For Sunday May 2, 2021

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year B)

Acts 8:26-40

Psalm 22:25-31

1 John 4:7-21

John 15:1-8

This week’s lectionary essay focuses on Acts 8:26-40. For a reflection on the Gospel reading, see “Abide,” from the JwJ archives: https://www.journeywithjesus.net/essays/1759-abide

Here’s a question to ask ourselves as we move deeper into the season of Easter: what difference does the resurrection make in the way we live and practice our faith? Is the world of the empty tomb substantially different from the world that came before it, or is Easter a mountaintop experience we briefly enjoy but then leave behind to return to “real” life in the valley?

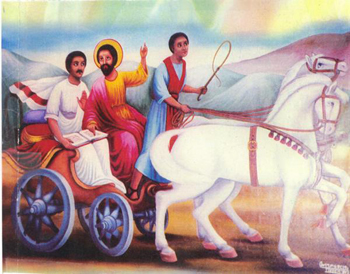

For this fifth Sunday of Easter, the lectionary gives us the story of Philip and the Ethiopian eunuch. As a child, I learned this narrative from the Acts of the Apostles as a one-way conversion story, that is, as the story of one person (Philip, the good evangelist) converting another person (the eunuch, an unsaved sinner). The lesson I took away from the story is that I, too, should share the good news of Jesus as boldly as I can, so that (unacceptable) outsiders might change and become (acceptable) insiders.

I still read Acts 8:26–40 as a conversion story, but what I cherish about it now is the two-way conversion it depicts. Don’t get me wrong; I appreciate the Ethiopian eunuch’s acceptance of the Gospel as Philip shares it, and I don’t for one moment want to diminish the import of his encounter with the Word, both written and incarnate. But I believe we miss some of the beauty and significance of this story if we see Philip merely as a teacher or an evangelist. In my view, Philip is also a student, and what he learns from the eunuch has a great deal to tell us about the life of faith, post-Easter. In his Spirit-led encounter with the Ethiopian official, Philip learns that the resurrection of Jesus changes everything. Everything he knows about insiders and outsiders, piety and depravity, identity and belonging. The eunuch isn’t the only person in the story who undergoes a conversion; the Spirit leads Philip to experience a conversion as well.

The story begins with “the angel of the Lord” directing Philip to a certain "wilderness road" that leads away from Jerusalem. There, on the geographical margins, Philip finds the Ethiopian eunuch, a man who occupies many margins. He is a man interested enough in Israel’s God to make a pilgrimage from Ethiopia to Jerusalem, but according to Hebrew law, he is not free to practice his faith in the Temple (Deuteronomy 23:1). It’s possible that he is a Jew, but in Philip’s eyes, he is a foreigner, a Black man from Africa. He is a man of rank and privilege, a royal official in charge of his queen’s treasury, but he is also a powerless outsider — a queer man who doesn’t fit into the social and sexual paradigms of his time and place. He is wealthy enough to possess a scroll of Isaiah, and literate enough to read it, but he lacks the knowledge, context, and experience to understand what he’s reading.

|

In other words, the unnamed eunuch occupies an in-between space, a liminal space, a space of reversal and surprise that stubbornly resists our tidy categories of belonging and non-belonging. What kind of person, after all, earnestly seeks after a God whose laws prohibit his bodily presence in the Temple? What kind of wealthy, high-ranking official humbly asks a stranger on the road for help with his spiritual life? What kind of long-rejected religious outcast sees a body of water and stops in his tracks because he recognizes first — before Philip, the supposed Christian “expert” — that God is issuing him a gorgeous, unconditional, and irresistible invitation?

I don’t think it’s a coincidence that Philip finds the eunuch reading Isaiah’s description of a silent, suffering lamb. The Word, after all, finds us where we are. It resonates in the deepest, most authentic, and most tender places in our lives. The eunuch lingers over the story of a sheep who is led to slaughter, a lamb who is silent before its shearer, a creature who is humiliated and denied justice as “his life is taken away from the earth.” Perhaps this story calls to him precisely because it describes something of the complexities of his own life, his own religious, sexual, and racial difference, his own vulnerability. What I respect most about Philip in this moment is not that he “evangelizes” the eunuch in some programmatic way — it is that he meets the eunuch exactly where he is, and gently, with the guidance of the Spirit, shows him how his story of silence and resilience, suffering and rejection, belongs squarely within the Story of Jesus.

Yes, the Ethiopian eunuch hears the good news of Jesus’s life, death, and resurrection, and decides to become a follower of Christ. That is true and it is wonderful. But consider for a moment the amazing question he asks Philip in return: “Look, here is water! What is to prevent me from being baptized?” Sit with this for a while as a real question — as a zinger of a question. Ponder it as a dilemma Philip must grapple with as strenuously and as seriously as the eunuch grapples with the life-altering implications of the Gospel.

“What is to prevent me?” What is to prevent me from belonging to the family of God? What is to prevent me from being welcomed as Christ’s own? What is to prevent me from full participation in the risen life and community of Jesus? What is to prevent me from breaking down the entrenched barriers, fences, walls, and obstacles that have kept me at an agonizing arm’s length from the God I yearn for? What is to prevent me from becoming, not merely a hearer of the Good News, but an integral part of the Good News of resurrection?

|

I love the resounding silence that follows the eunuch’s question. Because the silence speaks what words cannot. The silence is thundering, and gorgeous, and seismic, and right. Because the answer to the question is silence. The answer — the only answer — is “nothing.” In the post-resurrection world, in the world where the Spirit of God moves where and how she will, drawing all of creation to herself, in the world where the Word lives to defeat death, alienation, isolation, and fear, there is nothing to prevent a beloved image-bearer of God from entering into the fullness of Christ’s salvation. Nothing whatsoever.

Notice in the text that it is the eunuch who commands the chariot to stop so that he and Philip can make their way to the water. Philip doesn't say a word; he merely obeys the prompting of the man who knows without a doubt that he belongs, that the God he has worshipped from a distance for so long is now doing a new and earth-shattering thing.

Linger here for as long as you can bear to. What is there to say, after all, once the Spirit has spoken?

This is a stunning post-Easter story. If only we, the Church, could find our way into its silence, its answer, its vivid picture of a liberation that leads to the expansive waters of baptism and belonging. But we hesitate, don't we? How long have we pondered the eunuch’s question, worrying over it, theologizing around it, policing its borders because we find the Holy Spirit’s answer too unruly, too frightening? How many barriers have we erected around the font, the communion table, the altar, the Word? How often have we (consciously or unconsciously) communicated the message that those who don’t look, think, worship, live, speak, work, love, and practice like us do not and cannot belong? How many times has the Spirit invited us to a "wilderness road" of faith for an encounter that might convert us to an authentic post-resurrection ethos and hospitality — only to have us resist and turn away?

|

I don’t ask these questions lightly, as if they are without cost or consequence. Because the fact is, if the story of Philip and the Ethiopian eunuch is true, if the post-resurrection world really is a world where all are welcome, then we are going to have to change. A lot. Let’s not kid ourselves: change is hard. Change hurts. Change makes demands on our hearts, minds, lifestyles, and liturgies that we’d rather avoid. But this is the work of conversion. This is the ongoing work of growing in faith. So let’s be consistent. Let’s practice integrity. Let us not demand the hard work of conversion from others when we remain unwilling to engage in it ourselves.

In his beautiful commentary on the book of Acts, theologian Willie James Jennings describes the story of the eunuch this way: “Faith found the water. Faith will always find the water.” The eunuch wanted God as much as God wanted him, so God broke the connection between identity and destiny, between definition and determination. God “inserted a new trajectory.”

The question is not about the wideness of God’s embrace. The question is not about God’s capacity or readiness to lead his beloved ones to baptism. As this story makes abundantly clear, the Spirit will do what the Spirit will do. The only question that remains is whether we’ll participate in the joyful post-resurrection work of God or not. Look, here is water! What is to prevent us from stepping in?

Debie Thomas: debie.thomas1@gmail.com

Image credits: (1) Art and the Lectionary; (2) World Teen; and (3) The Rev. Wil Gafney, Ph.D.