For Sunday March 25, 2018

Palm Sunday

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year B)

Lectionary Essay for Palm Sunday (Year B, for the March 25th, 2018 RCL)

Readings:

Mark 11:1-11 or John 12:12-16

Psalm 118:1-2, 19-29

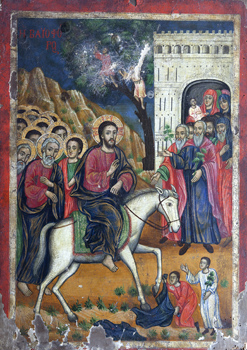

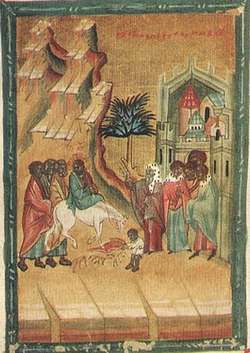

This week, we prepare for Palm Sunday, the last Sunday of Lent, and our gateway into the trials and triumphs of Holy Week. If your religious history is anything like mine, you know the drill. You’re adept at making neat little crosses out of palm fronds. You know how to walk in an orderly procession, carry a “Hosanna” banner, and shout, "Blessed is he who comes in the name of the Lord!”

When I was little, Palm Sunday had a cheery, birthday-party warmth to it. It was a celebration day — a day to gather in God’s house with other Christians, and give Jesus the adoration he deserves. I loved carrying palm branches up to the altar, singing upbeat songs along the way. Even as a kid, it pleased me to re-enact a day when Jesus enjoyed a heartfelt outpouring of praise from his followers

If someone had told me back then that the Triumphal Entry was actually a subversive act — much more a protest than a parade, a party, or an impromptu worship service — I would have recoiled. I was accustomed to a Jesus who desires worship. Not to a Jesus who calls for peaceful but risky engagement against real-world injustice.

But according to New Testament scholars Marcus Borg and John Dominic Crossan, the Triumphal Entry was just such an act of intentional protest. Jesus was not the passive recipient of impromptu adoration on Palm Sunday. Though worship might have happened along the way, it was not the point. Rather, Jesus' parade-by-donkey was a staged joke. It was an act of political theater, an anti-imperial demonstration designed to mock the obscene pomp and circumstance of Rome.

In their compelling book, The Last Week: What the Gospels Really Teach About Jesus' Last Days in Jerusalem, Borg and Crossan argue that two processions entered Jerusalem on that first Palm Sunday; Jesus' was not the only Triumphal Entry. Every year, the Roman governor of Judea would ride up to Jerusalem from his coastal residence in the west, specifically to be present in the city for Passover — the Jewish festival that swelled Jerusalem's population from its usual 50,000 to at least 200,000.

| |

The governor would come in all of his imperial majesty to remind the Jewish pilgrims that Rome was in charge. They could commemorate an ancient victory against Egypt if they wanted to, but real, present-day resistance (if anyone was daring to consider it) was futile; Rome was watching.

Here is Borg and Crossan's description of Pontius Pilate's imperial procession: "A visual panoply of imperial power: cavalry on horses, foot solders, leather armor, helmets, weapons, banners, golden eagles mounted on poles, sun glinting on metal and gold. Sounds: the marching of feet, the creaking of leather, the clinking of bridles, the beating of drums. The swirling of dust. The eyes of the silent onlookers, some curious, some awed, some resentful."

According to Roman imperial belief, the emperor was not simply the ruler of Rome; he was the Son of God. So for the empire's Jewish subjects, Pilate's procession was both a potent military threat and the embodiment of a rival theology. Armed heresy on horseback.

This is the background, Borg and Crossan argue, against which we need to frame the Triumphal Entry of Jesus. That Jesus planned a counter-procession is clear from St. Mark's account of the event. Jesus knew he was going to enter the city on the back of a donkey; he had already made arrangements to procure one. As Pilate clanged and crashed his imperial way into Jerusalem from the west, Jesus approached from the east, looking (by contrast) ragtag and absurd. His was the procession of the ridiculous, the powerless, and the explicitly vulnerable. As Borg and Crossan remark, "What we often call the triumphal entry was actually an anti-imperial, anti-triumphal one, a deliberate lampoon of the conquering emperor entering a city on horseback through gates opened in abject submission."

Elsewhere, Crossan notes that Jesus rode "the most unthreatening, most un-military mount imaginable: a female nursing donkey with her little colt trotting along beside her." In fact, Jesus was drawing on the rich, prophetic symbolism of the Jewish Bible in his choice of mount. The prophet Zechariah predicted the ride of a king "on a colt, the foal of a donkey." He would be the nonviolent king who'd "command peace to the nations."

|

For those of us living in the United States these days, it’s hard not to draw contemporary parallels. As I write these words, officials at the Pentagon — under orders from President Trump — are planning a multimillion dollar military parade, a symbolic show of force from the world’s most powerful nation. Concurrently, as thousands of children and teenagers around the country “walk out” of their schools to plead for commonsense gun control in the wake of yet another mass shooting, detractors are calling instead for more guns — more conceal-and-carry options, fewer restrictions on gun ownership, and more armed adults in schools. What, I wonder, would Jesus-on-a-colt have to say about our obsession with might? Where and how would his parade-of-the-radically-vulnerable speak truth to today’s centers of power?

I have no idea — and the Gospel writers don't tell us — whether anyone in the crowd on that first Palm Sunday understood what Jesus was doing. Did they get the joke? Did they catch the subversive nature of their king's donkey ride?

I suspect they did not. After all, they were not interested in theater; they were ripe for revolution. They wanted — and expected — something world-altering. An ending-to-the-story worthy of their worship, their fervor, and their dusty cloaks-on-the-road. But what they got instead was a parade of misfits. A comic donkey-ride. As New Testament scholar N.T Wright puts it, what they got was a mismatch between their outsized expectations and God's small answer.

Which raises an interesting question. What did Jesus accomplish on Palm Sunday? Did a Roman officer from the "real" procession trot over to check out the disturbance in the east? If so, what did he make of Jesus’s parade? Did he turn his stallion around fast to whisper something ominous into Pilate's ear?

I don't think it would be an exaggeration to say that Jesus' political joke hastened his crucifixion. He was no fool; he knew exactly what it would cost him to spit in Rome's face. Like all good comedians, he understood that real humor is in fact a serious business; at its best, it points unflinchingly to truths we'd rather not see.

For those of us who struggle to reconcile the role of God's will in the death of Jesus, this story offers a helpful but troubling clue: it was the will of God that Jesus declare the coming of God's kingdom. A kingdom of peace, a kingdom of justice, a kingdom of radical and universal freedom. A kingdom dramatically unlike the oppressive and violent empire Jesus challenged on Palm Sunday.

|

So why did Jesus die? He died because he unflinchingly fulfilled the will of God. He died because he exposed the ungracious sham at the heart of all human kingdoms, holding up a mirror that shocked his contemporaries at the deepest levels of their imaginations. Even when he knew that his vocation would cost him his life, he set his face "like flint" towards Jerusalem. Even when he knew who'd get the last laugh at Calvary, he mounted a donkey and took Rome for a ride.

During this Lenten season, a Franciscan blessing has marked the end of Sunday services at my church. It’s a beautiful but challenging prayer that invites me to move straight from Sunday worship to weeklong works of mercy and justice: "May God bless us with discomfort — discomfort at easy answers, half-truths, and superficial relationships, so that we may live deep within our hearts. May God bless us with anger — anger at injustice, oppression, and exploitation of people, so that we may work for justice, freedom, and peace. May God bless us with tears — tears to shed for those who suffer from pain, rejection, hunger, and war, so that we may reach out our hands to comfort them and turn their pain into joy. And may God bless us with foolishness — enough foolishness to believe that we can make a difference in this world, so that we can do what others claim cannot be done."

Two processions. Two kingdoms. Two symbolic journeys into Jerusalem. Stallion or donkey? Parade or protest? Which will I choose? Sometimes (I’ll be honest), I'd rather just wave a palm branch, sing a few rounds of "Hosanna,” and go home. The actual praise and worship Jesus invites me to enact on this last Sunday in Lent is far riskier; his donkey ride cost him everything. I dare not join Palm Sunday’s parade too casually.

Image credits: (1) A Reader's Guide to Orthodox Icons; (2) Wikipedia.org; and (3) Wikipedia.org.