From Our Archives

Debie Thomas, Mary's Song (2020); Liz Milner, Lifting Up the Lowly: Poetry From Prison (2017); Debie Thomas, The Pause Before Yes (2014); Ron Hansen, Nothing Is Too Wonderful To Be True (2011); and Ron Hansen, A Startling Announcement to a Girl from Nazareth (2008).

For Sunday December 24, 2023

Fourth Sunday in Advent

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year B)

2 Samuel 7:1-11, 16

Luke 1:46b-55

Romans 16:25-27

Luke 1:26-38

This Week's Essay

Christians will face many distractions this final week of Advent. The images of war in Gaza are unwatchable. Retailers bombard us with the lie that we can spend our way to happiness. Family gatherings and travel will provoke stress and strain. Therapists will warn us about overload.

For me, one of the biggest challenges to an authentic Christmas faith is sentimentality. What you might call the Hallmark Effect. It's hard not to dote on our "angelic" grandkids in oversized bathrobes and "shepherds" with towels for turbans, like I happily did last Sunday at church. At Christmas, all forms of sentimentality crash into the sheer audacity of the story.

The Christmas Story is a post-modernist's worst nightmare of a Grand Narrative — the stupendous claim that "God was in Christ reconciling the cosmos to himself" (2 Corinthians 5:19). In the epistle this week Paul calls it "the revelation of the mystery that was kept secret for long ages" (Romans 16:25), and similarly a "profound mystery" (Ephesians 5:32).

|

|

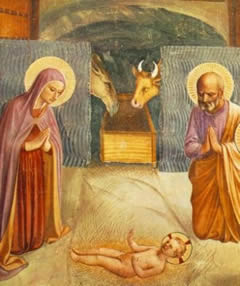

Fresco of the Christ Child, c. 1300, by Fra Angelico.

|

Authentic faith embraces genuine astonishment at such a proclamation, of the sort that appreciates the border lands of disbelief — disbelief in the sense of a contronym. A contronym is a single word that can have contradictory or opposite meanings. In this case, "disbelief" can mean the shock that something is true, or the conclusion that something is false. In the gospel this week, Mary was "much perplexed" by the visitation of the angel Gabriel, but she nonetheless believed the unbelievable.

In his book A Public Faith (2011), the Yale theologian Miroslav Volf tells how the Canadian philosopher Charles Taylor once heard Mother Theresa explain why she served the poor. She often complained, "people say we're social workers. We're not social workers! We're Christians who worship Jesus as Lord and therefore serve people made in the image of God." Taylor, a practicing Catholic, thought to himself: "I could have said that, too!" Upon further reflection, he then wondered, "But could I have meant it?" (emphasis his).

Christmas is the ultimate confession, easy to make with a dash of sentimentality, but with Taylor, I ask myself, "do I mean it?"

|

|

Fresco of the Christ Child, c. 1300, by Giotto.

|

In her book Teaching a Stone to Talk, Annie Dillard lamented how casually we confess our faith: "Does anyone have the foggiest idea of what sort of power we so blithely invoke? Or, as I suspect, does no one believe a word of it? The churches are children playing on the floor with their chemistry sets, mixing up a batch of TNT to kill a Sunday morning. It is madness to wear ladies' straw hats and velvet hats to church; we should all be wearing crash helmets! Ushers should issue life preservers and signal flares; they should lash us to our pews! For the sleeping God may awake someday and take offense, or the waking God may draw us to where we can never return."

Britain's former Poet Laureate John Betjeman (1906–1984), a practicing Anglican (and a very unhappy student under his young tutor CS Lewis at Oxford), held his confessional feet to the intellectual fire. In the first five stanzas of his poem "Christmas," Betjeman describes "sweet and silly Christmas things" like saying "the church looks nice," syrupy greetings like "Merry Christmas to you all!", and "hideous" gifts like bath salts and cheap perfume.

In his last three stanzas, though, Betjeman ups the ante about as high as it can go.

And is it true,

This most tremendous tale of all,

Seen in a stained-glass window's hue,

A Baby in an ox's stall?

The Maker of the stars and sea

Become a Child on earth for me?And is it true? For if it is,

No loving fingers tying strings

Around those tissued fripperies,

The sweet and silly Christmas things,

Bath salts and inexpensive scent

And hideous tie so kindly meant,

No love that in a family dwells,

No carolling in frosty air,

Nor all the steeple-shaking bells

Can with this single Truth compare —

That God was man in Palestine

And lives today in Bread and Wine.

Some people reject the Christmas story as false, observes Kevin Gardner in Faith and Doubt of John Betjeman (2006), even though they might wish it was true. For example, the British writer Julian Barnes didn't believe in God, but he nonetheless admitted that he still misses him. Betjeman, on the other hand, confessed his faith, albeit with candor about the stupendous claim being made.

|

|

Nativity, 1325, by Taddeo Gaddi.

|

The church does many things — intellectual inquiry, moral development, community building, peace-making, interfaith dialogue, hospitals and schools, art, music, and care for the poor. But none of these are unique to the church; you can find them all in many other places. What distinguishes the church from all these other worthy pursuits, as Mother Theresa observed, is our liturgical confession that Jesus the Christ Child is Lord of heaven and earth.

And so every Sunday, to take just one example, our priests raise the bright red gospel book high above their heads as they process down the center aisle of the church. After placing the book on the altar they prostrate themselves before the Mystery. For the gospel reading they repeat the act in reverse, processing back down the aisle into the middle of the congregation, at which point we all stand up and pivot toward the gospel and confess, "Glory to you, Lord Christ!"

|

|

The Birth of Christ, c. 1308, by Duccio di Buoninsegna.

|

If you did that with a volume of Shakespeare people would think you're nuts; and we too are nuts to say what we say at Christmas unless, as Betjeman wrote, we're confessing an "incomparable Truth" that invites us not just to honor Jesus but to bow down and worship him. After considering whether the earliest witnesses were "deceived or deceiving" (Pascal), we all decide whether we too can make that ancient confession.

Matthew's birth narrative describes a series of five dreams to tell this stupendous story. Luke appeals to the Spirit-inspired songs of Mary, Zechariah, and Simeon. John incorporates Greek philosophy about the Logos, connecting creation in Genesis with redemption in Jesus: "In the beginning God created… In the beginning was the Word." What God lovingly created he will assuredly redeem.

This week many of us will sing the Christmas carol “Good Christians All Rejoice,” with its words, “Ox and ass before him bow, and he is in the manger now; Christ is born today! Christ is born today!” But the gospels never mention animals at the manger, even though they became common in the later art and iconography of the nativity. How did they enter the story? What do they signify?

|

|

The Ox and Donkey worship Jesus, 4th century Roman sarcophagus.

|

The earliest mention of animals at the nativity is the Gospel of Pseudo-Matthew from the eighth century: "And on the third day after the birth of our Lord Jesus Christ, Mary went out of the cave, and, entering a stable, placed the child in a manger, and an ox and an ass adored him. Then was fulfilled that which was said by the prophet Isaiah, 'The ox knows his owner, and the ass his master's crib.' Therefore, the animals, the ox and the ass, with him in their midst, incessantly adored him. Then was fulfilled that which was said by Habakkuk the prophet, saying, 'Between two animals you are made manifest.'"

Others credit Saint Francis of Assisi with creating the first manger scene with live animals. Even more interesting is a Christian sarcophagus from fourth-century Rome that depicts an ox and ass worshipping the Christ Child. By the sixteenth-century it's hard to find a manger scene without them. The "incessant adoration" of these brute beasts invites us to make our own confession this Christmas, and with Charles Taylor to consider whether we really mean it.

Weekly Prayer

Aurelius Prudentius (348–413)

Of the Father’s love begotten, ere the worlds began to be,

He is Alpha and Omega, He the source, the ending He,

Of the things that are, that have been,

And that future years shall see, evermore and evermore!At His Word the worlds were framèd; He commanded; it was done:

Heaven and earth and depths of ocean in their threefold order one;

All that grows beneath the shining

Of the moon and burning sun, evermore and evermore!He is found in human fashion, death and sorrow here to know,

That the race of Adam’s children doomed by law to endless woe,

May not henceforth die and perish

In the dreadful gulf below, evermore and evermore!O that birth forever blessèd, when the virgin, full of grace,

By the Holy Ghost conceiving, bare the Savior of our race;

And the Babe, the world’s Redeemer,

First revealed His sacred face, evermore and evermore!This is He Whom seers in old time chanted of with one accord;

Whom the voices of the prophets promised in their faithful word;

Now He shines, the long expected,

Let creation praise its Lord, evermore and evermore!O ye heights of heaven adore Him; angel hosts, His praises sing;

Powers, dominions, bow before Him, and extol our God and King!

Let no tongue on earth be silent,

Every voice in concert sing, evermore and evermore!Righteous judge of souls departed, righteous King of them that live,

On the Father’s throne exalted none in might with Thee may strive;

Who at last in vengeance coming

Sinners from Thy face shalt drive, evermore and evermore!Thee let old men, thee let young men, thee let boys in chorus sing;

Matrons, virgins, little maidens, with glad voices answering:

Let their guileless songs re-echo,

And the heart its music bring, evermore and evermore!Christ, to Thee with God the Father, and, O Holy Ghost, to Thee,

Hymn and chant with high thanksgiving, and unwearied praises be:

Honor, glory, and dominion,

And eternal victory, evermore and evermore!

Dan Clendenin: dan@journeywithjesus.net

Image credits: (1–4) ScriptoriumDaily.com; and (5) Wikipedia.org.