Margalynne Armstrong is associate professor of law at Santa Clara University School of Law, where she has taught since 1987.

Dan: Thank you for joining us once again at Journey with Jesus. I say "again" because you were kind enough to contribute a Lenten essay for us back in 2010 (see here).

Margalynne: Thank you for inviting me back. It’s an honor to be included among the thoughtful and productive folks that JwJ has interviewed, and it’s a privilege to be able to speak about race in this forum.

I want to begin with the power of personal story. You bring an unusual background to the many complex questions about race and religion. Please tell us about that.

I was raised in Chicago by a Roman Catholic mother and a father who was not a church-goer. My mom was in charge of our religious upbringing, so we attended Catholic mass but were never baptized in the Catholic Church. Because Chicago under Mayor Richard Daley (the first) was such a Catholic city, even though I went to public school the Catholics were released from school early on Wednesdays to go to catechism at a nearby parochial school. By the time I reached high school my family was only going to church on Easter. So, I grew up thinking I was Catholic, but wasn’t officially. I went to Earlham College, a Quaker institution that I learned about in high school when I was involved with the American Friends Service Committee working on anti-war and education issues. At Earlham I went to Quaker Meeting, and continued to attend Meeting in San Francisco for a few years after I graduated from law school at Berkeley. I met my spouse Andrew at law school. He grew up attending Hebrew school and confirmation, but was never bar mitzvahed because his rabbi found no scriptural support for the ceremony. Andy is decidedly agnostic. After we had our daughter, I decided to raise her as an Episcopalian, primarily because the church ordained women, was welcoming to everyone, including lesbians and gays (at least the churches I knew of), and the services were very recognizable to me from the mass I attended as a child. I attended foundational classes at Grace Cathedral in San Francisco for a year and was baptized there on Easter, twenty five years ago. My daughter and I attended St. Mark’s Episcopal Church in Palo Alto. She now identifies as Jewish, but is very involved in working for the rights of Palestinians.

|

|

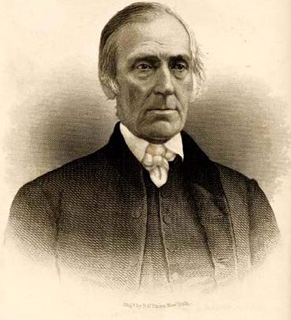

Levi Coffin.

|

You and your husband Andy met at an auspicious time and place of social ferment — the University of California's Berkeley law school in the late 1970s.

Berkeley Law School (then known as Boalt Hall) had a somewhat conservative faculty with a predominantly liberal student body. There were some fairly radical students involved in gay and lesbian rights, diversification of the faculty, and the anti-nuclear movement. I recall a few faculty members who were pretty leftist, but they were the minority. I was actually surprised at how un-radical Berkeley was. And the year I graduated was the year Reagan took office as president, so my class graduated not with a bang, but a whimper.

As a law professor, you've published scholarly articles on racial discrimination, social justice, housing, and teaching about race and privilege. You're well versed in critical race theory. You've spent a lot of time thinking about race and religion.

Well, I think a great deal more about race than religion these days. I’ve been in a pretty secular mode lately, trying to work for and write about social causes that I believe are important. It’s interesting to compare the Black Life Matters movement, which does not operate from within institutions, with the Civil Rights Movement, which was so deeply rooted in Black churches. Not that Black churches aren’t involved, but they’re not the center of BLM leadership.

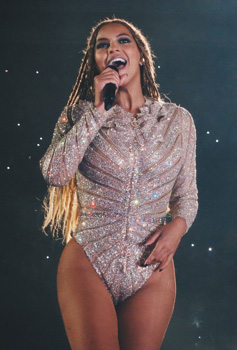

And unlike many intellectuals, you care about popular culture, especially music and cinema. You recently explained to me Beyoncé's use of the racially-charged meme "Becky" in her new album "Lemonade": “He only want me when I’m not there / He better call Becky with the good hair.” It turns out that's a loaded phrase with its own cultural history.

The Becky reference comes out of an old Sir-Mix-A-Lot video in which two white girls, one of whom is named Becky, disparage the behinds of Black women for being too big. So Becky became a slang term for white girls. There's a tradition among Black intellectuals to recognize and write about Black popular culture, which is often simultaneously castigated and appropriated by the larger society. Zora Neale Hurston, Richard Wright, and Claude McKay, leading authors of the Harlem Renaissance, rejected the notion that Black respectability required adopting white culture and suppressing all things Black. Hurston puckishly referred to herself as the Queen of “the Niggerati,”[1] a label she coined for her fellow artists and authors who were honestly examining the experience of being Black Americans. Today, Professor Cornel West writes about and produces rap music, and bell hooks [sic] recently published a critique of Beyoncé’s film and CD "Lemonade" in order to challenge the artist and her audience to move beyond celebrating women’s strength and ability to endure the pain inflicted by patriarchy through “daring to create lives of sustained optimal well-being and joy.”[2] And Professor Henry Louis Gates of Harvard is on public television with his genealogy of the celebrities show, which got very interesting when Ben Affleck asked Gates to hide Affleck’s slave-owning ancestry.

So, you bring a rich mixture of the personal, the popular, the religious, and the intellectual. A rare gift!

Well, I don’t think many Constitutional Law professors use Sir-Mix-A-Lot to help students remember Article I Section 10’s prohibition against granting titles of nobility.

Perfect!

I've been thinking about how misleading it can be to generalize about race for 40 million American Blacks. I just read two very different memoirs by Black authors — Negroland (2015) by Margo Jefferson, who grew up among Chicago's black aristocracy, and Between the World and Me (2015) by Ta-Nehisi Coates, who gives voice to urban rage and despair. To take another example, The Warmth of Other Suns (2010) by Isabel Wilkerson tells three very different stories about Blacks who migrated out of the south, including a surgeon who was not allowed to operate on white people.

Cultural and material diversity among African Americans has always been a fact and is accelerating, just as it is for other Americans. Look, there’s even cultural diversity at the family level. My own social, economic and cultural life is incredibly different from that of my siblings. Three of my siblings have remained in Chicago their entire lives, another brother has lived in Japan, Korea and Florida. I have a graduate degree, one sibling has a G.E.D. My parents came from very different cultural backgrounds, even though they both grew up in segregated border-states. My mom was from St. Louis and became an RN educated in a Catholic nursing school operated by the Sisters of the Holy Family of Nazareth. Her family had no money, but she scraped together enough tuition for one semester. She impressed the sisters so much in that one semester that they gave her a scholarship under the condition that she work at the hospital for a few years after she graduated. My mom was an exceptional student who tutored other students and obtained the highest score on the nursing exam in Illinois after graduation. She worked at that hospital for 15 years. My dad was from rural Tennessee. His father died when my dad was two. His stepfather wanted him to work on the farm rather than go to school, so my father ran away to Chicago to go to high school on his own, and then served in the Army on the mail trains during World War II. He went to Fisk University, a historically Black university in Nashville, on the GI Bill. He came back to Chicago and tried a variety of jobs, including high school teacher. He found success as the publisher of a weekly newspaper for Chicago’s Black community. My parents were both poor Blacks who strived their way into the middle class despite both legally imposed and de facto segregation. Contemporary America imposes fewer racial restraints, and allows for infinite diversity in infinite combinations across the board.

Jefferson writes about a "hyper-conscious identity" or a "double consciousness" as a "third race" that was foreign to a Black church friend of mine. My friend says she was well aware of racial issues growing up, but not obsessed by them.

That concept of double or multiple consciousness has been examined by Critical Race Theorists since the 1980s. If you’re in the Black middle class or a professional who works in predominantly white environments, and then return home to segregated neighborhoods, you’re going to use a different language at home and at work. It’s probably true for everyone, but the degree of difference between the familiar and the formal worlds can be more pronounced for minorities. Ask yourself how different is the language you use at home from that you use on the street or at the office. NPR had a series in 2013 about “Code Switching,”[3] and the different voices and identities many people of color use depending on where they are. By the way, Beyoncé figures prominently on the site.

So, describing the "black experience" is a conversation that takes place not just between blacks and whites, but very much within the black community itself — with all manner of complexity and controversy.

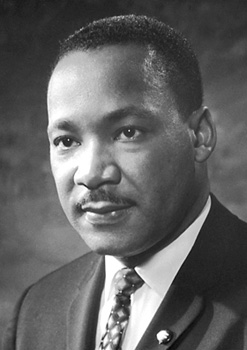

Yes, but there are commonalities that are often imposed on Blacks by society or certain segments of society. One of these commonalities is the uncertainty that arises in encounters with police. It doesn’t matter what an individual African American’s economic or social story is, some police officers, or entire police forces like that in Chicago, approach Blacks as dangerous or as having "violent tendencies,” to quote the remark made by an Austin police officer to a 112 pound elementary female school teacher who he flung to the ground twice[4]. Racial discrimination has no regard for an individual’s personal attributes. People who discriminate endow those they encounter with preconceived negative ideas that are based on notions or people that are completely external to the interaction. In “Letter from a Birmingham Jail,” Dr. King paraphrases Martin Buber: “Segregation substitutes an 'I-it' relationship for an 'I-thou' relationship and ends up relegating persons to the status of things.” Thus, a commonality for Blacks in America is the possibility of random relegation to a degraded status by agents of the state who are ignoring that they are sworn to protect the public, including Black people.

|

|

Martin Luther King, Jr.

|

Eugene Robinson of the Washington Post has argued for greater nuance. In his book Disintegration: The Splintering of Black America (2010), he says that it's misleading to speak of a monolithic black America with a single interpretive narrative. Robinson proposes that black America has fragmented into four different groups that are "increasingly distinct, separated by demography, geography, and psychology. They have different profiles, different mind-sets, different hopes, fears, and dreams." In Robinson's taxonomy, there's a huge black middle class, transcendents like Oprah and Obama, emergents (immigrants from Africa and the Caribbean, and then blacks in biracial marriages), and what he calls the abandoned.

Yes, it's clearly true that there are very different statuses among Black Americans, but until we are presumed by governmental authorities to have the same rights, and deserving of the same treatment as other Americans, these differences can disappear in an instant. Look at the numerous articles that describe how Blacks from all backgrounds are subject to frequent police stops and detention. Recently, Dr. Dre was handcuffed by police at his Malibu home after he was falsely accused of brandishing a gun by someone who followed him home in a road rage incident. Dre, who is fairly reclusive, was originally a rapper in NWA, but is now known for the sale of his popular high end Beats headphones to Apple for a reputed three billion dollars. There’s a scene in the film “Straight Outta Compton” where the police force the members of NWA to the ground, when the group is taking a break outside of their recording studio. Thirty years and billions of dollars later, he’s still presumed to be a criminal by the police.

I also remember the infamous incident when the Harvard professor Henry Louis Gates was arrested by local police as he entered his own home.

Yes, President Obama commented that the police officer acted “stupidly,” and media focus shifted to the President, criticizing his “anti-police rhetoric.” The incident terminated in a “beer summit” in the White House. The incident was pretty dismaying. People don’t even recognize their neighbors anymore and police can’t just ask for an i.d. It’s really important for there to be police training on a nationwide level on de-escalation.

Despite the importance of nuance, it's not like we can't identify broad and important socio-economic trends, like the mass incarceration of Black men, described by Michelle Alexander in The New Jim Crow (2010). She argues that "mass incarceration in the United States has emerged as a stunningly comprehensive and well-disguised system of racialized social control that functions in a manner strikingly similar to Jim Crow." In her view, our penal system isn't broken, it's working just as it was designed.

Around the time that mass incarceration began, unionized industrial jobs were in decline. A lot of people who were put out of work, or their adult children, could turn to the carceral sector to find jobs that paid as well as the ones that had dried up. From slavery, to Jim Crow, to mass incarceration, Black subjugation has provided huge economic benefit to the White majority and a few Blacks. Slavery directly exploited labor, Jim Crow excluded Black Americans from profitable jobs and property ownership, and mass incarceration restrains Black bodies to produce income, based on drug policies that arise from decisions our society did not have to make. The current move to legalize recreational marijuana illustrates just how volitional mass incarceration was and is.

Or to take another example, we now appreciate the importance not just of overt racism, but also of unconscious biases. We had a forum on this in our church.

Yes, but it’s really important to understand that bias can be overcome or minimized. Although bias is a part of how we process information, it’s learned and can be unlearned.

So, unconscious bias might be an explanation, but we shouldn't use it as an excuse.

Exactly, recognizing the existence and prevalence of unconscious bias is great, but it’s just a first step.

Down through the centuries, much of the white church has supported racist policies and practices.

It's a sad history. You should see some of the letters written by church leaders, including Episcopalians, that opposed abolition and later desegregation. Pretty shameful stuff.

There have been some notable exceptions, like abolitionist Quakers in 17th-century England and the United States, and Wilberforce, the Clapham Sect, and Methodists in 19th-century England. In the American civil rights movement, Will Campbell and Daniel Berrigan come to mind.

One of the reasons I went to Earlham was because of its connections to Levi Coffin, a Quaker who was a prominent leader of the Underground Railroad Movement. His home had many concealed rooms and was a major stop for approximately one hundred escaping slaves every year until the Civil War. When the Religious Society of Friends advised its members to cease participating in the abolitionist movement, Coffin formed the Antislavery Friends. Unfortunately for me, the Earlham community was probably the one that threw out Coffin; it was more conservative than I had expected it to be.

There are also Scriptures in both the Hebrew Old Testament and Christian New Testament that, upon a simple or simplistic reading, support slavery. Which brings us to one of the most counter-intuitive facts of their 500-year history in North America — that African Americans adopted the Christianity of their white oppressors.

Slavery in both the Christian and Islamic traditions was supposed to end upon the slaves’s conversion to the faith. Conversion was the moral justification for slavery. In the new world, that pretense was quickly abandoned, but most slave owners felt some obligation to promote Christianity. I think that religion offered enslaved Blacks some of the little respite available from forced labor and imposed ignorance. And Black Christianity was infused with African worship traditions, particularly in the Catholic Church.

|

|

Beyoncé.

|

You might argue that the Black church is the most resilient and important social institution in the African American community.

It’s interesting that the African American millennials are more likely to attend church than White millennials, and are as likely to attend as Black Baby Boomers. But I have no particular insight about Black churches, having grown up Catholic. The first parish my family attended was predominantly black, but when we moved to Hyde Park the church was mixed race, but predominantly white. So, I’m no expert on the Black church as a site of worship. But I grew up seeing the Black church as leading the movement for racial equality. On Saturday mornings, I often went with my dad to the Operation Breadbasket meetings that were led by Rev. Jesse Jackson and other leaders from the Black Church. Later known as Operation PUSH (People United to Save Humanity), and now as Rainbow/PUSH Coalition, Operation Breadbasket was at the center of the civil rights movement in Chicago, working for equal opportunity in employment, residential access, education and politics. At the end of the meetings, I had to sell newspapers outside — and remember that around 1967 I was competing with folks who were selling the Black Panther newspaper. Although my exposure has been to the activism and protest components of Black protestant churches, one of the most profoundly spiritual moments in my life was when I visited Atlanta about ten years ago and sat in the original Ebeneezer Baptist Church listening to a recording of one of Dr. King’s sermons. I sat with my eyes closed and felt as if I had moved through time to be touched by Dr. King’s faith and strength.

After forty years on the front lines of questions about race and religion, do you find yourself more encouraged, or discouraged, about American culture in general and the church in particular?

In some ways I’m encouraged. I just wrote an article about America’s history of impunity for killing Black people. Over time, fewer and fewer people have a legal right to kill Blacks without incurring punishment. I think the Black Lives Matter movement is trying to remove impunity for police killings of all civilians. In the end, this will benefit everyone. But I despair at the proliferation of firearms, particularly those that are capable of killing dozens of people in just a few minutes. I also despair at the seeming indifference to life demonstrated in Chicago and other places where Black lives are being extinguished by other Blacks in a hideous demonstration of ingrained futility. There has to be educational parity in this country, and people have to have a reason to believe in their own future and potential. Right now, too many young people of color don’t think about or have faith in a tomorrow. Some of these people find religion in twenty years of prison, but they have nothing to come back to. I wish our country cared more about solving these problems. But social justice isn’t cost free, and when money is tight, it’s easily given up. I’ve seen it happen at the law school where I teach, and it seems so contrary for a Jesuit institution. But if the religious and educational sectors aren't supporting social justice, the public sector isn’t likely to expend resources on our most impoverished communities. So, yes, there are also reasons for discouragement.

I recently watched the PBS movie "The Black Panthers" (2016) that commemorated the 50th-anniversary of that movement — which began in 1966 as a neighborhood watch group to monitor police brutality. And here we are today, still fighting that same problem. There are also reasons for optimism — civil rights legislation, desegregated schools, affirmative action, a black president for whom 43% of white Americans voted. In 1983, Ronald Reagan (!) signed into law Martin Luther King Day as a federal holiday. There's a new generation of black politicians like Corey Booker and Deval Patrick. Harriet Tubman will replace Andrew Jackson on our $20 bill, along with other abolitionists like Sojourner Truth on other bills.

We need to keep working for fairness and justice that we probably won’t live to see. But I’m encouraged by the activism and creativity of the young people in the millennial generation. This notion of disruption is the ability to see the world as it should be and to discard or even crush the things that impede that vision. Our world cannot continue in a business as usual mode. I don’t think our children will let that happen.

For further reflection: In addition to the books mentioned in the interview, see the following. The hotlinks take you to our JwJ book reviews.

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Americanah: A Novel (2013).

Lerone Bennett, Before the Mayflower; A History of Black America (1962).

Bertice Berry, The Ties That Bind; A Memoir of Race, Memory, and Redemption (2009).

Devon W. Carbado and Donald Weise, editors, The Long Walk to Freedom; Runaway Slave Narratives (2012).

Adam Hochschild, Bury the Chains; Prophets and Rebels in the Fight to Free an Empire's Slaves (2005).

Gwen Ifill, The Breakthrough; Politics and Race in the Age of Obama (2009).

James W. Loewen, Sundown Towns (2005).

Beverly Lowry, Harriet Tubman, A Biography (2007).

Manning Marable, Malcolm X; A Life of Reinvention (2011).

Mark Noll, The Civil War as a Theological Crisis (2006).

David S. Reynolds, Mightier Than the Sword; "Uncle Tom's Cabin" and the Battle for America (2011).

Randy J. Sparks, Where The Negroes Are Masters; An African Port in the Era of the Slave Trade (2014).

Charles Henry Rowell, editor, Angles of Ascent; A Norton Anthology of Contemporary African American Poetry (2013).

Jeanne Theoharis, The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks (2013).

Without Sanctuary; Lynching Photography in America, with introductory essays by James Allen, Hilton Als, Congressman John Lewis, and Leon F. Litwack (2000).

[2] bell hooks, Moving Beyond Pain, http://www.bellhooksinstitute.com/blog/2016/5/9/moving-beyond-pain

[3] http://www.npr.org/sections/codeswitch/2013/04/08/176064688/how-code-switching-explains-the-world