From Ashes to Fire

First Sunday in Lent 2007

A guest essay by Nora Gallagher, the author of the newly released Changing Light: A Novel, and the best sellers Things Seen and Unseen and Practicing Resurrection. She is a member of Trinity Episcopal Church Santa Barbara and a layperson licensed to preach by the Bishop of Los Angeles. She was a postulate for holy orders in the Diocese of Los Angeles and decided to remain a member of the laity (see Practicing Resurrection).

For Sunday February 25, 2007

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year C)

Deuteronomy 26:1–11

Psalm 91:1–2, 9–16

Romans 10:8b–13

Luke 4:1–13

|

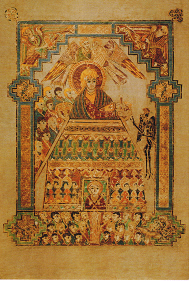

Temptation of Christ, Book of Kells illuminated MSS, c. 800. |

Today, the first Sunday in Lent, we join Jesus in the desert, where he spent forty days wrestling with “Satan’s” temptations. Our pilgrimage began on Ash Wednesday, when ashes were imposed on our foreheads. Lent is a journey in which each step we take matches one in the gospels. Victor Turner, the celebrated anthropologist, said that on a pilgrimage the whole of geography takes on symbolic meaning. Lent is like a slow dance, in which each movement reflects a movement elsewhere, each step is matched by another in the parallel, gospel, world.

The geography begins in the desert. In the crucible of heat and sand, Jesus was trying to figure out, as Frederick Buechner writes, “what it meant to be Jesus.” In the weeks that follow Luke will recount what Jesus did later. He walked from town to town, sat down at the table with a tax collector, healed a leper, ate grain on the Sabbath, used the wrong fork. It is not at all clear to me that he knew who he was as in: “I’m the Son of God.” Rather, it looks more like he discovered, step-by-step, more about himself as time wore on, as he walked, and waited, and healed.

At the end of Lent, on Palm Sunday, we will walk with Jesus into Jerusalem, the city where crowds welcomed him on the Sabbath by spreading palm branches under his feet, and where he was executed by the week’s end.

Lent is a journey towards the cross. And towards a tomb, and the mysterious, unending joy of those who found that tomb empty. Finally, on the eve of Easter, we will light the tall, white Paschal candle in a darkened church. A deacon will sing, “The light of Christ.” Lent is a journey, as a biblical scholar put it, from ashes to fire.

We are people of the word, and of the story. The essence of healing, perhaps the essence of what we mean by resurrection, is to take the chaos and trauma of our lives and rewrite them. When we find a compassionate listener, either in our own hearts or outside ourselves, in someone else, in therapy, in analysis, with a priest or a best friend, we have the chance to rework the material of our lives, to create a “fiction” if you will, meaning, not a false story, but a narrative with purpose and meaning. I ponder the resurrected Jesus, and I think about how out of death new life was written and revealed.

The promise of the Lenten journey, from Ash Wednesday’s ashes to Easter’s fire, is that we will find, by entering into the readings, our own unfolding stories. The goal is to bring their geographies into the self, to bend beneath them, to allow the soul to find its narrative within them.

|

Temptation of Jesus, Spain, c. 1125. |

Let’s take a look at today’s gospel: the temptations laid before Jesus in the desert. “Satan” put before him these three: if you are hungry, change stones into bread. If you are the son of God, leap from a tower and rely on angels to rescue you. If you bow down before me, all the kingdoms of the world will be yours.

These “temptations” once seemed too archaic for my modern mind, but as I’ve thought about them over the years, they have come to represent things all too familiar. Satan’s temptations represent magic, rescue, fame and power—they beckon me every day of my life. Just around the corner lies happiness, a new lover will provide lasting bliss, if I had what she has, then I would be. . .

These are the fantasies, the illusions, that suck out my vitality, that keep me from discovering my own rich reality. To come to terms with illusion is one of the great jobs of our lives: to discern what is fantasy and what is reality, what is dead and what is alive, what is a narcotic and what is food, what are stones and what is bread. It is dangerous, wrenching and unavoidable. In the desert, Jesus fought for his life.

What was asked of Jesus is what is asked of us, that we give up illusion, its false promises and its addicting inertia, and “come to our senses,” come to living bread.

And, if you think about it, Jesus will accomplish each one of these “temptations,” but by taking a different course. He will change stones into bread: a few loaves of bread and five fish will feed five thousand. He will "hurl himself from a tower" and be “caught by angels,” by giving up his life on the cross. He will be worshipped, by humbling himself as a servant.

If, instead of waiting for stones to be changed to bread, we share the food we have; if, rather than waiting for the fantasy job or lover, we engage the people and work of our lives; if, rather than waiting for rescue, we lay down our lives for our friends, then we depart the world of deadly illusion for a living reality in which “every day the real caress,” Anais Nin said, “replaces the ghostly lover.”

In my new novel, Changing Light, two of my characters talk about this Gospel. Eleanor is a painter, living in New Mexico, returning to church after a long absence. Leo is a physicist, AWOL from the atom bomb project, at the secret city of Los Alamos. She has found him lying by the river; she doesn’t know who he is but something compels her to look after him. He’s been in her house for awhile, and they have begun to talk. On Easter, Eleanor returns from church and checks on Leo:

Eleanor says: "Do you know the gospel story that is told at the beginning of Lent?”

“I am afraid not,” Leo replied.

Eleanor laughed. “Why would you know it?” Then she tells him about the gospel we have just heard.

“That’s only vaguely familiar,” Leo says.

“I was thinking about it today in church,” she said. “That the Resurrection, that Easter, actually, is like changing stones into bread. Only differently than how the devil had in mind. I mean, I think the devil wanted a kind of magic act. And Jesus wouldn’t do it. But if you think of Jesus rising from the dead, it’s like finding life again, after death. Or, I don’t know how exactly to say this, but painting is like that, sometimes. Sometimes you can work and work and work, and nothing goes well, and then suddenly, it happens. As if by itself. Stones turn to bread. But it takes an element of, I don’t know, seeing, I guess, and, then, grace.”

Leo smiled at her. “That is at once very foreign to me and yet very nice,” he said. “It’s certainly the first time anyone has said anything to me about the resurrection of Jesus that made any sense.”

Eleanor grinned. ”Oh Lawdy,” she said shyly.

Then Leo says: “That is what we were doing,” Leo said, almost to himself. “Or maybe the opposite.”

“What?”

“How does that story go on, I mean the one about Satan and Jesus?” Leo asks.

Eleanor replies: “Satan suggests that, if Jesus is the son of God, that he jump from a high tower and God’s angels will save him.”

“And?"

“Jesus declines the invitation.”

“What happens to Satan?”

“He departs,” she said, “The gospel says, ‘until another time.’”

“Always until another time,” Leo replied.

Leo was thinking about the atomic bomb, of the magic act of changing a collection of theories into a weapon, and he was pondering whether that was changing stones to bread or its opposite.

Illusion is not only a personal problem, it’s a collective temptation. We are asked, as citizens, also, to discern the difference between illusion and reality, stones and bread.

|

Temptation of Christ, Fra Angelico, c. 1450. |

I think of God as the ultimate compassionate listener. I can bring all of my chaos and trauma to her or to him, the ways I whine, complain and duck the truth. Lent is set aside to do just that: bring it all to consciousness. It’s not easy to face our own darkness, our own ashes. We are all going to come up short. I know I am. As a friend said, when she wanted to take a day off from work: I’m just going to call in ugly. We’re all going to have to call in ugly during Lent, that’s why we’re doing this together.

I once asked a friend of mine who is a therapist how to stop projecting onto others my own fears and weakness, that is, how to love, and she said: “You must enlarge your capacity to suffer.” The work of Lent is to rewrite the story by enlarging our capacity to take in the parts that we always want to leave out: the parts that aren’t so pretty, that make us less heroic but more real. If I had what she has, I would be? Her. Not me. If I was famous I would be: still me, only famous, with another whole set of problems. If I had a new lover then I would be? Blissful, for awhile, and then he, too, would probably neglect to pick up the towels in the bathroom. I make light of it, but we know how much we have to accept about ourselves, all the hard truths, that will cause us to enlarge our own humanity, and write a new, and I would say, a better, story.

In Lent, accepting the ashes will enlarge our capacity to suffer. And, of course, with that work will come an enlarged capacity for joy. That’s the fire.

For further reflection:

* During Lent, when I confess, I’ve been focusing on just one sin, one creepy thing I did or didn’t do, a thing done or left undone, rather than trying to bring everything bad to God, all at once. You might try it.

* How does having someone listen to us help us to rewrite our stories?

* What are your ashes? What is your fire?