Renunciation and Return:

To Be Fully Known and Freely Loved

For Sunday April 18, 2010

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year C)

Acts 9:1–6, (7–20)

Psalm 30

Revelation 5:11–14

John 21:1–19

A few weeks ago I read the little book by Elie Wiesel called Rashi (2009), about the life and work of Solomon ben Isaac (Rabbi Shlomo Yitzhaki), later known by the shortened Rashi. Rashi was born around 1040 in Troyes, France; he died in 1105. Legends surround his birth and early years, and much is left to conjecture, but after studies in Germany Rashi returned to Troyes and became the intellectual and spiritual leader of the Jewish community there of about 100 families. His commentary on the Bible (1475) was the first book to be printed in Hebrew.

Wiesel observes that Rashi was fifty-five when Pope Urban II issued his call for the First Crusade on November 27, 1095. Jews in Troyes faired better than many, but in other parts of Europe they faced forced conversions or slaughter. An interesting question arose for Jewish leaders like Rashi: should a Jew who "voluntarily" converted to Christianity but then wanted to return to Judaism be received?

|

Judas betrays Jesus. |

Christians have had to answer this same question — how should we deal with our own doubters, deniers, traitors and betrayers who've confessed Jesus as Lord? How should the church treat ministerial failure and moral fault? To preserve its purity and integrity should it purge itself of such failures? Or should it forgive and forget in the name of love? Jimmy Swaggart, Jim Bakker, and Ted Haggard weren't the first or last to provoke this question; the controversy stretches back to the early persecutions of Christians under the Roman emperors and even to this week's lectionary readings.

Some Christians were persecuted at the personal whim of a psychopath like Nero. When a fire broke out in Rome on June 18, AD 64 and destroyed about half of the city, Nero blamed the Christians. In his Annals the Roman historian Tacitus (55–117) writes that Nero punished the Christians with "refined cruelty." Before killing the Christians, says Tacitus, Nero "amused the people" with sadistic tortures: "Some were dressed in furs, to be killed by dogs. Others were crucified. Still others were set on fire early in the night, so that they might illumine it. Nero opened his own garden for these shows, and in the circus he himself became a spectacle, for he mingled with the people dressed as a charioteer."

Other persecutions resulted from systematic state policy. Under Decius (249–251) Christians faced a horrible choice — should they obey the imperial decree to offer sacrifices to the Roman gods and burn incense before a statue of the emperor, or refuse and suffer the consequences? Should they deny their faith in order to live?

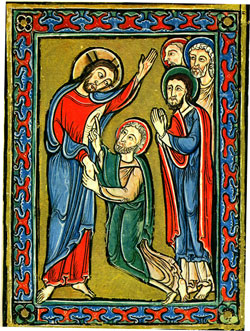

|

Doubting Thomas touches Jesus. |

The last and most severe persecutions came under Diocletian (303–305). In his book Ecclesiastical History Eusebius records the edict that Diocletian issued on February 24, 303: “It was enacted that the meetings of the Christians should be abolished, churches be razed to the ground, that the Scriptures be destroyed by fire, that those holding office be deposed and they of their household deprived of freedom, if they persisted in their profession of Christianity.” In 304 another edict required citizens to burn incense to state idols.

The early believers responded to these trials and temptations in different ways. Some Christians genuinely renounced their faith. Others recanted but did so with their fingers crossed, so to speak. Some believers tried to hide. Cyprian, the bishop of Carthage in North Africa, fled. If you had money or connections, a pagan friend might have provided you with a libellus, a certificate that verified you had obeyed the imperial decree. Some Christians relinquished their Bibles and religious relics to civil authorities to be burned in public bonfires. Then there were the traditors (literally, "those who had handed over"), a technical term for those who betrayed fellow Christians to the Roman government by providing names and addresses.

Those saints treaded a thin line between cowardice and wisdom, failure and fortitude. There were many heroes and martyrs in those days whose bravery inspires and challenges us today1

Peter denies Jesus, 17th century Ethiopia. |

There were also many Christians in those days who failed the faith, in greater or lesser degree, for a whole range of reasons — weakness, fear, deception, stupidity, rationalization, cooperation, and self-preservation. They forced the church to address very practical questions that resonate down to today. When Constantine declared Christianity a legal religion, for example, some believers who had renounced their faith wanted to return to full church communion. Some lapsed priests re-entered positions of clerical authority.

What was to be done? Had the traditors committed unforgivable sins? Could someone who had publicly renounced their faith truly repent? How should the church care for Christians struggling with shame, blame, regret, and self-recrimination? Were the sacraments performed by fallen priests invalid, or was genuine ministry independent of the holiness of the minister? What are the implications of the obvious truth that no one lives a blameless life?

I find it a very uncomfortable exercise to place myself in the shoes of those ancient believers and wonder how I would have responded.

In this week's Gospel of John Peter is eating breakfast on the shores of the Sea of Galilee with the resurrected Jesus. Dirty, wet and tired from fishing all night, he huddled around a "fire of burning coals" (21:9). As he extended the palms of his hands to warm himself before the crackling fire, Jesus asked Peter not once but three times, "Peter, do you really love me?" Three times Peter responded, "Yes, Lord, you know that I love you."

John writes that "Peter was hurt" (21:17) by Jesus's query. The triple question evoked a deeply painful memory for him — the last time he stood around a campfire just a few days earlier he had denied three times that he even knew Jesus (John 18:18, Luke 22:55). But Jesus then reinstated Peter three times with the words, "Feed my sheep," and he went on to become the movement's leader.

|

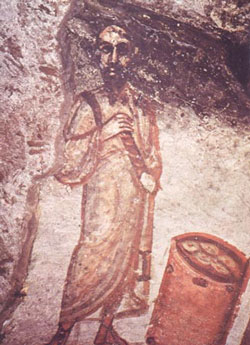

Paul with scrolls, 4th century. |

Similarly, this week's reading from the book of Acts tells the story of Paul's Damascus road conversion. It's a story of how the greatest persecutor of the church became its greatest propagator, eventually traveling over 10,000 miles to spread the good news before dying a martyr's death in Rome. Before his conversion Paul was the consummate traditor, "breathing out murderous threats" and aggressively seeking to imprison believers.

Years later as an old man he wrote a letter to his young protege Timothy. Even in those later years he remembered his sordid past to Timothy with remarkable candor: "I was once a blasphemer and a persecutor and a violent man." He considered himself "the worst of sinners" (1 Timothy 1:13). But like Peter, Paul also transcended his past, "forgetting what is behind and straining toward what is ahead, I press on toward the goal to win the prize for which God has called me heavenward" (Philippians 3:13–14).

Peter, Paul and traditors of every sort remind us that some of the most prominent people in God's story of redemption experienced extraordinary failure, but moved beyond it to become the people that God called them to be. Moses was a murderer, Jacob and Esau were conniving rascals from a dysfunctional family, and King David was an adulterer who murdered his lover's husband.

These people became “successful failures.” They were fully known by God but nevertheless still freely loved. They experienced the liberating truth that "the person who has come to know the weakness of human nature has gained experience of divine power. Such a person never belittles anyone, for he knows that God is like a good and loving physician who heals with individual treatment each of us who is trying to make progress" (St. Maximos the Confessor, seventh century).

For further reflection:

* Cf. Martin Luther, "If you are a preacher of grace, then preach true grace and not a fictitious grace. If grace is true, then you must bear a true and not fictitious sin. God does not save people who are merely fictitious sinners."

* How have you dealt with personal failure?

* From this week's Psalm 30:11: "You turned my wailing into dancing; you removed my sackcloth and clothed me with joy."

* See Henri Nouwen, In the Name of Jesus, which explores John 21 and Peter's reinstatement.

[1] See the early Christian literature like The Martyrdom of Ignatius under Trajan (98–117), The Martyrdom of Polycarp under Pius (138–161) and The Martyrdoms of Saints Perpetua and Felicitas under Severus (193–211)].

Image credits: (1) Christian Theological Seminary; (2) Op. cit.. (3) Middlebury College; and (4) Prof. Brad Starr, California State University Fullerton.