From Our Archives

For other essays on this week's texts, see Sr. Nancy Usselmann, FSP, The Spirit Gives Life (2017); and Dan Clendenin, Jesus Raises Lazarus (2014).

For Sunday March 26, 2023

The Fifth Sunday in Lent

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year A)

Ezekiel 37:1–14

Psalm 130

Romans 8:6–11

John 11:1–45

This Week's Essay

This essay was originally posted on March 22, 2020 by Debie Thomas during the Covid pandemic.

Like many of you, I am “sheltering in place” as I write this essay, and battling fear as the news headlines grow darker and grimmer. Here in California, most stores and businesses are closed, medical professionals are facing equipment shortages, the streets are ominously quiet, and the number of Covid-19 cases is growing by the day.

I know that in other parts of the world, doctors are being forced to make horrific decisions about who will receive medical care, and who will die. I know that countless people are getting laid off without warning, facing illness without medical insurance, caring for the infected without adequate protection, watching helplessly as savings drain away, and mourning their dead without the dignity of funerals or memorial services.

Here we are, Church. Here we are in crisis, watching the world reel and lurch in ways most of us have never experienced before. Here we are as the Gospel for this fifth Sunday in Lent shows us Jesus, holding two angry, grief-stricken sisters in his arms, and telling them with absolute certainty that he is the resurrection and the life. Here we are as Jesus holds the triumphant truth of eternal and abundant life in unashamed, unapologetic tension with his own tears.

|

|

The Raising of Lazarus by Duccio di Buoninsegna (1255-1319).

|

I’ll be honest: the story of Jesus raising Lazarus from the dead is a hard one for me. At many levels, I don’t understand it. I don’t understand why Jesus dawdles when he first receives word of Lazarus’s illness. I don’t understand why he allows his friends to suffer for the sake of “God’s glory.” I don’t understand why he tells his disciples that Lazarus is “asleep” rather than dead. I don’t understand why he sidesteps Martha’s tortured accusation: “Lord, if you had been here, my brother would not have died.” I don’t understand why Jesus raises just one man, leaving countless others in their graves. And I don’t understand why Lazarus virtually disappears from the Gospel narrative once his grave clothes fall off. Why is he never heard from again?

In many ways, the story is shrouded in mystery. But today, this week, now, I cling to the two words in the narrative I do understand: “Jesus wept.” Thank God — Jesus wept. For me, this is the heart of the story as we live through the Covid-19 crisis: that grief takes hold of God and breaks him down. That Jesus — the most accurate revelation of the divine we will ever have — stands at the grave of his friend and cries.

Let me be clear: in focusing on Jesus’s tears, I’m not ignoring or miminizing the raising of the dead, the conquering of the grave, the unbinding of the bound. I am a Christian because I believe in resurrection. I believe it as metaphor and as symbol. I believe that God can and will bring back to life all that is dead, buried, forgotten, and festering within us: old wounds, hardened hearts, stubborn addictions, fierce fears. I believe that God is always and everywhere in the business of making us more fully and abundantly alive — alive to love, alive to hope, alive to each other, alive to Creation.

|

|

The Raising of Lazarus, illuminated manuscript, 1504.

|

But I believe in more than that. I also believe in literal resurrection. I believe in life after our physical deaths. I believe that the great, good news of the Gospel is that Jesus actually conquered death — all death, every death, Death itself. For me, the love and compassion of a just God requires the making right of every death humanity has endured, every death that has left us staggering in shock, rage, bewilderment, and grief. For me, our horror in the face of death corresponds to an eternal reality: we were not made for the grave. We shudder because something deep and instinctive within us understands that we were created for life, and we feel robbed when life is taken away. For me, the literal raising of Lazarus is a sign that death will NOT have the last word in our physical, embodied lives. We will be raised.

But I hold these joyful beliefs in a world full of uncertainty and sorrow. A world where Martha’s accusation (“Lord, if you had been here…”) thunders through the ages for its truth and agony. So I cherish Jesus’s tears right now, perhaps even more than I cherish the miracle that follows them. Here are some of the reasons why:

When Jesus weeps, he legitimizes human grief. His brokenness in the face of Mary and Martha’s sorrow negates all forms of Christian triumphalism that leave no room for lament. Yes, resurrection is around the corner, but in this story, the promise of joy doesn’t cancel out the essential work of grief. When Jesus cries, he assures Mary and Martha, not only that their beloved brother is worth crying for, but also that they are worth crying with. Through his tears, Jesus calls all of us into the holy vocation of empathy, co-suffering, and lamentation.

|

|

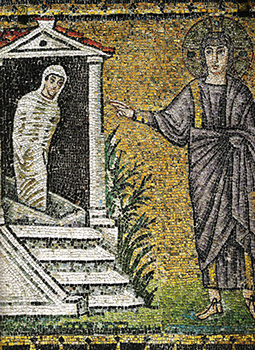

The Raising of Lazarus, sixth-century mosaic, Sant' Apollinare Nuovo, Ravenna, Italy.

|

When Jesus weeps, he honors the complexity of our gains and losses, our sorrows and joys. Raising Lazarus would not bring back the past. It would not cancel out the pain of his final illness, the memory of saying goodbye to a life he loved, or the gaping absence his sisters felt when he died. Whatever joys awaited his family in the future would be layered joys, joys stripped of an earlier innocence. Joys shaped by the sorrows, fears, and losses they’d just endured. In Lazarus’s case, his future would be nothing like his past. Forever afterwards, he’d be known in his village as the One Who Returned. Perhaps that bizarre fact would make him a hero. Perhaps it would make him a pariah. Either way, life would be new and strange and scary. Jesus’s tears honor the reality of human change: he grieves because things will never be the same again.

When Jesus weeps, he respects the necessity of silence, the sanctity of the wordless and the unsayable. We should pay careful attention when the Word himself refuses to speak. Sometimes there is nothing to be said in the face of loss; sometimes tears are our best and most honorable language. We who are religious often rush to words, feeling an urgent need to wrap other people's pain in platitudes, Bible verses, condolences, promises. Through his wordless tears, Jesus cautions us to pause. He shows us that silence, too, is faithful. Sometimes, silence is love.

When Jesus weeps, he honors the nuances of faith. At no point does he expect piety to be disembodied or sanitized. He recognizes that all expressions of belief and trust come with emotional baggage. Martha expresses deep resentment and anger at Jesus’s delay, and in the next breath voices her trust in his power. Mary blames Jesus for Lazarus’s death, but she does so on her knees, in a posture of belief and submission. Likewise, Jesus’s face is wet with tears when he prays to God and resurrects his friend. This is what real faith looks like; it embraces rather than vilifies the full spectrum of human psychology.

|

|

The Resurrection of Lazarus, 12th-13th century, Athens.

|

When Jesus weeps, he acknowledges his own mortality. In John’s Gospel, the raising of Lazarus is the precipitating event that leads to Jesus’s own arrest and crucifixion. When word spreads about the miracle in Bethany, the authorities decide that enough is enough; Jesus must be stopped. Essentially, Jesus trades his life for his friend’s. Given this fact, I imagine that Jesus’s tears are an expression of grief over his own pending death. He knows that the end is imminent, he knows that his time with his friends is almost over, he knows that it’s nearly time to say goodbye to the lakes and skies and hills and stars he loves. In crying, he asserts powerfully that it is okay to yearn for life. It’s okay to cling to this beautiful world. It’s okay to feel a sense of wrongness and injustice in the face of death — death is the enemy, the aberration, the thief. It is okay to mourn the loss of vitality, of intimacy, of longevity. It is okay to love and cherish the gift of life here and now.

And finally, when Jesus weeps, he shows us that sorrow is a powerful catalyst for change. In the story of Lazarus, it is shared lament that leads to transformation. It’s because Jesus experiences the devastation of death that he recognizes the immediate need to restore life. It is his shattering that leads to resurrection. Perhaps Jesus’s tears can provoke us in similar ways. What breaks our hearts? What splits us open in sorrow? What enrages us to the point of breakdown? Can we mobilize into those very spaces, even now as the coronavirus changes our world? Can we work for transformation in our places of devastation? Can our sorrow lead us to justice?

During these last weeks of Lent, as we prepare for Jesus’s own death and resurrection, I hope that Jesus’s tears can keep us tender, open, humble, generous, and brave. I hope his honest expression of sorrow will give us the permisson, the company, and the impetus we need, not only to do the work of grief and healing, but to move with powerful compassion into a world that sorely needs our empathy and our love. Yes, we are in death right now, but we serve a God who calls us to life. Our journey is not to the grave, but through it. The Lord who weeps is also the Lord who resurrects. So we mourn in hope.

Debie Thomas: debie.thomas1@gmail.com

Weekly Prayer

Christina Rossetti (1830–1894)

I have no wit, no words, no tears;

My heart within me like a stone

Is numb’d too much for hopes or fears;

Look right, look left, I dwell alone;

I lift mine eyes, but dimm’d with grief

No everlasting hills I see;

My life is in the falling leaf:

O Jesus, quicken me.My life is like a faded leaf,

My harvest dwindled to a husk:

Truly my life is void and brief

And tedious in the barren dusk;

My life is like a frozen thing,

No bud nor greenness can I see:

Yet rise it shall–the sap of Spring;

O Jesus, rise in me.My life is like a broken bowl,

A broken bowl that cannot hold

One drop of water for my soul

Or cordial in the searching cold;

Cast in the fire the perish’d thing;

Melt and remould it, till it be

A royal cup for Him, my King:

O Jesus, drink of me.Christina Rossetti was an English poet.

Dan Clendenin: dan@journeywithjesus.net

Image credits: (1) Wikimedia.org; (2) Wikipedia.org; (3) Wikipedia.org; and (4) Wikimedia.org.