For Sunday June 17, 2018

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year B)

1 Samuel 15:34 — 16:13

Psalm 20

2 Corinthians 5:6-10 (11-13), 14-17

Mark 4:26-34

For the past year, my son has suffered from chronic migraines. He’s missed months of school, and so far, no medical intervention has provided lasting relief. This week, the pain spiked to a point he just couldn’t bear, and he had to be hospitalized. As I’ve sat at his bedside in the pediatric ward over the past couple of days, I’ve asked God all the anguished questions we ask when our loved ones are in pain: “Why? For what purpose? Can you heal? When will this end? Where are you?”

It’s one of those weeks, honestly, when the lectionary feels pointless. At this moment, I couldn’t care less what St. Mark’s Gospel has to say about Jesus, or the Kingdom of God, or anything else; I just want my son’s headaches to go away. It’s during times like this when I realize how pinched and narrow my spiritual imagination continues to be. As it turns out, I have a very specific (and very self-serving) idea of what God’s kingdom and his blessings should look like, and I always take offense when reality comes along and challenges that pristine ideal.

Jesus must have an infuriating sense of humor, though, because the two parables that make up this week’s Gospel reading do precisely that: they take my ideal and turn it upside down. But what is my ideal? If I'm honest, I have to describe it this way: In my perfect version of God’s kingdom, I do A and God does B. Predictably and always. As in, I pray for my son’s healing, and God heals him immediately. In my perfect version, I understand what the heck is going on, at least 95% of the time. In other words, when life gets hard, God at least provides decent answers to the “why?” questions, instead of leaving me to wallow in the unknown.

|

In my perfect version, God makes grand gestures, and does spectacular things. The kingdom isn't commonplace and ordinary; it is straightforwardly miraculous. And in my perfect version, there are clear, inviolable boundaries of what is good and what is bad. Who is in and who is out.

But my ideal is not God’s.

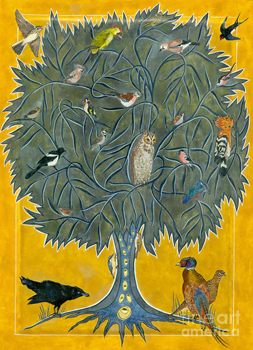

In the first parable Jesus tells in this week’s lection, a gardener scatters seed on the ground, and then goes off to sleep. The seeds fend for themselves (or, as St. Mark puts it, “the earth produces of itself”), and when the grain is ripe, the gardener harvests it. In the second parable, someone sows a tiny mustard seed in the ground, and it grows into a gigantic bush, large enough to offer birds shelter in its branches.

Both of these parables, insofar as they’re meant to show us what the kingdom of God looks like, are ridiculous. They’re big, cosmic jokes. As is the case with all of Jesus’s parables, these are intended to stretch our imaginations far beyond any place we’d take them on our own. Not to keep us comfortable and complacent, but to prod and provoke us into wholly different ways of perceiving and relating to what is sacred. What’s the kingdom of God like? Are you sure you want to know? Okay, brace yourself: the kingdom of God is like a sleeping gardener, mysterious soil, an invasive weed, and a nuisance flock of birds.

Let’s start with the sleeping gardener. If you’re any type of perfectionist, workaholic, neat freak, or compulsive worrier — if you insist on being in control, if you believe in work before play, if you practice vigilance in all things — then you already know what’s wrong with this first parable. Good gardeners don’t toss a bunch of seeds into their backyards and then snooze away the growing season. They plan and plod and hover. They make neat little rows in well-manicured beds. They keep a wary eye on the weather. They protect their gardens from birds, rabbits, and deer. From early spring until harvest, they water, they fertilize, they prune, they weed, and they worry.

|

But the gardener in Jesus’s parable? He scatters and sleeps. He doesn’t slog. He doesn’t micro-manage. He doesn’t second-guess. Like a well-loved infant in his mother’s arms, the gardener enjoys the deep rest that comes from trusting in a process much older, larger, and more reliable than any he might conjure on his own. In this story of the kingdom, it is not our striving, our piety, our doctrinal purity, or our impressive prayers that cause us to grow and thrive in God’s garden. It is God’s grace alone.

Which brings us to the mysterious soil, or St. Mark describes it, the “automatic” earth. According to Jesus’s parable, the kingdom of God is both fecund and hidden, both generous and mysterious. It works its fertile magic underground, deep beneath the surfaces we see and quantify. Yes, the soil eventually brings forth all kinds of abundance, but the process of that bringing forth — all the nitty-gritty details we long to dissect and master — is hidden from our eyes. If anything, we live in the disconcerting time between the planting and the harvest. We look outside, full of hope, and see only dark soil, only vast expanses of uncertainty and delicate potential. As Annie Dillard puts it so beautifully, “Our life is a faint tracing on the surface of mystery.”

In Jesus’s second parable, a sower sows a mustard seed in the ground. The joke here is not only that mustard seeds are tiny, but that the people in Jesus’s day didn't plant mustard seeds. Mustard was a weed — and a noxious, stubborn weed at that. If a 1st century gardener in Palestine were foolish enough to plant it, it would quickly take over his land, dropping seeds everywhere, and breaking down all barriers of separation between itself and the other plants in the garden. Imagine a gardener today planting kudzu, or dandelions, or broomweed. These are commonplace nuisances we try to get rid of, not plants we’d ever cultivate on purpose.

Mustard, moreover, is not a plant that grows with any stateliness or beauty. It’s nothing like a cedar, or a giant sequoia, or even a well-tended rose bush. It grows like a weed, and it looks like one.

So what is Jesus saying when he describes the sacred and the holy as a tiny, insignificant mustard seed? What does it mean to take an invasive, spindly weed — a plant we’d sooner discard than sow — and make it the very heart, the very structural center, of God’s kingdom? Who and what counts in God’s economy? What is beautiful? Who matters? Where do we see the sacred?

The last image in this set of parables is that of nesting birds finding shade in the branches of the mustard plant. It’s a pretty image on its face, but it, too, as it turns out, is a joke: who wants birds taking up residence in their gardens? Birds eat seeds and fruits. They can wreak havoc in a cornfield. Birds are why farmers put up scarecrows.

But Jesus isn't a scarecrow kind of gardener. Why? Because the kingdom of God is all about welcoming the unwelcome. Sheltering the unwanted. Practicing radical inclusion. The garden of God doesn’t exist for itself; it exists to offer hospitality to everyone the world deems unworthy. It exists to attract and to house the very people we’d rather shun.

This is what the kingdom of God looks like. It isn’t what I thought it would be. It doesn’t operate the way I think it should. This is good news, but it isn’t always easy news. The truth is, it hurts to surrender my imagination to God’s expansive, life-changing care. It hurts to trust, to accept mystery, to seek God in the commonplace, and to embrace the unwanted thing as beloved.

For me this week, the challenge is to find God’s kingdom in the midst of my son’s pain. To trust and to wait for the abundance that lies in deep darkness. For all of us, regardless of our circumstances, the challenge remains to scatter seed and rest in God’s grace. To embrace even the weeds, and allow them to become havens of rest. May God help us to do these hard and beautiful things. May God help us to say and to live these words with all sincerity: “Thy Kingdom Come.”

Image credits: (1) FineArtAmerica.com and (2) The Living Pulpit.