Remembering Romero:

Amos the Prophet vs. Amaziah the Priest

For Sunday July 11, 2010

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year C)

Amos 7:7–17 or Deuteronomy 30:9–14

Psalm 82 or Psalm 25:1–10

Colossians 1:1–14

Luke 10:25–37

This week's reading from Amos relates one of the most dramatic encounters in all of Scripture. If the dust-up occurred today, it would go viral on YouTube. The actors in the drama come right from central casting. The script should come with warning labels like "not recommended for children," or "side effects include severe political and spiritual discomfort."

Amos wrote 2,800 years ago, but his prophecy reads like a Twitter alert. He's a good example of how in the Bible "prophecy" is more about forth-telling the truth about the present than fore-telling events in the future. Amos lived under the renowned king Jeroboam II, who reigned forty-one years (786–746 BC) and forged a kingdom characterized by territorial expansion, aggressive militarism, and unprecedented economic prosperity.

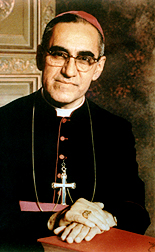

|

Archbishop Oscar Romero. |

Many people back then interpreted their fine times as evidence of God's special favor. Amos acknowledged that people were intensely and sincerely religious, but he saw things differently. Theirs was a privatized religion that ignored the poor, the widow, the alien and the orphan. It was a type of religion that degraded authentic faith to cultural ritual. Worst of all, Israel's religious leaders sanctioned the political and economic status quo that exploited the weak; these priests pimped religion for Jeroboam's empire.

Enter Amos. He preached from the pessimistic and unpatriotic fringe. He was blue collar rather than blue blooded. He admits that he was neither a prophet nor even the son of a prophet in the professional sense of the term. Rather, he was a shepherd, a farmer, and a tender of fig trees, a small town boy who grew up in Tekoa, about twelve miles southeast of Jerusalem and five miles south of Bethlehem. The cultured elites of his day despised Amos as a redneck. He was also an unwelcome outsider. Born in the southern kingdom of Judah, God called Amos to thunder a prophetic word to the northern kingdom of Israel.

That was a difficult divine call, but that's what this rustic prophet did. His fiery rhetoric opposed the powers of his day. With graphic details that make you wince, Amos describes how the rich crushed the poor. He singled out the affluent with their expensive lotions, elaborate music, and vacation homes with beds of inlaid ivory. He decried sexual debauchery where a man and his son abused the same woman, and lamented a corrupt legal system that sold justice to the highest bidder. He named predatory lenders who exploited vulnerable families, and religious leaders who aided and abetted all of this.

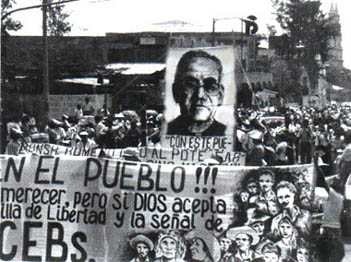

|

Assasination March 24, 1980 |

To the priests who defended, legitimized, and justified Jeroboam's corrupt reign, Amos delivered an uncompromising word of warning.

Amaziah the priest warned Jeroboam the king that Amos's preaching was unpatriotic and conspiratorial. He then tried to run him out of town. “Get out, you seer! Go back to the land of Judah. Earn your bread there and do your prophesying there” (7:12).

Then Amaziah said something that reveals just how completely he had identified religious faith with establishment power. It ought to send a chill up the spine of every religious leader who ever considered sucking up to power: "Don't prophesy anymore at Bethel, because this is the king's sanctuary and the temple of the kingdom" (7:13). With those words the religious justification of political empire is complete, and faith is reduced to patriotic cheer-leading.

Amos wouldn't be bullied; he had a word of his own for every priest who prostituted religion for empire: "Your wife will become a whore, your kids will be violently murdered, enemies will carve up the country, you will die far from home, and pagan Assyria will devour the political and economic empire you have tried to sanction in God's name" (7:17).

Despite the church's checkered history in relationship to power, privilege, and wealth, many saints have followed in the footsteps of Amos. This past spring many Christians commemorated the 30th anniversary of the martyrdom of Óscar Romero (1917–1980), the archbishop of San Salvador.

Romero was an unlikely martyr. He had studied in Rome, distanced himself from leftist radicals and their violence, and earned a reputation as a cautious conservative. The Salvadoran government was quite happy with his ordination as archbishop in 1977, whereas Marxist priests who ministered among the campesinos were dismayed. Then he did an about face.

|

Funeral March 30, 1980. |

A few weeks after his appointment as archbishop, Romero's close friend and Jesuit priest Rutilio Grande was slaughtered by machine-gun because of his ministry among the campesinos. The murder marked a decisive turning point. "When I looked at Rutilio lying there dead," said Romero, "I thought, 'If they have killed him for doing what he did, then I too have to walk the same path.'" Romero refused to meet with any government officials until they did an investigation. That never happened, and so in his three years as archbishop Romero never attended any state functions. The following week Romero canceled local services and held a single Mass in San Salvador to honor Grande; it was attended by 150 priests and 100,000 people.

For the next three years he spoke forcibly against the atrocities of the Salvadoran government and its para-military guerillas — the terror, torture, death squads, rape, and human rights abuses. Every week in his sermons, listened to on the radio by peasants all over the country, Romero detailed the horrors in an understated but explicit manner. He wrote a letter to President Jimmy Carter: "You say that you are Christian. If you are really Christian, please stop sending military aid to the military here, because they use it only to kill my people." Carter ignored the request.

Romero became the most outspoken critic of the government and a passionate defender of the dispossessed. His first death threat came from none other than president Arturo Molina, who warned him that priestly garments were not bulletproof. In his very last sermon, on Sunday March 23, Romero explained his Amos-like vocation: “I have no ambition of power, and because of that I freely tell those in power what is good and what is bad, and I do the same with any political group — it is my duty.”

|

20th-century martyrs in Westminster Abbey. |

His sermon continued: "I want to make a special appeal to soldiers, national guardsmen, and policemen: each of you is one of us. The peasants you kill are your own brothers and sisters. When you hear a man telling you to kill, remember God’s words, ‘thou shalt not kill.’ No soldier is obliged to obey a law contrary to the law of God. In the name of God, in the name of our tormented people, I beseech you, I implore you; in the name of God I command you to stop the repression!"

The next evening at about 6:30pm, a gunman shot Romero as he celebrated the Mass at a small chapel in the La Divina Providencia hospital where he lived. Later investigations established that the assassination was contracted by the government military.

One week later, 250,000 people attended Romero's funeral Mass. Thirty years later, on the anniversary of his death (March 24, 2010), Salvadoran president Mauricio Funes officially apologized on behalf of the government for Romero's assassination. A modern-day Amos, today Romero is honored as one of four 20th-century martyrs in Westminster Abbey, London.

For further reflection:

* On Óscar Romero see "Death Comes for the Archbishop," May 27, 2010, New York Review of Books, by Alma Guillermoprieto; the new documentary film Monseñor: The Last Journey of Óscar Romero, directed by Ana Carrigan and Juliet Weber; and "How We Killed Archbishop Romero," by Carlos Dada in the online newspaper El Faro.

* Psalm 82 for this week:

How long will you defend the unjust

and show partiality to the wicked?

Defend the cause of the weak and the fatherless;

maintain the rights of the poor and oppressed.

Rescue the weak and needy;

deliver them from the hand of the wicked.

Image credits: (1) Wikipedia.org; (2) Wikipedia.org; (3) MaryPages.com; and (4) Wikipedia.org.