From Our Archives

For earlier essays on this week’s RCL texts, see Michael Fitzpatrick, Learning the Lord’s Paths (2022); Debie Thomas, Afflicting the Comfortable (2019) and Go and Do Likewise (2016); and Dan Clendenin, The Parable of the Good Samaritan (2013) and Remembering Romero (2010).

This Week's Essay

By Amy Frykholm, who writes the lectionary essay every week for JWJ.

Deuteronomy 30:14: “The word is very near to you.”

For Sunday July 13, 2025

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year C)

Psalm 82 or Psalm 25:1–9

Colossians 1:1–14

Luke 10:25–37

It is tourist season where I live. We also call it “no left turn season” as it becomes impossible to enter the two-lane highway that bisects our town. Amidst the countless young families and groups of retirees are lonelier, dirtier figures who didn’t arrive in air-conditioned cars or RVs. They are immediately recognizable by a certain gauntness and the scrapes and bruises on their legs.

These are the through-hikers. Some are hiking from Denver to Durango on the Colorado Trail. Others are hiking from Mexico to Canada on the Continental Divide Trail. All of them have undertaken the vulnerable and difficult work of walking hundreds of miles through strange and precarious terrain.

One year we met Zeltzin Atketzalli, the first Mexican woman to complete the “triple crown” of through-hiking: the Pacific Crest Trail, the Appalachian Trail, and the Continental Divide Trail. Zeltzin introduced us to the concept of the “trail angel.” Trail angels are those people who appear to you on the trail when you are in need. They give you rides into town, let you do laundry at their houses, offer you a meal when your supplies have run low.

One day, she said, she’d been feeling at her lowest on the Pacific Crest Trail, full of loneliness, hunger, and self-doubt. Suddenly there appeared in front of her an impromptu taco stand. A trail angel, who will forever be anonymous to her, had decided to set up a taco stand in the woods and provide tacos to all through-hikers. He himself had been helped on the trail once, he said, and wanted to pay some spontaneous kindness forward.

|

|

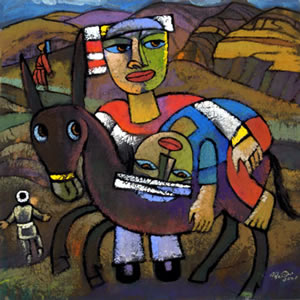

“The Good Samaritan” by He Qi (b.1951). He Qi is a contemporary artist whose work blends Chinese folk art and traditional painting with Western iconography and modern art.

|

Years earlier my husband and I were driving into town when we saw a young man pushing his heavily laden bicycle into woods that we knew were privately owned and not a legitimate camping spot. We pulled over and invited him to our house, offering a shower, laundry, and hot meal. The man hesitated, looked over his shoulder into those unknown woods, and finally agreed. His name was Alessandro. He was from Italy and had undertaken the adventure of bicycling from Denver to Palm Desert.

He had been warned by relatives, however, not to meet Americans. He’d made a plan that would allow him to complete this epic bicycling trip by meeting as few people as possible. The landscape was beautiful, but the people, he’d heard, were dangerous and not known for their hospitality. They all owned guns and had the right to shoot you. “Do you own a gun?” he asked, as we eased into dinner conversation. We said we didn’t, and he was astonished.

Some in our community might wish that Jeremy was also a through-hiker — about to vanish forever from our lives on some outbound trail. Instead, he is one of the roughest regulars at our community meal. He starts fights and steals money. He’s hidden drugs in the sanctuary. He threatens people, and even when he doesn’t say anything, people feel uncomfortable in his very presence. Over the ten years that Jeremy has been a part of our community, we’ve tried just about everything: calling the police, kicking him out, securing a protection order, arguing with him, ordering him around, making policies about him. We’ve also always fed him, but lately we’ve given up on any and all strategies except food and trying to make him feel welcome. (We also try to connect him with mental health care.) Recently, however, we’ve noticed a change. On Pentecost, Jeremy came to church just at the moment when we were being anointed with oil, like the tongue of flame on our heads. The pastor anointed Jeremy with oil as well. “You are a beloved child of God,” she said. He sat still in the pew and wept.

|

|

“The Good Samaritan” by Sadao Watanabe (1913-1996). Watanabe was a Japanese printmaker who made folk art style prints using biblical texts for inspiration.

|

A few weeks later, Jeremy and I were at the food pantry together. Almost whenever the church doors are open, Jeremy is there. He’d long since gotten his box of food, and now he was hanging around, something I would have thought menacing a few months ago. I sat on the front steps, casting an occasional eye toward him. Jeremy himself was watching the woman who’d come over from another community to offer support to drug-addicted members of our community. She had NarCan and sterile pouches for needle disposal. She had information on treatment and a sweet attitude that won over everyone she talked to.

After she’d been out in the sun for about an hour, Jeremy brought her a Gatorade. After another hour, he delivered her some food. Several minutes later, as the sun rose higher, he went to his alley stash and returned with a sun hat. This is what Jeremy did with his anointing: he acted like a neighbor. “Go and do likewise,” Jesus says. Or perhaps “pay it forward,” or even “here are some tacos.”

| |

|

“Coptic Icon of the Good Samaritan.”

|

What I’ve never particularly liked about the parable in Luke 10 is how clear it makes the categories of “helped” and “helper.” The word neighbor doesn’t do that. In fact, you’d be hard pressed to find a word more straightforward than neighbor. It simply means “near one.” In Hebrew, Greek, and Aramaic, as well as English, the word emphasizes proximity.

Once I visited a church that served meals in a community impoverished by the closing of a factory. The church people had many protocols by which they maintained a distance between themselves and the people who came to eat. The door to the kitchen remained closed, and featured a large PRIVATE—STAFF ONLY sign. Specifically designated volunteers pushed carts with preloaded, uniform plates of food. The line between people who ate and people who served was carefully demarcated and policed.

I know these were good people doing good in their community. They were enacting the principles of the Good Samaritan in the best way they knew how. Yet every time we draw a distinction between us (the good people who are serving those needy people) and them (the people who need serving), we are missing the point. We are more like the priest and the Levite — adding distance where proximity is commanded — than like the Samaritan, who collapses the distance and enters into the broken neighbor’s reality with all that he has.

Weekly Prayer

Naomi Shihab Nye (b.1952)

Before you know what kindness really is

you must lose things,

feel the future dissolve in a moment

like salt in a weakened broth.

What you held in your hand,

what you counted and carefully saved,

all this must go so you know

how desolate the landscape can be

between the regions of kindness.

How you ride and ride

thinking the bus will never stop,

the passengers eating maize and chicken

will stare out the window forever.Before you learn the tender gravity of kindness

you must travel where the Indian in a white poncho

lies dead by the side of the road.

You must see how this could be you,

how he too was someone

who journeyed through the night with plans

and the simple breath that kept him alive.Before you know kindness as the deepest thing inside,

you must know sorrow as the other deepest thing.

You must wake up with sorrow.

You must speak to it till your voice

catches the thread of all sorrows

and you see the size of the cloth.

Then it is only kindness that makes sense anymore,

only kindness that ties your shoes

and sends you out into the day to gaze at bread,

only kindness that raises its head

from the crowd of the world to say

It is I you have been looking for,

and then goes with you everywhere

like a shadow or a friend.Naomi Shihab Nye (b.1952) was born in St. Louis, Missouri. Her father was a Palestinian refugee and her mother an American of German and Swiss descent. Nye is the recipient of numerous honors and awards for her work. She lives in San Antonio, Texas. This poem comes from her collection Words Under the Words: Selected Poems (Eighth Mountain Press, 1994).

Amy Frykholm: amy@journeywithjesus.net

Image credits: (1) www.heqigallery.com; (2) www.vocationnetwork.org; and (3) Pravmir.com.