Easter Archives

Debie Thomas, "Risen" (2020); Sara Miles, "How to Be an Evangelist" (2017); Ron Hansen, "Death, Thou Shalt Die" (2014); Rebecca Lyman, "Ours the Cross, the Grave, the Skies" (2011).

For Sunday April 9, 2023

Easter Sunday

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year A)

Acts 10:34–43 or Jeremiah 31:1–6

Psalm 118:1–2, 14–24

Colossians 3:1–4 or Acts 10:34–43

John 20:1–18 or Matthew 28:1–10

This Week's Essay

Michael Fitzpatrick is a lay teacher and preacher in The Episcopal Church. After growing up in the rural northwest, he served over five years in the U. S. Army as a Chaplain's Assistant, including two deployments to Iraq. After completing his military service, Michael has done graduate work in literature and philosophy. He is now finishing his PhD at Stanford University.

Christ is risen! The Lord is risen indeed!

We gather together as one Paschal Church to celebrate God’s triumph in Jesus over death, sin, and destruction. The darkness has been vanquished by our eternal Ruler. This is the day when, in the words of the Exsultet, “all who believe in Christ are delivered from the gloom of sin, and are restored to grace and holiness of life… [W]hen Christ broke the bonds of death and he rose victorious from the grave. . . . [W]hen earth and heaven are joined and man is reconciled to God.” At Easter, we proclaim that the Creator of all things has raised this Jesus from the dead and seated him at the right hand of the Father.

We gather together as the Church to proclaim in one voice that we are a people who have been shaped by a decisive event. The term ‘event’ labels an occurrence in the world that is both irrevocable and, when recognized, transformative. An event happens when something changes that cannot be reversed. The COVID-19 pandemic was a worldwide event. Once the virus got into the general global public, it could not be “put back.” We had to find a way to co-exist with the virus while it spread amongst us.

An event is also transformative for our thought and practice, though only when we recognize the event for what it is. There were plenty of people who tried their best to downplay or ignore COVID-19 altogether. While their stubbornness did not alter the objective reality of the virus, their denial allowed them to preserve some measure of stability. Recognition of an event, on the other hand, produces upheaval in our lives, because we cannot avoid its implications. Our lives will never be the same.

Easter names the Christ event, that sequence of occurrences in which Jesus of Nazareth was judged, crucified, buried, raised from the dead, appeared to his disciples, and ascended into heaven. “Christ is risen” is a declaration that these occurrences are together an act of God, and that once we recognize this event, our lives will be fundamentally altered as well. As declared in 1 Peter, an epistle read during Year A of Eastertide, because of this event, “we who were not even a people are now the people of God” (1 Peter 2.10).

|

|

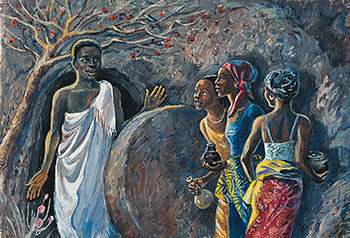

The Empty Tomb, Jesus Mafa.

|

Proclaiming the Resurrection of Jesus is not, however, a matter of proving a fact of history by presenting the relevant evidence. This approach has been popular in the past century, especially in American Christianity. Bestselling books with familiar titles like The Case for Christ and Who Moved the Stone? and Evidence that Demands a Verdict have become commonplace, and each aims to “prove” the Resurrection through historical argument. As a result, plenty of skeptics and progressive Christians doubtful of the Resurrection as a “real” event have published rejoinders expressing their skepticism that anything really happened.

Theologian Sarah Coakley suggests that these efforts, both for and against the historicity of the Resurrection, are misguided. They assume that the Resurrection is a regular fact in the collection of historical facts, available for observation by anyone. Instead, Coakley suggests that encountering the fact of the Resurrection and its reality requires a change within us. Coakley notes that when Jesus appears to his disciples, some recognize him and believe while others only believe later on. Whether we can recognize and acknowledge the Resurrected Jesus depends on our ability to see, on our becoming the kinds of people who can see material bodies as places where God acts. Without the transformation of our minds, no amount of historical evidence will prove (or disprove) that the Christ event happened.

In our Gospel reading from John, Mary is crying outside the tomb of Jesus, weeping that his body is gone and she doesn’t know what has happened to her Lord. At some point she turns around, and there standing before her is the risen Jesus in the flesh. But Mary does not recognize him, not at first. She instead thinks he’s the gardener servicing the surrounding burial grounds. Suspecting he has moved the body, she pleads with Jesus to show her where his body is. Suddenly he shouts her name, and it’s like scales fall from her eyes and she can see clearly. Jesus was the Resurrected One the whole time, but it was only when she had “eyes to see” that she could see Jesus properly.

Celebrating Easter is not like a celebration of an ordinary historical event, like Marie Curie becoming the first female professor at the University of Paris, or the end of apartheid in South Africa. Easter is our act of submission to become people whose minds are being transformed by God to see the risen Christ. In Matthew 28, Jesus meets the female disciples on the road, and they take hold of his feet and worship him. But this happens only after the angel transforms their minds by teaching them that Christ is risen. Nor does Jesus tell them that he will accompany them to Jerusalem to see the other disciples; instead, he instructs the women to tell the male disciples, “Go to Galilee, there they will see me.” The disciples are given time to become people who can see the risen Jesus; the promise is that if they are so transformed, then they will see him.

Wait a moment—surely all of this applies to the early disciples and followers of Jesus and not to us. No matter how much we are transformed, we will not see the risen Christ, right?

|

|

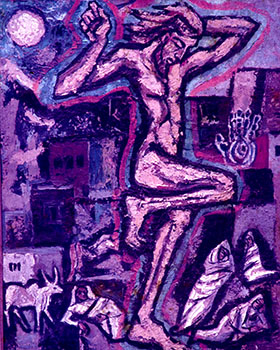

He Who Steps Over—The Tandavan, oil on canvas by Indian artist Jyoti Sahi, 1975.

|

I want to venture the bold claim that just as Jesus promised his disciples would see him when their minds were ready to see the truth of the Resurrection, so we are under the same promise. Christ is risen, and he is here for all to meet. The first disciples experienced Christ risen in the flesh; we know this because Matthew’s text says the women held on to his feet. But that doesn’t mean Christ appears in the flesh to everyone in the exact same way. For the two on the road to Emmaus, Christ appeared at the breaking of bread (they hadn't recognized him either). For St. Paul or St. Stephen, Christ appeared in a theophany from heaven. For us, there are other ways that the resurrected Christ can appear.

The Resurrection is the coincidence of divine act and human life, “a state of affairs in which the material world we know is rendered irreversibly transparent to the eternal act of God,” Rowan Williams writes in his essay “Rethinking Eschatology.” Williams contends that we encounter the resurrected Christ wherever the sacrament of the Eucharist table is fully realized. As the material body of Jesus was put to use by God at the Resurrection, so the bread and wine of the Lord’s Supper become for us the Body and Blood of Jesus. When the consecrated bread is held high over the altar, we are seeing not only the Lamb slain for the sins of the world but also the Resurrected Christ, if only we have eyes to see.

Rowan Williams also identifies Scripture as a locus for encountering the Resurrected One. Scripture is composed of human words, just as Jesus was utterly human through and through. Yet the utterly human words of Scripture are taken up and spoken to the Church as the Word of God heard together in fellowship. Williams writes, “Thus Scripture read in the Church is there as carrying the energy and meaning of the Paschal transformation: all scriptural reading is in some sense ‘about’ the resurrection, since it is about the living communication of Christ, upon whom all the record of God’s dealings with our human world converges.” Sharing the words of Scripture allows us to form a common story and speech around which we have our identity as followers of the Resurrected Christ.

I’d like to suggest a couple other places we can witness the Resurrected Jesus: in our Christian sisters and brothers, and in the poor.

To be transformed by Christ is to become people who can say of our own deeds, “Not I, but Christ living within me” (e.g., Rom. 15.28). When we want to see the Resurrected Christ, we look to each other to see the Resurrected Christ alive within each baptized Christian. The Resurrected Christ can appear in any flesh, and sometimes, Lord willing, is seen by others in our flesh. We cannot doubt the fleshly resurrection of Jesus, for to do so is to doubt whether the Resurrected Christ can take up our flesh, wherein our lives become a coincidence of the divine and the human.

|

|

The Resurrection, oil on canvas by Italian artist Francesco Buoneri, 1620.

|

Jesus also taught that he would appear to us in the least among us. In the poor and downtrodden, we see the Resurrected One who identifies with the most lowly, so as to give them the highest places of honor. If we want to see Jesus in the flesh, we must allow the Holy Spirit to so transform our minds that in the sight of destitute and unwashed bodies savaging for scraps we see the love of God poured forth in Christ.

We pray, receive the blessed Sacrament, hear the proclamation of Scripture, worship in our sanctuaries, confess our sins, serve the needy, and practice the spiritual disciplines because these are the means of the Holy Spirit to transform us into people who can see Christ. It’s not about trying harder, striving to be good, or letting the Resurrected Christ serve as inspiration. Easter is about becoming a new creation, letting God transform us into a different kind of humanity, the kind that has the eyes to see the Resurrected Jesus and let him live through our fleshly bodies as divine action in the world.

When we gather for the Easter Vigil and the great 50 days of feasting in Eastertide, we are coming together to rejoice in the Resurrection, which is not some distant historical event that we’re trusting on the testimony of a few disciples, but a living reality to which we bear witness even now for the sake of a broken and hurting world. Jesus says to us, “There you will see me”—there, in the Holy Communion; there, in the Word of God; there, in the Church proximately gathered; there, in the least among us. This Easter, let us gather to see the Resurrected Christ together, and when we do, take hold of his feet, and worship him.

Christ is risen! The Lord is risen indeed! Alleluia, Alleluia!

Easter Prayer

(translated from the Latin by John Mason Neale, 1851)

Draw nigh and take the Body of the Lord,

and drink the holy Blood for you outpoured.Saved by that Body and that precious Blood,

with souls refreshed, we render thanks to God.Salvation's Giver, Christ, the only Son,

by his dear Cross and Blood the victory won.Offered was he for greatest and for least,

himself the Victim, and himself the Priest.Victims were offered by the law of old,

which in a type this heavenly mystery foretold.He, Ransomer, from death, and Light from shade,

now gives his holy grace his saints to aid;approach ye then with faithful hearts sincere,

and take the safeguard of salvation here.He that in this world rules his saints and shields,

to all believers life eternal yields.With heavenly bread makes them that hunger whole,

gives living waters to the thirsting soul.Alpha and Omega, to whom shall bow

all nations at the Doom, is with us now.

"Sancti venite" was composed at Bangor Abbey in the 7th century AD, making it the oldest known Eucharistic hymn. It was carried to Bobbio Abbey and was first published by Ludovico Antonio Muratori in his Anecdota Latina ex Ambrosianæ Bibliothecæ codicibus (1697–98), when he discovered it in the Biblioteca Ambrosiana. According to a legend recorded in An Leabhar Breac ("The Speckled Book," a medieval Irish vellum manuscript containing Middle Irish and Hiberno-Latin writings), the hymn was first sung by angels at St. Seachnall's Church, Dunshaughlin, after Secundinus had reconciled with his uncle Saint Patrick. -- Adapted from Wikipedia

Michael Fitzpatrick welcomes comments and questions via m.c.fitzpatrick@outlook.com

Image credits: (1) Marist Messenger; (2) Art & Theology; and (3) Wikimedia.org.