|

Family Values, Biblical Style

For Sunday July 13, 2008

Lectionary

Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year A)

Genesis 25:19–34

or Isaiah 55:10–13

Psalm 119:105–112

or Psalm 65:1–13

Romans 8:1–11

Matthew 13:1–9, 18–23

|

The birth of Esau and Jacob, Master of Jean de Mandeville, French, Paris, about 1360–1370. |

Since my maternal grandmother Hildred was an identical twin, and my nieces Rachel and Rebecca are fraternal twins, my mind gravitated this week toward the Genesis 25 story about the most famous twins in the Bible, Jacob and Esau. I don't normally anticipate a case history of infertility, obstetrics, genealogy, wills, and family dysfunction when I read the "holy" Bible. Reading this Genesis story feels like walking into a county court house and sifting through a musty box of birth, marriage and death certificates, public records of lawsuits born of family pathology, and resentful letters never meant to be read by others. But these are the people, places and problems through which God worked our redemption.

Both Sarah and her daughter-in-law Rebekah suffered from infertility. I don't know the figures for ancient Palestine, but according to the American Society of Reproductive Medicine, about 10% of the reproductive age population in the United States suffers infertility (affecting men and women equally). Multiple births are even more rare. Twins occur in about 1 out of 80 pregnancies, and roughly 3% of live births. Triplets, like my son's good friends across the street from us, occur in about 1 of 8,000 pregnancies, and about 1.8 per 1,000 live births. Statistical improbabilities in biology are also the stuff of our redemption.

Whether ancient or modern, infertility is a tragedy for those who experience it. You don't normally expect good things to materialize out of infertility. Infertility, I suspect, feels like the absence of divine activity rather than its presence, but the story for this week reminds us that such a conclusion is not necessarily true. Human loss and powerlessness are likewise components of redemption. And while multiple births bring special blessings, they pose unique challenges. Can you ever treat "identical" kids equally? Should you even try? How can such genetically similar people be so different? Statistically-speaking, both infertility and multiple births are uncommon, but that's precisely how God acted in the lives of Isaac and Rebekah with the birth of the fraternal twins Jacob and Esau.

The Genesis story about Abraham's extended family encompasses roughly 50 people, almost all of whom are male because females in that time and place did not count, literally or figuratively, as they rightly do today. I suspect that if you drew a family radius that reached to your fifty closest relatives, your story would include the colorful in-laws and outlaws, the strained relationships, that we read about here. It's not all pretty, and hardly the stuff of a Hallmark greeting card, but it's definitely the story of God's saving activity.

|

Jacob receives Esau's blessing, anonymous Flemish tapestery, early 16th century |

Abraham fathered at least eight sons by three women. We know of Ishmael and his mother the Egyptian slave Hagar, and of Isaac who was born to Sarah. This week we read that after Sarah died, Abraham married Keturah, with whom he fathered six more sons. For some unknown reason, the genealogist of the "book of records" (so it's called in Genesis 5:1) names all six of Keturah's sons, but then identifies the offspring of just two of those six (Abraham's grand children), and then, finally, tells us how just one of those two grand sons gave birth to three clans (Abraham's great grand children). This is a spotty record that feels patchy, random and incomplete, glaring with significant gaps. Surely there were some daughters born who remain lost to history? Nor does the record-keeper comment on any of its significance, if it had any significance. Details about Keturah's sons with Abraham sputter out in a genealogical dead end.

We do learn one little dirty detail. Upon his death, "Abraham left everything he owned to Isaac" (Genesis 25:5). While he was living he patronized "the sons of his concubines" (not the concubines themselves, mind you) with a few trinkets, after which he "sent them away from his son Isaac." So much for maintaining warm family relations. Abraham actively disinherited seven of his eight sons and their families, and then banished them. It's hard to imagine a better way to perpetuate family animosities.

Similarly, we learn precious little about Ishmael, the one son born to Abraham and Hagar. Ishmael fathered twelve sons (and maybe some unmentioned daughters?), and the chronicler lists each of their names. He adds that Ishmael died, and then the ominous observation that "they lived in hostility toward all their brothers." Given how Abraham disenfranchised most of his offspring when he disposed of his massive wealth, and how Sarah and Hagar bickered jealously from the beginning, I suppose sibling rivalry is what we might have expected, along with effectively erasing you from the written record of family history.

|

Isaac rejects Esau, Giotto di Bondone, 1290's. |

That brings us to the infertile couple Isaac and Rebekah, and the birth of their famous twins Jacob and Esau. During Rebekah's pregnancy the twins "jostled each other within her," like some harbinger of further family feuding. In a reversal of that culture's conventional wisdom, God announced that the older boy would serve the younger. From birth the fraternal twins were different. Esau was born rough and ready, a hairy boy who grew up to be a rugged hunter who loved the open country. Jacob "was a quiet man, staying among the tents." We find him cooking in the kitchen with the women (25:29). Aggravating these differences, the parents played favorites, Isaac favoring Esau, and Rebekah doting upon Jacob. Jacob eventually conned his brother Esau of the family birthright, which under normal Semitic conditions gave the bearer a double share of the family inheritance. Later, Rebekah would deceive her own husband so that she and Jacob could swindle the family blessing. Jacob learned his lessons well, too, for a few chapters later he too played favorites, loving Rachel more than Leah.

Now baptize this family pathology with a dose of religion: "God blessed Isaac" (26:3, 12). Which is to say that He carried out His plans for human redemption through one of the twin boys but not the other. Jacob, not Esau, became the father of the nation Israel. Through four women — the sisters Rachel and Leah, and their slaves Bilhah and Zilpah — Jacob fathered twelve sons who became the heads of the twelve tribes of Israel. Esau became the titular head of rival Edom (Genesis 36). Fratricide would characterize their later family history.

|

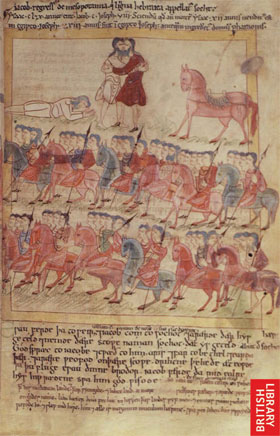

Meeting of Jacob and Esau, 11th century Old English Bible by Aelfric. |

There's mystery and an odd sort of encouragement in this Semitic family history that's so central to the story of salvation. We don't know why God chose Isaac instead of Ishmael, or one of Keturah's six boys, or Jacob instead of Esau. It's not clear why we learn so tantalizingly little about Keturah's six boys or Ishmael's twelve sons. No explanation is offered. His choice appears entirely random and arbitrary. In that all of these undeserving characters are so deeply flawed, so entirely human, God's choice was clearly not based upon merit.

None of the players in this story come off well. None appeared to offer better mettle for the history of salvation. Far from it, and therein we can take encouragement. These people and their families look, feel, sound and act like us. But God worked just as mightily through the statistical improbabilities and practical challenges of infertility, multiple births and deviant behavior. In His gracious hands the incidental, the accidental and the ordinary become the material of redemptive history, both in ancient Israel and in our own family stories today.

For further reflection

* Why do you think some Christians seem to suggest that our families should be perfect or free from problems?

* How has God worked in and through your own family's brokenness?

* Consider how the genealogy of Jesus affirms God's solidarity with fallen humanity. On page one of his gospel Matthew lists forty-two men in Jesus's genealogy, then four women with unsavory pasts. Tamar was widowed twice, then became a victim of incest when her father-in-law abused her as a prostitute (Genesis 38). Rahab was a foreigner and a whore who protected the Hebrew spies by lying. Ruth was a foreigner and a widow, while Bathsheba was the object of David's adulterous passion and murderous cover-up (Matthew 1:1–17). This is the family tree of Jesus our Lord.

Image credits: (1) J. Paul Getty Museum; (2) Fine Arts Museum, San Franciso; (3) Wikipedia.org; and (4) British Library Images Online.