She Gave All That She Had:

Finding Wisdom in the Lives of Three Widows

For Sunday November 8, 2009

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year B)

Ruth 3:1–5; 4:13–17 or 1 Kings 17:8–16

Psalm 127 or Psalm 146

Hebrews 9:24–28

Mark 12:38–44

The psalmist for this week offers some counter-intuitive advice: "Do not put your trust in princes, in mortal men, who cannot save. When their spirit departs, they return to the ground; on that very day their plans come to nothing" (Psalm 146:3–4). Despite our culture's propagandistic promises to the contrary, wealth and political power cannot save. In fact, there's exactly one place in Scripture where God laughs—when he scoffs at the pretensions of the powerful (Psalm 2:4).

"The Maker of heaven and earth," says Psalm 146, demonstrates his saving power in more subtle and less obvious ways. He's biased on behalf of the oppressed. He feeds the hungry, frees prisoners, and heals the blind. He lifts up those who are weighted down, he defends foreigners, protects the orphan, and sustains the widow. In this week's readings, three widows in particular play conspicuous roles in the coming of God's kingdom here on earth.

|

Naomi and Ruth. |

The story of Ruth occurs during the time of the judges, perhaps the darkest period in Israel's history. Famine ravaged the land. Anarchy reigned, and “every person did what was right in his own eyes.” Whereas idolatry was common, "the word of the Lord was rare” (1 Samuel 3:1). On the moral level, it was a time of debauchery; Judges 19, for example, records the murder of a nameless woman who was gang raped all night and then dismembered, a crime so heinous that it provoked a civil war within Israel.

In fact, Ruth is a story of three widows — the Israelite Naomi who fled Israel to Moab to escape famine, and her two foreign daughters-in-law, Orpah and Ruth. After ten years in Moab, and despite Naomi's protests, Ruth returned with her back to Israel. In Bethlehem, Ruth was the foreigner from an enemy country. She was childless. She was widowed from a mixed marriage. But she vowed to cling to Naomi, her Hebrew people, and to their God. Ruth secured an economic livelihood for her mother-in-law by gleaning fields among the hired hands. She followed Naomi's plan to ingratiate herself to Boaz, the owner of the fields she gleaned. All Bethlehem knew this foreign widow as a “woman of excellence” (Ruth 3:11).

Boaz was both a wealthy man and a near relative to Naomi's deceased husband Elimelech. As such, he not only had the means but also the obligation to “redeem” Ruth (and, in the process, Naomi). Another relative was even closer to Naomi than Boaz, but when he refused to redeem Ruth he cleared the way for Boaz. This second mixed marriage conceived a son, Obed, the grandfather of King David. Ruth's improbable story culminates when we meet her again on the very first page of the New Testament as a forebear of Christ Himself (Matthew 1:5).

Like Ruth, we encounter the widow of Zarephath at a pivotal juncture in Israel's history, and then meet her again in the New Testament. In The Kings and Their Gods (2008), Daniel Berrigan interprets 1–2 Kings as self-serving imperial records that portray Israel's kings as they saw themselves and wanted others to see them — God favors my regime and hates my enemies. He blesses us with their booty. No war crime is too heinous as a means to the delusional ends of these kings, and so on page after page political hell descends to earth.

|

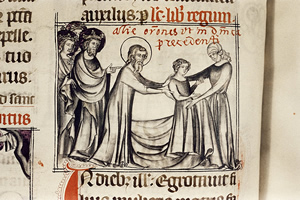

Elijah and the widow of Zarephath (Paris, 14th century). |

There is one political end in the book of kings, says Berrigan: extra imperium nulla salus, "outside the empire there is no salvation." The kings employ many pathological means to this end: untrammeled imperial ego, political retaliation with absolute impunity, military might, revisionist history, manipulation of memory and time, grandiose building projects, economic exploitation, virulent nationalism, and, sanctioning it all with divine approval, legitimation by religious sycophants.

A few dissenting voices objected to imperial power, but they were silenced as unpatriotic and seditious. The prophet Elijah was one such exception. Elijah was a lonely prophet, alternately manic and reclusive, who faced down the political powers of his day. He arrives on the scene in 1 Kings 17 "as though, after an endless night, the longing of the saints summoned a dawn light" (93). His story begins with a foreign widow from Zarephath in Sidon who at great personal sacrifice cares for him during a severe drought, and who in turn is cared for by Elijah.

This narrative of a nameless, alien widow and a Hebrew prophet offering each other mutual care across nationalistic boundaries assumed such central importance in Israel's sacred story-telling that Jesus repeated it a thousand years later. The impact was the same — the listeners were outraged at the role reversals. "I assure you that there were many widows in Israel in Elijah's time," said Jesus, "when the sky was shut for three and a half years and there was a severe famine throughout the land. Yet Elijah was not sent to any of them, but to a widow in Zarephath in the region of [enemy] Sidon. . . All the people in the synagogue were furious when they heard this" (Luke 4:25–28).

The third widow also epitomizes the reversals and subversions of power in God's kingdom. Women in general played a prominent role in the ministry of Jesus. Luke says that "many women" traveled with Jesus and supported him from their private means (Luke 8:1–3). Widows in particular occupy a major role in this story; the Greek word for "widow" (chera) occurs about twenty-five times in the New Testament.

That God cares for widows, and that his people should too, are prominent themes throughout the Bible. In this third story, though, it is the nameless widow who exemplifies the extravagant benefactor instead of the vulnerable beneficiary. At the temple Jesus observed "many rich people" making large donations. In stark contrast, a poor widow's gift amounted to "only a fraction of a penny." But whereas the rich give out of the convenience of their surplus, said Jesus, "this poor widow has given more than all the others. They all gave out of their wealth; but she, out of her poverty, put in everything — all she had to live on" (Mark 12:38–44). In the parlance of poker, this woman was "all in" when it came to following Jesus.

|

The Widow's Mite by W. T. Blandford-Fletcher. |

Many of the earliest Christians came from the lower socio-economic classes of Rome. The harsh critic Celsus (fl.175), for example, combined socioeconomic snobbery with intellectual elitism: "In some private homes we find people who work with wool and rags, and cobblers, that is, the least cultured and most ignorant kind. Before the head of the household they dare not utter a word. But as soon as they can take the children aside or some women who are as ignorant as they are, they speak wonders...If you really wish to know the truth, leave your teachers and your father, and go with the women and the children to the women's quarters, or to the cobbler's shop, or to the tannery, and there you will learn the perfect life. It is thus that these Christians find those who will believe them."

We normally don't turn to widows for wisdom. But what Celsus considered a criticism was for Paul an insight about living in the kingdom of God: "God chose the foolish things of the world to shame the wise; God chose the weak things of the world to shame the strong. He chose the lowly things of this world and the despised things — things that are not — to nullify the things that are, so that no one may boast before him" (1 Cor. 1:27–29).

Image credits: (1) Galus Australis; Jewish Life in the Antipodes; (2) Flickr.com; and (3) Worcester City Museums.