin’s consequences seriously. Sin wounds. Sin breaks. Sin echoes down the ages. And so forgiveness isn't an escalator; it's a spiral staircase. We circle, circle, and circle again, trying to create distance between the pain we’ve suffered and the new life we seek. Sometimes we can’t tell if we’ve ascended at all; we keep seeing the same, broken landscape below us. But ever so slowly, our perspective changes. Ever so slowly, the ground of our pain falls away. Ever so slowly, we rise.

Okay. If forgiveness isn’t denial or a detour, if forgiveness isn’t quick — then what is it? What is Jesus asking of us when he invites us to love, bless, pray, give, lend, do good, withhold judgment, extend mercy, and turn the other cheek?

In her popular memoir, Traveling Mercies, Anne Lamott writes that withholding forgiveness is like drinking rat poison and then waiting for the rat to die. If Lamott is correct, then I think forgiveness is choosing to foreground love instead of resentment. If I'm consumed with my own pain, if I've made injury my identity, if I insist on weaponizing my well-deserved anger in every interaction I have with people who hurt me, then I'm drinking poison, and the poison will kill me long before it does anything to my abusers. To choose forgiveness is to release myself from the tyranny of bitterness. To give up my frenzied longing to be understood and vindicated by anyone other than God. To refuse the seductive lie that revenge will make me feel better. To cast my hunger for justice deep into God’s heart, because justice belongs to God, and only God can secure it.

I wonder if we're often squeamish about forgiveness because we misunderstand the nature of unconditional love. Foregrounding God's all-embracing love doesn't for one second require us to relativize evil. If it did, God's love would be cruel and weak, not compassionate and strong. But where we humans make love and judgment mutually exclusive — where we cry out for revenge, retribution, and punishment — God holds out for restorative justice. A kind of justice we can barely imagine. A kind of justice that has the power to heal both the oppressed and the oppressor.

|

Secondly, I think forgiveness is a transformed way of seeing. When Joseph forgives his brothers, he reframes the horrible events of his life to include the redemptive artistry of God: “God sent me before you to preserve life.” To be clear: this doesn’t mean that God willed Joseph’s brothers to abuse and abandon him. I don’t believe that abuse is ever God’s will. Rather, what Joseph is saying is that God is always and everywhere in the business of taking the worst things that happen to us, and going to work on them for the purposes of multiplying wholeness and blessing. Because God is in the story, we can hope for the resurrection of all things. There will be another turn, another chapter, another path, another grace. As Jesus promises his listeners, the measure we give will be given back to us: "A good measure, pressed down, shaken together, and running over.” Because God loves us, we don’t have to forgive out of scarcity. We can forgive out of God’s amazing abundance.

At the end of her New York Times essay, Boylan (a trans woman) recounts going out to dinner one night with her mom, and receiving cruel treatment from their transphobic waiter. Boylan walks out feeling hurt and sad, but she notices with surprise that her mom is unfazed. When she asks why, her mom says, “Oh Jenny, you know he didn’t really mean it.”

Boylan almost retorts, “Of course he meant it!” But then she realizes what her mom is saying: “She wasn’t really talking about the man before her; she was talking about a better version of him, a self he had not been able to become, but in whom she had not lost faith. He was not yet that man. But, she felt, in receiving the gift of kindness, and of grace, maybe he still had a shot."

The work of forgiveness is some of the hardest work we can do in this world. It is also some of the most important work we can do in this world. So. May we stop drinking the poison of incivility and bitterness. May we glimpse the “better selves” that reside within the people who do us harm. May we rise. And may we taste the full measure of the freedom that awaits us when we choose to forgive.

Debie Thomas: debie.thomas1@gmail.com

Image credits: (1) 567ministries.com; (2) Chabad.org; and (3) Pilgrim-info.com.