From Our Archive

Sam Rowen, Remembering the Protestant Reformation (2007); Helen Brooks, Reformation Sunday (2010); Dan Clendenin, Two Cheers for the Reformation (2017); Debie Thomas, Learning to See (2016).

For Sunday October 30, 2022

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year C)

Habakkuk 1:1–4; 2:1–4 or Isaiah 1:10–18

Psalm 119:137–144 or Psalm 32:1–7

2 Thessalonians 1:1–4, 11–12

Luke 19:1–10

This Week's Essay

The day after All Hallow's ( 'holy') Eve on October 31 — better known as Halloween, I especially enjoy All Saints Day on November 1. The gospel this week about Zacchaeus is the perfect story to consider the saints who have impacted our lives. And as he so often does, Jesus challenges our pious assumptions about both saints and sinners.

The story of Zacchaeus occurs only in Luke. It comes near the end of Luke's "travel narrative" that begins in Luke 9:51 in Galilee: "When the days drew near for Jesus to be taken up, he set his face to go to Jerusalem." Luke repeats himself at least eight times in this travel narrative, saying that Jesus is heading inexorably to Jerusalem. The journey ends with the "triumphal entry" of Jesus into Jerusalem, right after his encounter with Zaccheus seventeen miles away in Jericho.

The name Zacchaeus means righteous, which is pure irony in this story. Luke describes him as the sort of person that we love to hate. He says that Zacchaeus was a "chief tax collector." That is, he was a Jew who collected taxes for the Roman oppressors. So, he was a traitor to the political cause. In the rabbinical literature, tax collectors are akin to robbers.

Luke also says that Zacchaeus was wealthy. And, big surprise, how did a Roman tax collector get wealthy? By extortion and embezzlement. By taking advantage of the elderly, by exploiting the working poor, and by taking care of his cronies. There's an unspoken assumption of corruption here. Zacchaeus is a man who deserves our disdain.

|

|

Mural in Keldby Kirchem Vordingborg Kommune, Denmark, c. 1275.

|

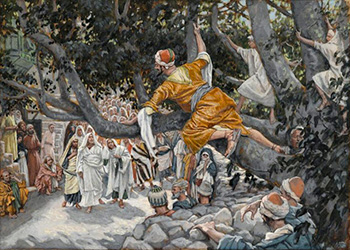

Zacchaeus was not only corrupt and rich, he was famously short. When Jesus passed through Jericho, he was eager to get a look, so he did something utterly undignified for a man of his station. He ran ahead of the crowd, climbed up into a tree, then waited for Jesus to pass by. Imagine a powerful lobbyist in Washington doing something similar during a presidential parade.

When Jesus reached that spot, he looked up, saw Zacchaeus, and told him to come down. He then invited himself to stay with Zacchaeus: "I must stay at your house today." And so Zacchaeus climbed down and "welcomed Jesus gladly."

The response of the crowd was predictable. Luke says that "they began to mutter. 'He has gone to be the guest of a sinner.'" Recall how Jesus called another tax collector, Matthew, to be one of his twelve disciples, and how the religiously scrupulous Pharisees complained that he was a "friend of tax collectors and sinners." In fact, there are twenty-two references to tax collectors in the three synoptic gospels (nine times in Matthew, three in Mark, and ten in Luke).

Luke has returned here to one of his major themes, that Jesus "welcomes sinners" (15:2), he doesn't reject them. No wonder that "many tax collectors" came to him for baptism, and that he often ate at the homes of tax collectors. This theme was the occasion for his three earlier stories about searching for a lost sheep, a lost coin, and a lost prodigal son. And so the story of Zacchaeus ends with this conclusion: "the son of man has come to seek and to save that which is lost." Tax collectors epitomized his mission for the lost-n-found.

Zacchaeus defends himself before the hostile crowd. He says that he'll give half of his possessions to the poor, and that he'll repay fourfold all the people that he's cheated. That would be a long list of angry tax payers.

|

|

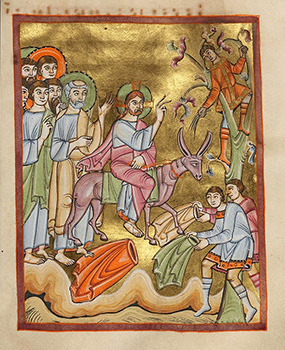

Zaccheus greets Jesus entering Jerusalem, artist unknown, c. 1030.

|

Read in this way, Zacchaeus is a sinner who repents and is converted on the spot. He promises future reparations. He'll make a new start.

But there's another way to read this story in which Zacchaeus isn't a sinner who converts but a saint who surprises. He doesn't make promises about the future, rather, he defends himself and shocks the crowd by appealing to his past.

Both of these interpretations depend on how you translate Luke 19:8, and in particular the verbs that in the Greek text are in the present tense. It's a good example of the complicated interplay between translation and interpretation, and in this instance there's no one correct answer.

Even though the verbs are in the present tense, the typical way of reading of this story follows scholars like Robert Stein and translations like the NRSV and NIV. They render the present tense verbs as a "futuristic present." That is, Zacchaeus the sinner repents and vows that henceforth he'll make restitution.

The second option follows commentators like Joseph Fitzmyer and translations like the KJV and RSV. They render the verbs as a "progressive present tense." In this reading, Zacchaeus is a hidden saint about whom people have made all sorts of false assumptions about his corruption. And so he defends himself: "Lord, I have always given half of my wealth to the poor, and whenever I discover any fraud or discrepancy I always make a fourfold restitution."

The crowd had demonized Zacchaeus as a tax cheat. Jesus praises him as "a son of Abraham."

I like the second reading. It fits with the many times that Jesus calls out good people who are bad and commends bad people who are good.

|

|

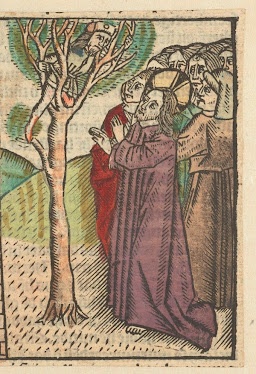

Meester van Antwerpen, Jesus and Zaccheus, c. 1485–1491.

|

Luke has already mentioned several unlikely heroes of faith — a Roman soldier, a "good" Samaritan, a shrewd manager who was commended for his dishonesty, a Samaritan leper who was the only person to give thanks for his healing, and yet another tax collector who was commended as more righteous than a sanctimonious Pharisee (18:10).

So, maybe the story is not about a sinner who shocks us by repenting, but about the crowd that demonizes a person it doesn't like with all sorts of false assumptions.

The Episcopal priest Elizabeth Kaeton notes the several ironies here. The despicable Zacchaeus is the generous one. The traditional interpretation that Zacchaeus is a sinner who's converted "tricks us into committing the very sin that the story condemns. It presents Zacchaeus not as a righteous and generous man who is wrongly scorned by his prejudiced neighbors, but as the story of a penitent sinner."

"Turns out," says Kaeton, that "Zacchaeus does live up to his name. He is, in fact, 'the righteous one.' Turns out, Jesus knew that all along!"

Kaeton thus concludes with a nod to Halloween: "Jesus is once again turning our world upside down, confronting us with our assumptions about who is good and who is evil and demonstrating for us the tricks we play in our minds before we treat one another — one way or another. Like the crowd murmuring about Zacchaeus, it is easy to be blinded by our prejudice of 'those people' and find ourselves accusing the very person or people we should be emulating."

Weekly Prayer

John Berryman (1914–1972)

Master of beauty, craftsman of the snowflake,

inimitable contriver,

endower of Earth so gorgeous & different from the boring Moon,

thank you for such as it is my gift.I have made up a morning prayer to you

containing with precision everything that most matters.

'According to Thy will' the thing begins.

It took me off & on two days. It does not aim at eloquence.You have come to my rescue again & again

in my impassable, sometimes despairing years.

You have allowed my brilliant friends to destroy themselves

and I am still here, severely damaged, but functioning.Unknowable, as I am unknown to my guinea pigs:

How can I 'love' you?

I only as far as gratitude & awe

confidently & absolutely go.I have no idea whether we live again.

It doesn't seem likely

from either the scientific or the philosophical point of view

but certainly all things are possible to you,and I believe as fixedly in the Resurrection-appearances to Peter and

to Paulas I believe I sit in this blue chair.

Only that may have been a special case

to establish their initiatory faith.Whatever your end may be, accept my amazement.

May I stand until death forever at attention

for any your least instruction or enlightenment.

I even feel sure you will assist me again, Master of insight & beauty.

Dan Clendenin: dan@journeywithjesus.net

Image credits: (1) LiturgyTools.net; (2) LiturgyTools.net; and (3) Google Arts & Culture.