From Our Archives

Debie Thomas, "The Voice of One Crying" (2019); Arthur J. Ammann, "Slogans vs Principles" (2016); Ron Hansen, "The Peaceable Kingdom" (2013).

For Sunday December 4, 2022

Second Sunday of Advent

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year A)

Isaiah 11:1-10

Romans 15:4-13

Matthew 3:1-12

Psalm 72:1-7, 18-19

This Week's Essay

Michael Fitzpatrick is a parishioner at St. Mark's Episcopal Church in Palo Alto, CA. After growing up in the rural northwest, he served over five years in the U. S. Army as a Chaplain's Assistant, including two deployments to Iraq. After completing his military service, Michael has done graduate work in literature and philosophy. He is now finishing his PhD at Stanford University.

During Advent, we celebrate the Incarnation, the story of the God who became flesh for our sakes. Over the past few years, many friends have shared with me their honest confusion about the Incarnation. What does it mean to say that God became flesh, that God walked about as one of us? Why does it matter? In the struggle of daily life, we aren’t typically wondering how God can be fully human; rather, we wonder how we can be fully human!

What if, contrary to our expectations, helping us become truly human is exactly what the Incarnation is about? I encountered Jesus in a culture of bullying, exclusion, and abuse. Christ delivered me from those who communicated, through words and actions, that I was somehow inferior. I needed a Lord of Lords who proclaimed, to me and my community, that God was not among my persecutors.

How does Jesus accomplish this? Not, I want to suggest, because Jesus is God is some flatfooted sense. If it takes being Almighty God to save me, what do I need God “in the flesh” for? Let God on High do the saving!

|

|

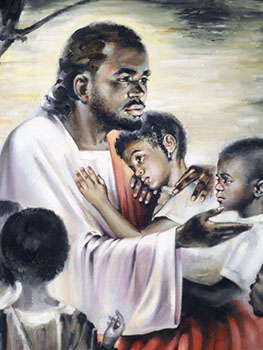

The Black Jesus Blesses the Children painting by Joe Cauchi, featured in Popular Mechanics Dec 2002.

|

Furthermore, simply asserting that “Jesus is God” can give the impression that Jesus isn’t God in the flesh. If someone says, “George Eliot is Mary Ann Evans,” many of us will hear this as saying that the author George Eliot, who appears to be a man, is really a woman, Mary Ann Evans. Likewise, many hear “Jesus is God” as saying that Jesus of Nazareth, who appeared to be a Jewish peasant, was really the infinite Creator. In other words, he wasn’t really one of us.

This way of talking about the Incarnation is not uncommon within Christian liturgical life. For instance, one of my absolute favorite hymns, “Let all mortal flesh keep silence,” gives the impression that Jesus was merely God wearing a human suit when, in the second verse, we sing these words: “King of kings, yet born of Mary, as of old on earth he stood, Lord of lords in human vesture. . . .” Acknowledging all their lyrical beauty, the words imply that Christ is really “Lord of lords” as of old and only apparently a mortal human walking the earth, as if God assumes and removes human nature the way we change our clothes.

Isn’t Jesus supposed to be both fully God and fully human?

Starting instead from Jesus’ humanity, the prophets anticipated a messiah born entirely within the story of the Jewish people. Isaiah 11 tells us of a shoot that will spring out of “the stump of Jesse,” a messiah who is fully a product of the historical ancestry of the Jewish people. “The spirit of the Lord shall rest on him,” yet he will remain as human as any one of us. It is here that the hope of the Incarnation makes its astonishing appearance. Jesus becomes savior not by being unlike us — infinite deity pretending to walk the earth — but by being completely one of us, assuming our total humanity in a particular human life for God’s liberating purpose.

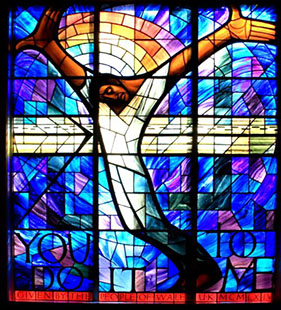

In a justly famous remark, Dietrich Bonhoeffer wrote from prison that only a suffering God can save. The suffering God comes forth in the particularity of the historical Christ. Jesus was a Jew, dwelling in occupied Palestine. Fully embedded in the Jewish story, he could be and was God’s fulfillment of the divine covenant with the Jewish people. In going to the Cross, Jesus suffered with and for his people, willingly being identified with the suffering poor and the criminal and the colonized. Jesus’ particular identification with the Jewish people, being of their stock and history, manifests his universal identification with all rejected peoples, of every subjugated stock and suppressed history.

|

|

Our Lady of Częstochowa, the "Black Madonna," a venerated icon of the Blessed Virgin Mary housed at the Jasna Góra Monastery in Częstochowa, Poland.

|

Jesus’ identification with the suffering Jewish people allows theologian James Cone to say that “Jesus is black,” not as a statement of historical specificity (Jesus was thoroughly Jewish), but as a claim about Jesus’ ongoing saving work for all people across time and space. “Jesus is black because he was a Jew,” Cone writes in his book God of the Oppressed. By manifesting God’s saving action in a particular historical Jewish life, Jesus identified himself with every individual human life that suffers, not for commiseration but to deliver them from their oppression. Wherever humans are afflicted and abused, they can say to themselves, Jesus was God assuming our suffering flesh. Wherever black folk are kept in chains, kept separate but equal, kept in the projects or in prison, there Jesus has assumed black flesh as part of God’s saving work to transform “oppressed slaves into liberated servants” (Cone).

One of the biggest impediments to living a complete human life comes from a society that implies, in words and deed and policies, that some of us are acceptable and the rest of us are not. This can be communicated in a religious key: God loves some, and rejects the rest. With all my deficiencies, why would God want someone like me? Doesn’t providence favor the rich, the powerful, the strong?

To all who have been told by human voices that God doesn’t accept you, the Incarnation is God’s assurance that, actually, God is entirely and utterly for you. In contrast to the lyrics above, the Rev. Carl P. Daw’s hymn “Gracious Spirit, give your servants,” set to the tune of Abbot’s Leigh, begins its second verse by singing, “Word made flesh, who gave up glory to become our great high priest, taking on our human nature to redeem the last and least…” The least among us are the ones whose flesh Christ assumed, for only by assuming the flesh of the last and least can we be assured that God was in Christ reconciling all people to himself, including us.

To experience salvation, we need a suffering God, one who suffers not only for all but in the flesh of all. Jesus did not come as a generic human. He came as a particular human. It matters what kind of human he came as. We can’t proclaim the good news of Jesus if he comes as the Caesar of the Roman empire, or a member of the oligarchs in Russia. We can’t tell his story if he comes as Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives or President of the United States. There’s no good news if Jesus is a tenured professor, the CEO of Twitter, or a charismatic leader of the Zealot activists.

The Gospel is only good news because Jesus comes as a slave, a powerless peasant in occupied Judea. It’s because he comes in this particular human life that an untouchable in India, a Syrian refugee, a young teenager with Tourette’s, and a black woman living under apartheid can each know that regardless of what the powerful in their society decree, the Creator has unconditionally acted to liberate them. Far from being ashamed of their bodies, God took their bodies, their flesh, their very skin and infirmities as his own. Wherever human flesh is declared repugnant to God, that is the flesh in which the Word comes.

|

|

The "Welsh Window" at 16th St Baptist Church in Birmingham, AL. Stained glass depiction of the crucified Black Christ created and donated by John Petts in response to the 1963 KKK bombing at the church.

|

When I wonder whether my Creator would accept my bullied, soiled flesh, my incorrect grammar, my humble upbringing, my lack of status or accomplishments or moral perfection, I am really asking, “If only that flesh assumed is saved, then did Jesus assume my flesh?” Could it have been my body that gestated in the Virgin Mary’s womb and was splayed on that old rugged Cross? Only if Jesus’ embodiment of God includes my flesh can I find saving hope. Thankfully I am assured that Christ died for me because Christ took particular Jewish flesh. That Jesus was a branch from the root of Jesse testifies that Jesus is the black Christ, the female Christ, the sexually trafficked Christ, the bullied Christ, the unemployed Christ, the bulimic Christ, the Alzheimer's Christ, and every other flesh that suffers. Because in Jesus God suffers, we can share Isaiah’s confidence that this messiah will be “an advocate for the poor” and “decide with equity for the meek of the earth.” For he came in their very flesh. What would you add to that list?

When we ignite the Advent candles, and eventually the Christ candle, we’re reminding ourselves that Jesus is “Light from Light,” the very essence and life of God brought forth in a genuine, completely human life for our sakes. The foregoing reflections have not merely been about the humanity of Jesus. In identifying with “the meek of the earth,” the humanity of Jesus bodies forth the divine love. God is the kind of God that suffers with the poor rather than protecting the rich. Jesus “lives God” by being, in his very flesh, God for us. When we see our flesh vindicated in Jesus suffering for us, we glimpse the divine Light that is the hope of all creation.

Advent testifies that the Incarnation makes possible our genuine humanity, by assuring us that God redeems our struggling lives even when our world rejects us. In the life of Jesus, God identifies with and redeems all flesh, no matter how scorned and outcast. It is this Jesus who as Light from Light “stands as a signal to the peoples . . . and his dwelling shall be glorious,” for it is the home where all flesh is part of Christ's very body.

A Prayer

Ephrem (4th century)

From God Christ's Deity Came Forth

From God Christ's deity came forth,

his manhood from humanity;

his priesthood from Melchizedek,

his royalty from David's tree:

praised be his Oneness.He joined with guests at wedding feast,

yet in the wilderness did fast;

he taught within the temple's gates;

his people saw him die at last:

praised be his teaching.The dissolute he did not scorn,

nor turn from those who were in sin;

he for the righteous did rejoice

but bade the fallen to come in:

praised be his mercy.He did not disregard the sick;

to simple ones his word was given;

and he descended to the earth

and, his work done, went up to heaven:

praised be his coming.Who then, my Lord, compares to you?

The Watcher slept, the Great was small,

the Pure baptized, the Life who died,

the King abased to honor all:

praised be your glory.

By Ephrem of Edessa, translated by John Howard Rhys, adapted and altered by F Bland Tucker, (Episcopal) Hymnbook 1982. From St. Ephraim the Syrian, Hymns on the Faith.

Michael Fitzpatrick cherishes comments and questions via m.c.fitzpatrick@outlook.com

Image credits: (1) Pinimg.com; (2) Angelus Catholic News; and (3) Artistry in Glass, Tucson, Arizona USA.