For Sunday August 15, 2021

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year B)

1 Kings 2:10-12, 3:3-14

Psalm 111

Ephesians 5:15-20

John 6:51-58

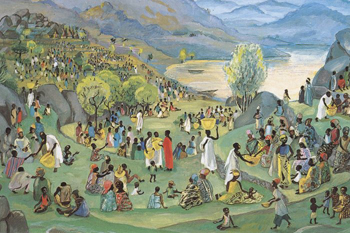

We’re still talking about bread. Which means we’re still talking about a God who longs to nourish us. For the past three weeks, I’ve written about what’s at stake for us in Jesus’s requirement that we “eat his flesh.” I’ve written about the significance of gathering around God’s abundant table. I’ve explored the deep hungers only God can satisfy. And I’ve considered what it means to carry divine bread on life’s precarious journeys.

This week, I’m thinking about Jesus’s invitation from the opposite side. That is, what is at stake for God in this invitation? If Jesus is the bread of life, what is it like for him to feed us? How does a feeding, nourishing God experience our “consumption?” What does Jesus feel when we refuse his sustenance?

Obviously, we can’t know for sure; our experience is not God’s. But I believe we can imagine, based on the witness of Scripture, and on the analogies and metaphors we find in our own lives.

For me personally, the analogy that comes closest is motherhood. My two children are young adults now, but over the past twenty-plus years, I’ve had a lot of time to reflect on my role as a feeder, nourisher, and sustainer of two human beings whose lives are intricately connected to my own. I’ve learned about the joys, the surprises, the fears, the frustrations, and the sorrows that come with becoming One Who Feeds, and I can’t help but wonder if my experiences mirror something of God’s.

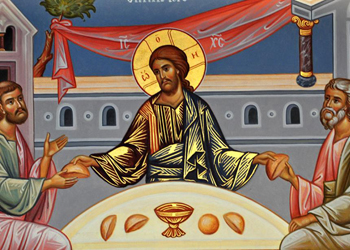

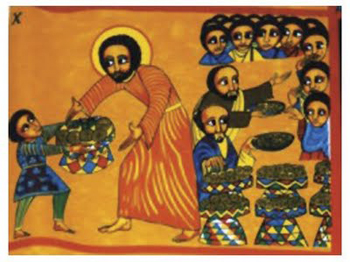

After all, both the Bible and Christian history are full of maternal images for God. In the book of Isaiah, God describes herself in childbirth: “I will cry out like a woman in labor, I will gasp and pant.” And again: “Can a woman forget her nursing child, or show no compassion for the child of her womb? Even these may forget, yet I will not forget you.” The Psalmist writes, “Out of my womb before the morning star I bore you.” In the Gospels, Jesus weeps over Jerusalem, describing himself as a mother hen who longs to gather her unwilling chicks under her wings. St. Augustine asks, “When all is well with me, what am I but an infant suckling your milk and feeding on you?” Ephrem of Syria writes, “He has given suck — life to the universe.” Teresa of Avila exclaims, “Oh Life of my life! Sustenance that sustains me! For from those divine breasts where it seems God is always sustaining the soul there flows streams of milk bringing comfort to all the people….”

|

So we have the witness of Scripture and tradition. But what does it mean? What can we learn about God’s heart, God’s character, God’s desire, by contemplating motherhood? I want to share two possibilities, each grounded in my own life experience. Two stories, then. One marked by surprise and wonder. The other, steeped in shadow.

Growing up, I didn’t see many women nursing their babies. So when my daughter was born, I knew that I wanted to breastfeed her — but that was all I knew. I had no idea how to begin. I didn’t have a clue as to what the commitment would entail in terms of time, skill, sleeplessness, or pain. It didn’t cross my mind that my newborn would be as clumsy and self-defeating as I initially was, having no idea how to latch on, how to suck efficiently, how to keep her own flailing fists out of the way, how to keep from choking when the milk let down.

In other words, our initiation into nursing was rough. The “natural” business of mother-feeding-child didn’t come naturally; it took practice, patience, tears (my daughter’s and mine) and help. For the first several weeks, I had a lactation consultant on call 24/7. During some feeding sessions, it took her, my husband, and my mom all holding, positioning, coaxing, and comforting my baby simultaneously to get the job done. I thought about giving up several times.

But then? Then we learned. We bonded. We developed a rhythm. We nested into each other, my daughter eagerly drawing the essentials of nutrition, warmth, affection, and protection from my body, and I in turn — aching with tenderness, urgency, full breasts and wild love — sharing my whole self with the little person cocooned in my arms.

|

Between my two children, I spent about four years of my life breastfeeding. In that time, I discovered the joy and wonder that comes with feeding so intimately. I realized with a kind of sacred bewilderment that I could sustain a human life with my own body. I glowed with pride and satisfaction when my babies’ cheeks filled out, and their limbs grew strong, and their eyes sparkled, and their bellies swelled with my milk. In the early weeks, when they had to nurse around the clock, I dreaded being away from them, even for an hour. I worried about something terrible happening to me before they were weaned. My body grew so attuned to their needs that my milk let down at the first hint of their cries. I learned what it is to give myself away, to delight in a fullness other than my own, to be nourished by the act of nourishing. To become food.

Again, the analogy isn’t perfect. But I wonder if Jesus’s desire to feed us, to be our bread, to give us his own flesh as perfect nourishment, is anything like the desire that overwhelmed me as a young mother when I held my infants in my arms. I wonder if he is patient when we fumble, and thrilled when we "latch on." I wonder if he worries over our hunger and delights in our fullness. I wonder if he takes pride in our growth and maturing. I wonder if he experiences pure joy each time we lean in and eat what he offers us.

“Those who eat my flesh and drink my blood abide in me, and I in them,” he says in our Gospel reading this week. I wonder what profound pleasure God takes in this intimate, bodily abiding.

A second story. A harder one. When my daughter was twelve years old, she slowly stopped eating. The descent was gradual: first, no desserts or sweets. Then, no carbs. Then, no between-meal snacks. Then, no meat. Eventually, no meals at all. Just pitiful little bites, scattered and useless. A single grape. One carrot stick. A tablespoon of plain yogurt or iceberg lettuce. Barely enough to sustain life.

Wrecked by anxiety, perfectionism, and American culture’s toxic obsession with thinness, our daughter had developed anorexia nervosa, one of the deadliest of all mental illnesses. Within a matter of months, our family dining table became a battlefield. Grocery shopping became an exercise in desperation and agony. All attempts at persuasion failed, and my husband and I faced the real prospect that our child might starve herself to death in the name of what her illness insisted was “health.”

There are no words to express what I felt as a mother as I watched my child waste away. All I wanted in the universe was to feed her. To cook anything she’d eat, to place warm and nourishing plates of food in front of her and coax her — even if it took hours — to take those essential nutrients into her weakened body. When she kept refusing, my heart broke, hardened, and broke again. Too many times to count. I panicked. I seethed. I grieved. I begged. I experienced a kind of powerlessness I hope never to experience again. I was her mother. The one who was supposed to nurture, nourish, feed, protect, and sustain my children. What was this monstrous sickness that made basic, elemental feeding impossible?

|

All these years later, my daughter is no longer as sick as she once was. She’s so much better. But eating disorders cast long shadows, and she still struggles to eat enough. She might struggle all her life. Which means I might, too. Bearing witness. Trying to help. Hoping. Fearing. Praying.

In our lectionary this week, Jesus doesn’t mince words: Unless you eat the flesh of the Son of Man and drink his blood,” he says, “you have no life in you.” I know that his words sound harsh and unforgiving, but I wonder if we might hear them as the desperate words of a parent who knows exactly what makes for life and what makes for death — and longs to spare his children the latter. I wonder if Jesus sounds the alarm so urgently because he knows how much and how badly we need the nourishing, life-sustaining food he alone can provide. I wonder if he, too, grieves and weeps, seethes and pleads, fears and hopes, when we walk away from his table, refuse his bread, and say no to his outstretched hands. I wonder how he sits with his own vulnerability, his own powerlessness — the terrible cost of the freedom he’s given us to starve ourselves if we so choose. I wonder how our Mother God yearns to gather us around her table, coax the bread of life into our mouths, and watch us once again thrive and flourish under her care.

“Whoever eats me will live because of me,” Jesus says. He is our bread, he is our bread, he is our bread. Our lectionary asks us to linger over this truth for a reason; this teaching is elemental. It is rock bottom. It is the core of who God is, and who we are. May we ever eat, and live.

Debie Thomas: debie.thomas1@gmail.com

Image credits: (1) Canadian Mennonite Magazine; (2) St. George's Episcopal Church, Fredericksburg, Virginia USA; and (3) Digital Collections of the Vanderbilt University Library.