For Sunday October 11, 2020

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year A)

Isaiah 25:1-9

Psalm 23

Philippians 4:1-9

Matthew 22:1-14

Sometimes, the most honest response to a story from Scripture is regret. Regret, repentance, and reorientation. This is especially true of Bible stories we inherit from other people — stories that someone else hands to us, wrapped in layers of interpretation so thick, we can’t tell where the interpretation ends and the story begins.

To put this another way, sometimes, we need to “unsee” a Biblical text before we can see it. New Testament scholar Amy-Jill Levine argues that if religion is supposed to “comfort the afflicted and afflict the comfortable,” then Jesus’s parables are meant to do the latter. If we read them and find ourselves unprovoked, then we aren’t really seeing them. Jesus was no teller of cozy bedtime stories; his parables are designed to show us things we don’t want to see.

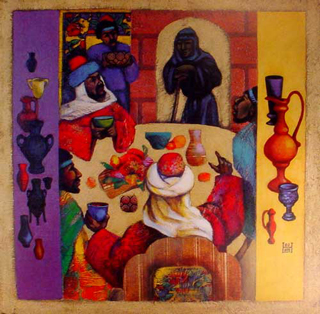

This week’s parable of a wedding banquet gone awry is no exception. No effort to soften its jagged edges will suffice; it is a harsh, hyperbolic story, steeped in violence. If someone were to make it into a movie, the genre would be horror.

And yet for centuries, we Christians have attempted to soften and sanitize this brutal story. Most often, we’ve done so by flattening the parable into allegory. In the rendering I inherited as a child, the king in the parable is God, the son/bridegroom is Jesus, the wedding feast is the Messianic banquet, the rejected and/or murdered slaves are the Old Testament prophets, and the A-list guests who refuse to attend the wedding are God’s “chosen people,” the Israelites. And the B-listers? Those last minute guests who come in off the streets to fill the banquet hall instead? Those folks are us. The gentiles.

There’s no question about it; this is a convenient interpretation. For us, I mean. No discomfort or affliction to speak of — just one heck of a party. What could be better? The snobs who renege on their RSVPs get their comeuppance — they die — but we who have the good sense to say “yes” to the king end up snug and cozy in his palace, feasting on wine and caviar while the world burns.

|

This is the interpretation I grew up with, and for a long time I saw no problems with it. In fact, the interpretation was so airtight, it prevented me from accessing the actual parable at all. I glossed right over the extremity of its violence and the cartoonish quality of its plot. I reveled in its implicit judgment of “those other people” who stupidly reject the king’s invitation, and automatically placed myself in the category of those who flock to the wedding feast — fancy garb at the ready.

I grieve this reading now, and I repent of it. I repent of the way it automatically privileges me — my obedience, my good choices, my reward. I repent of the callous acceptance of vindictiveness, violence, and cruelty at its heart. And I repent of the anti-Semitism it espouses in the name of Christ.

Think about it. Once again, in this traditional interpretation of the story, the Jewish people get everything wrong, lose their coveted place on God’s A list, and take a backseat to the more faithful and more deserving (gentile) church. What a dangerous and wounding angle on the story — an angle that participates in the long, bloody history of the church’s abusive relationship with the Jewish people from whom we come.

But there’s something else to repent of in the traditional reading of the story, namely, its false and terrifying depiction of God. As Christ’s followers, do we really believe in a God as petty, vengeful, hotheaded, and thin-skinned as the king in this parable? A God who burns an entire city to the ground in order to appease his wounded ego? A God who forces people to celebrate his son’s marriage while his armies wreak destruction right outside? A God who casts an impoverished guest into the “outer darkness” for reasons the guest absolutely can’t control?

Obviously, the answer is no. Of course we don’t believe in a God as monstrous as that. Do we?

I know that I’m pushing hard against tradition here, but the reading I inherited will not hold if we begin with a core commitment to the radical grace, mercy, hospitality, and sacrificial love of God. I mean, seriously? Invited guests who would rather commit murder than attend their sovereign’s royal wedding? (How unpopular and horrid a sovereign!) Partygoers who have no choice but to carry on eating, drinking, dancing, and celebrating while their city burns to the ground? A king who invites a homeless guy into his palace and then banishes him for lacking formalwear? Honestly, why do we try to make this version of the story OK when it isn’t OK?

I wonder now if Jesus tells the parable in such an extreme and offensive way precisely because we do believe in a God as harsh as the king who turns his armies loose on his own people — and we need the help of hyperbole in order to recognize it. Is it possible that Jesus is offering us a critical description of how God’s kingdom is often depicted by God’s own followers? What if the king in the parable isn’t God at all? What if the king is what we project onto God? What if the king embodies everything we’ve learned to associate with divine power and authority from watching other, all-too-human kings and rulers? Kings like Herod. Conquerors like the Roman Empire of Jesus’s day. Leaders in our own time and place who exercise their authority in abusive, violent ways, compelling their followers to gleefully celebrate in circumstances that call for lament.

|

Do we — consciously or not — present to the world a God who is easily offended, easily displeased, easily dishonored? A God whose holiness rests on the foundation of an unyielding and even violent anger? A God whose need to save face finally trumps his own graciousness and hospitality? A God whose invitation to salvation has strings attached to it?

It’s easy enough to say no, we don’t. Yet we are surrounded by people who have been victimized by brutal religion, many of them bludgeoned by the “Christian” depiction of a God who is angry, withholding, transactional, and perfectionistic. Some of us have friends or family members who have experienced the church as petty, ungenerous, and judgmental. Most of us know Christians so narrow-minded and exclusionary in their faith practice that we dare not approach them. Some of us still carry deep wounds from the years or decades we spent appeasing the “king” we mistook for God.

“The kingdom of heaven may be compared to a king who gave a wedding banquet for his son,” Jesus says by way of introduction to his parable. Okay, what will happen if we take him at his word? What might we learn if we attempt an honest comparison between God’s coming kingdom, and our current one? Are our tables open to all who come, and does our love extend to those who initially refuse our invitation? Are we willing to extend a welcome to those who show up unprepared, unwashed, unkempt? Do we take offense when people shy away from our banquet, or do we listen as they explain why our invitation strikes them as unappealing or frightening? Do we really want to open our arms wide, or do we have a secret stake in seeing some people end up in the “outer darkness”?

In the end, are we known for our impeccable honor, or for our scandalous hospitality?

I begin with repentance, and now turn to reorientation. That is, I turn to the possibility of seeing this parable with new eyes. Eyes starving for Good News — not the mingy Good News that secures my salvation and my comfort at the expense of other people's bodies and souls — but rather, the Good News of the Gospel that is inclusive, disruptive, radical, and earth-shattering. The Good News that centers on the Jesus I trust and love. What would it be like to look for Jesus and his Good News in this story?

Here’s one possibility: What if the “God” figure in the parable is the one guest who refuses to accept the terms of the tyrannical king? The one guest who decides not to “wear the robe” of forced celebration and coerced hilarity, the one guest whose silent resistance leaves the king himself “speechless,” and brings the whole sham feast to a thundering halt? The one brave guest who decides he’d rather be “bound hand and foot,” and cast into the outer darkness of Gethsemane, Calvary, the cross, and the grave, than accept the authority of a violent, loveless sovereign?

|

Yes, it's disturbing. But stay with it for a minute.

What would change for you if Jesus was the unrobed guest and not the furious king in this story? How would you have to change to welcome such a guest? To honor such a guest? To accompany such a guest? What robes of privilege, power, wealth, empire, location, and complicity would you have to refuse to wear? What holy rebuke would you have to speak or embody when the king demands your cheery presence at his table? What feasts would you have to forego to follow the unrobed dissenter when he's escorted into the darkness, bound and broken for the sake of love?

To read the parable this way is to accept its indictment. To sit under its searing, breaking grace, and confess that I need to change my location in a story I thought I knew inside out.

The parables of Jesus are meant to afflict the comfortable. The parables are meant to show us who God is, and who God isn't. So. May we embrace the loving God who is rather than the vindictive God who isn’t. May we choose affliction over apathy, even when it costs us a spot in the palace. May we refuse sham banquets while our cities burn and our streets run with blood. May we always reject the invitations of heartless kings. And may we, like Christ the unrobed guest, disarm all powers that bind God's children, and render the world's oppressors speechless in his name.

Debie Thomas: debie.thomas1@gmail.com

Image credits: (1) Pericope.org; (2) Orthodox Christian Network; and (3) Priestly Fraternity of St. Peter.