A Repentant Sinner or a Hidden Saint?

The Story of Zacchaeus

For Sunday November 3, 2013

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year C)

Habakkuk 1:1–4; 2:1–4 or Isaiah 1:10–18

Psalm 119:137–144 or Psalm 32:1–7

2 Thessalonians 1:1–4, 11–12

Luke 19:1–10

I don't know if you'll celebrate Halloween this week — All Hallow's ( 'holy') Eve on October 31, but I hope you'll remember All Saints Day on November 1. The gospel this week about Zacchaeus provides us with the perfect story to do so. But as is so often the case with Jesus, he messes with our assumptions about saints and sinners.

The story of Zacchaeus occurs only in Luke. It comes at the end of Luke's "travel narrative" that begins in Luke 9:51 in Galilee: "When the days drew near for Jesus to be taken up, he set his face to go to Jerusalem." Luke repeats himself at least eight times in this narrative, saying that Jesus is heading inexorably to Jerusalem. The journey ends when Jesus enters Jerusalem, where Luke says that "every day he was teaching at the temple" (19:47).

|

Zacchaeus by Joel Whitehead. |

The name Zacchaeus means righteous, which is pure irony in this story. Luke describes him as the sort of sleazeball person that we love to hate. He says that Zacchaeus was a "chief tax collector." That is, he was a Jew who collected taxes for the Roman oppressors. So he was a traitor to the political cause.

Luke also says that Zacchaeus was wealthy. And surprise, surprise, how did a Roman tax collector get wealthy? By extortion and embezzlement. By taking advantage of the elderly, by exploiting the working poor, and by taking care of his cronies. There's an unspoken assumption of corruption here. Zacchaeus is a man who deserves our disdain.

Zacchaeus was not only corrupt and rich, he was short. When Jesus passed through Jericho, he was eager to get a look, so he did something utterly undignified for a man of his station. He ran ahead of the crowd, climbed up into a tree, then waited for Jesus to pass by. Imagine a powerful lobbyist in Washington doing something similar during a presidential parade.

When Jesus reached that spot, he looked up, saw Zacchaeus, and told him to come down. He then invited himself to stay with Zacchaeus: "I must stay at your house today." And so Zacchaeus climbed down and "welcomed Jesus gladly."

|

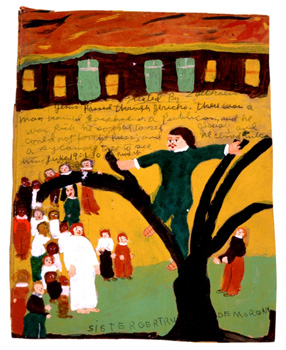

Jesus greets Zacchaeus by Sister Gertrude. |

The response of the crowd was predictable. Luke says that "they began to mutter. 'He has gone to be the guest of a sinner.'"

Luke has returned here to one of his major themes, that Jesus "welcomes sinners" (15:2), which theme was the occasion for his three earlier stories about a lost sheep, a lost coin, and a lost prodigal son. Indeed, "the son of man has come to seek and to save that which is lost."

And so Zacchaeus defends himself before the hostile crowd. He says that he'll give half of his possessions to the poor, and that he'll repay fourfold all the people that he's cheated. That would be a long list of angry tax payers.

Read in this way, Zacchaeus is a sinner who repents and is converted on the spot. He promises future reparations.

But there's another way to read this story in which Zacchaeus isn't a sinner who converts but a saint who surprises. He doesn't make promises about the future, rather, he defends himself and shocks the crowd by appealing to his past.

Both interpretations depend on how you translate Luke 19:8, and in particular the verbs that in the Greek text are in the present tense. It's a good example of the interplay between translation and interpretation.

|

Jesus and Zacchaeus by Soichi Watanabe. |

Even though the verbs are in the present tense, the typical way of reading of this story follows scholars like Robert Stein and translations like the NRSV and NIV. They render the present tense verbs as a "futuristic present." That is, Zacchaeus the sinner repents and vows that henceforth he'll make restitution.

The second option follows commentators like Joseph Fitzmyer and translations like the KJV and RSV. They render the verbs as a "progressive present tense." In this reading, Zacchaeus is a hidden saint about whom people have made all sorts of false assumptions about his corruption. And so he defends himself: "Lord, I always give half of my wealth to the poor, and whenever I discover any fraud or discrepancy I always make a fourfold restitution."

The crowd had demonized Zacchaeus. Jesus praises him as "a son of Abraham."

I like the second reading. It fits with the many times that Jesus calls out good people who are bad and commends bad people who are good.

Luke has already mentioned several unlikely heroes — the faith of a Roman soldier, a "good" Samaritan, a shrewd manager who was commended for his dishonesty, a Samaritan leper who was the only person to give thanks for his healing, and a tax collector (!) who was commended as more righteous than a sanctimonious Pharisee.

So maybe the story is not about a sinner who shocks us by repenting, but about the crowd that demonizes a person it doesn't doesn't like with all sorts of false assumptions.

|

Zacchaeus welcomes Jesus. |

The Episcopal priest Elizabeth Kaeton notes the several ironies here. The despicable Zacchaeus is the generous one. The traditional interpretation that Zacchaeus is a sinner who's converted "tricks us into committing the very sin that the story condemns. It presents Zacchaeus not as a righteous and generous man who is wrongly scorned by his prejudiced neighbors, but as the story of a penitent sinner."

"Turns out," says Kaeton, that "Zacchaeus does live up to his name. He is, in fact, 'the righteous one.' Turns out, Jesus knew that all along!"

Kaeton thus concludes with a nod to Halloween: "Jesus is once again turning our world upside down, confronting us with our assumptions about who is good and who is evil and demonstrating for us the tricks we play in our minds before we treat one another — one way or another. Like the crowd murmuring about Zacchaeus, it is easy to be blinded by our prejudice of 'those people' and find ourselves accusing the very person or people we should be emulating."

Image credits: (1) Edmond Manning blog; (2) KnowLA.org; (3) Dwelling in the Word blog; and (4) Religion-cults.com.