From Our Archives

For earlier essays on this week's RCL texts, see Dan Clendenin, Be Careful Where You Sit (2022); Debie Thomas, Places of Honor (2019), Table Manners (2016); Dan Clendenin, Food, the Kingdom of God and a Texas Street Wedding (2013), A Spirituality of Food:"The All-Sufficient Metaphor for Power" (2010), Jesus Does Dinner: Food for Thought for Guests and Hosts (2007), and Code Lunches (2004)

This Week's Essay

By Amy Frykholm, who writes the lectionary essay every week for JWJ.

Hebrews 13:2: “Do not neglect to show hospitality to strangers.”

For Sunday August 31, 2025

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year C)

Psalm 81:1, 10–16

Proverbs 25:6–7

Hebrews 13:1–8, 15–16

Luke 14:1, 7–14

In the spring of 1985 in Sioux Falls, South Dakota, a new ecumenical ministry opened its doors. It was squeezed into a nondescript building next to the downtown Holiday Inn parking ramp. In a direct reference to Luke 14:8, it was called The Banquet.

The group that founded the ministry was a somewhat random collection of representatives from diverse religious communities — clergy and lay people, Catholic and Protestant. They were inspired by what Jo Vaughn Gross, author of a memoir about those early days, called “New Testament hospitality — the teaching of openness to humanity in all its diversity.” Bishop Paul Dudley gave the directive to this group: address food insecurity in the quickly growing city.

To explore the question, the group traveled widely to ministries in other communities. In Milwaukee, they sat with Father Steve Gleiko, a priest at St. Benedict’s Catholic Church. He asked them, “Who is your target ministry?” They looked at one another. Wasn’t it obvious? The poor of course. Wrong, he told them. The target is the whole community: the rich and the poor, the healed and the sick, the blind and the sighted. In this little glimmer of the kingdom of heaven, there would be no division between them.

The core idea of The Banquet was to do, as ambitiously as possible, what Jesus suggested to the Pharisee in Luke 14: create a space where advantaged and disadvantaged people come together; create a common table. The idea was not to have a few hearty and saintly souls “serving the poor,” but to create a context where hundreds of people were welcomed to both serve and to eat, to share with strangers, to crack open cold hearts just a little. As Gross wrote, The Banquet would be a place “where people’s lives might touch, where there was opportunity for connectedness.” This wasn't charity; it was celebration.

|

|

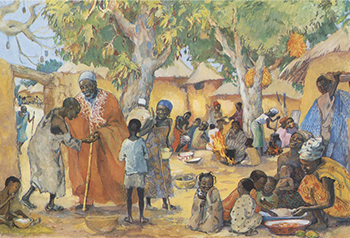

Jean-Baptiste Jean, Community Feast (1996).

|

Key to this was intentional extravagance. Every meal would be overflowing, generous, and abundant. There would be no stingy, soup-kitchen gruel. If they were going to do this, it would be with meat and potatoes, rich soups, steaming casseroles, homemade cookies and sheet cakes, and this being South Dakota in the 1980s, plenty of Jello “salad.” There would be fresh flowers and linens on the tables. When the uninitiated walked into this space, they might say, “Are you preparing for a wedding?” This was intended, Gross writes, to upend reality, “to tell something new.”

The trickiest thing is getting people to consent to this kind of oneness. Those with resources and power might be interested in sharing what they have. But it is quite another thing to sit down at a table and share a meal with a stranger. At The Banquet, this was instituted into practice: everyone who came to serve also sat at the tables and ate. No hiding in the kitchen or behind the coffee pot. The requisite vulnerability and uncertainty was always palpable, even among the boldest and most seasoned volunteers. It is much easier to ask, “Can I help you?” than it is to ask, “Who are you?”

I was 13 years old when I first went to The Banquet. Amidst a dreary November twilight, I was assigned with my father to go out into the alleyway. We poured hot apple cider into Styrofoam cups for people to sip as they waited in line.

I felt awkward, utterly shy. I was grateful to have a question to ask, to have something to hold in my hand. “Would you like some apple cider?” Some of the people smelled like beer mixed with damp and worn winter clothes. Some were children. Some were weary looking parents. Some had little bottles of Tabasco in their coat pockets.

|

|

Jesus Mafa, The Poor Invited to the Feast (1973).

|

Every person offered me a smile, said something to make me feel more comfortable, showed me some delicate kindness or forbearance. I’m sure my fear was written on my face — and had been written on the faces of perhaps every volunteer they’d ever seen venture onto that cement walkway. But by the end of the night, I was high-flying with a strange kind of energy, a stirring. I’d been changed.

For the next ten years, I visited The Banquet every chance I could. I went from volunteer to group organizer to children’s coordinator to assistant director. I gave the orientation speech to volunteers and tentatively led them in song. I entered data into the computer and sat with Bill on the back steps when he knocked and asked for an off-hours sandwich.

What I saw, day after day, was in fact my own need. I needed to be there. I needed these people. I needed to chat with them, be welcomed by their gentle teasing and wide smiles, get hugs from the children. I liked to think I was helping, but I couldn’t pretend it was the whole story.

That discovery of my own need was actually the secret. Well known to the founders and organizers was what Gross calls the “mysterious, biblical, guest-host relationship” where a kind of fundamental switch takes place. A volunteer comes to give and leaves almost sheepishly knowing she has received far more than she gave, and that, to her own surprise, she has given from her poverty, not from her surplus. The secret was that we were all the poor, the blind, the crippled, and the lame. For some of us the need was more visible than for others.

I observed, again and again, that I welcomed the stranger in myself — the awkward, frightened, vulnerable me who got a surge of joy when I asked someone if he wanted more mashed potatoes, and he replied with a rousing, “Sure, little lady!”

|

|

Utagawa Yoshikazu, Triptych: Foreigners from the Five Nations Enjoying a Banquet (1861).

|

In Luke 14, Jesus isn’t saying to the Pharisee from whom he is receiving hospitality, “Do good deeds.” He is saying, “You who think you are rich: you are actually poor. You who think you have: you have not. That’s good news. The only way you’ll discover this inner vitality is by inviting the poor to be close to you. Then you will begin to see your own poverty and so begin to live.”

As Jesus cryptically says, the reward isn’t found in material gain. It is found “at the resurrection of the righteous” (Luke 14:14). As I thought about what this could mean, I wondered if maybe the resurrection of the righteous isn’t some event that takes place in an eschatological future. Maybe it’s the life that awakens inside us when we find that our separateness is a delusion, our power is really no power, our resources weren’t ever really ours to begin with.

Maybe it means that in the mystery of God’s realm, we find our own lives handed back to us, wounds and all, with such beauty and honor as we never could have expected. We find our reward buried deep in the mysteries of resurrection and hope. Of receiving and being received.

The Banquet, by the way, celebrated 40 thriving years in May. They serve 16 meals a week in two locations to over 200,000 participants a year.

Weekly Prayer

Teresa of Avila (1515–1582)

Christ has no body but yours,

No hands, no feet on earth but yours,

Yours are the eyes with which he looks

Compassion on this world,

Yours are the feet with which he walks to do good,

Yours are the hands, with which he blesses all the world.

Yours are the hands, yours are the feet,

Yours are the eyes, you are his body.

Christ has no body now but yours,

No hands, no feet on earth but yours,

Yours are the eyes with which he looks

Compassion on this world.

Christ has no body now on earth but yours.Born in Spain, Teresa of Avila (1515-1582) entered a Carmelite convent when she was 18, and later earned a reputation as a mystic, reformer, and writer who experienced divine visions. She founded a convent, and wrote the book The Way of Perfection for her nuns. Other important books by Teresa of Avila include her Autobiography and The Interior Castle.

Amy Frykholm: amy@journeywithjesus.net

Image credits: (1) Artsy; (2) Vanderbilt University Divinity Library; and (3) Harvard Art Museums.