|

Meditation on Mortality

First Sunday in Lent 2009

For Sunday March 1, 2009

Lectionary

Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year B)

Genesis 9:8–17

Psalm 25:1–10

1 Peter 3:18–22

Mark 1:9–15

|

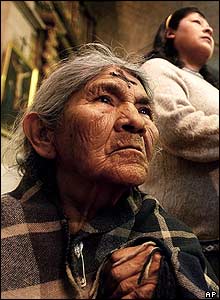

Receiving ashes in Papua New Guinea. |

Beginning this Ash Wednesday, Christians around the world begin their observance of Lent. Since the fourth century, Christians have observed the 40 week days before Easter as a season of reflection, repentance, fasting, abstinence, and acts of mercy. Perhaps you'll see a friend this week with ashes conspicuously smeared in the middle of her forehead. Maybe your colleague has mentioned giving up chocolate or alcohol.

In a culture that encourages indulgence, hubris and bravado, Wednesday's ashes signify an outrageously counter cultural act of humility. As a time when we befriend our brokenness, acknowledge that not all is well with our souls, and lament the pain of so many people in our world, Lent appeals to me as one of the most sensible and brutally realistic liturgical seasons of the year.

Ash Wednesday gets its name from the liturgical rite of dabbing ashes on the forehead of worshipers.The ashes remind us of our mortality. In words that are often read at Lent, God spoke to Adam in Genesis 3:19, “for dust you are, and to dust you will return.” In the Bible ashes are also a symbol of mourning (2 Samuel 13:19, Jeremiah 6:26), a stark metaphor that even Jesus invokes (Matthew 11:21). Ashes also signify an inner attitude of repentance, humility, self-denial, and abstinence.

On this point science and Christianity agree. In his book Beyond Science: The Wider Human Context, my favorite writer on Christianity and science, the Cambridge University particle physicist and Anglican priest John Polkinghorne, concludes: "It is as sure as can be that humanity, and all forms of carbon-based life, will prove a transient episode in the history of the cosmos." From star dust we came and to star dust we shall return.

Lenten humility is not an end in itself, some act of morbid self-hatred or misanthropic self-denial. And unlike the nihilist implications of the scientific outlook (cf. Julian Barnes, Nothing to Be Frightened Of), Lent anticipates and culminates in the Easter celebration of resurrection life. Whatever else Christians believe, we believe that God in Christ will vanquish sin and death, and so we're the ultimate optimists who affirm life. But until then, Lent reminds us that Easter's celebration of life must pass through the narrow and bitter way of death. This is true in a figurative sense; but it's also true in a literal sense. Jesus rose from the dead, but not before he died a real death; our hope is for the same. That's why at this time of year Christians find it entirely healthy and human to "remember death"—memento morum.

|

Ash Wednesday in Australia. |

Whereas Christians anticipate and reflect upon death, society tends to deny it. We idolize strength, vigor, and youth, and marginalize the weak, the elderly and the infirm. Age spots, decreased energy, wrinkles, aches and pains are anxious cause for diets, cosmetic surgery, and pill-popping, but almost never for a reality check. When death does come, as it surely will, morticians make our corpses appear as life-like as possible, and mourners insist how "beautiful and peaceful" the dead body looks.

Our denial of death finds deep roots in the Hebrew Scriptures. Consider the most pernicious lie ever told, when the serpent told Eve, "Surely you will not die" (Genesis 3:4). This lie, so mysterious back then and so irresistible today, harms us, for while it's normal and natural to avoid the unpleasant, to persist in loving this lie perpetuates the ultimate death wish.

In 1974 the cultural anthropologist Ernest Becker won the Pulitzer Prize for his book The Denial of Death. The fear of our eventual extinction is so terrifying, so anxiety-producing, Becker argued, that virtually all cultures construct elaborate schemes to deny our mortality and enable us to believe that we are immortal. In fact, Becker believed that perpetuating this denial of death constitutes one of the chief functions of culture. But denying death is disastrous. It causes us to form illusory, false selves, and even worse, thought Becker, on the social level it foments all the horrific violence and aggression against others that we see in our world today (since we must prove other death-denials as false, and even eradicate them, else ours is exposed as a lie).

If you are lucky, long before death reality will hit hard. Life will slap you around, and the older you get the harder it becomes to believe the serpentine denial of death. Friends die. Kids grow older and leave. Your longtime neighbors move. The newspaper obituaries suddenly provoke reflective reading rather than idle curiosity. Your physical capacities of both body and mind degenerate, slowly perhaps, but nevertheless just as inexorably.

Christians, however, don't wait for such a serendipitous wake-up call to move them beyond culture's denial. At our best, we don't evade, lie about, flee from or candy-coat the specter of death. Rather, with the Lenten practice of actively contemplating our own death, we pre-empt the inevitable. In Becker's words, adopting a phrase from Luther, the Christian seeks to ". . . . taste death with the lips of your living body [so] that you can know emotionally that you are a creature who will die."

This counsel to "remember death" was standard wisdom for the early church fathers. Gregory of Nazianzus (329–388) echoed Plato when he suggested that our present life ought to be "a meditation upon death." He advised his friend Philagrios to live "instead of the present the future, and to make this life a meditation and practice of death." To the priest Photios he wrote: "Our cares and our attention are concentrated on one thing only, our departure from this world. For this departure we prepare ourselves and gather our baggage as prudent travelers would do." In his treatise On Virginity, Athanasius (296–373) encouraged readers to "recall your exodus every hour; keep death before your eyes on a daily basis. Remember before whom you must appear." John Climacus (525–605) advised us to "let the memory of death sleep and awake with you." So too St. Benedict, who in his Rule (c. 530) advised his monks to "see death before one daily."

By contemplating my death, I live more fully in the present moment, and embrace and affirm all that is life-giving. I prepare myself for that most inevitable and important date with destiny when I will pass from time to eternity. If it is true that "at the moment of our death we will all know for certain what is the outcome of our life" (St. Gregory of Sinai, 13th century), then instead of living today in ways that death will render meaningless if not tragic, I can alter my course here and now. Anticipation, then, functions as preparation.

|

Receiving ashes in the United States. |

In his book Tortured Wonders (2004), Rodney Clapp recounts a person who chose Ash Wednesday for her one and only church appearance of the year. St. Bartholomew's Episcopal Church in New York City stands at the corner of Park Avenue and 51st Street, at the epicenter of that island's remarkable concentration of wealth, power, business, and entertainment.

One Ash Wednesday morning the priests had begun the ritual of smearing ashes on the foreheads of worshippers with the solemn words, "dust you are, and to dust you shall return" (Genesis 3:19), when a gorgeous young woman, impeccably dressed, came forward and knelt at the altar. The young woman was visibly nervous, and as she knelt the priest realized that she wanted to speak. As he leaned forward to trace an ashen cross on her forehead, she whispered, "Father, I am a model. I know I only have a few years, then I will be too old for this work. My body is aging, and I can hardly admit it to myself. I do it once a year at this service. So rub the ashes on. Rub them hard."

For further relfection

* Joan Didion, The Year of Magical Thinking (New York: Knopf, 2005), 227pp. Named one of the top five non-fiction books of 2005 by the NYTs, Didion meditates on her husband's sudden death from a massive heart attack at the dinner table.

* Julian Barnes, Nothing to Be Frightened Of (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2008), 244pp. The British novelist and atheist wonders if he can assign any meaning to his life if only extinction awaits him after death. Named one of the top five non-fiction books for 2008 by the NYTs.

Image credits: (1) SocietyofOurLady.net; (2) Life's Rich Pageant blog; and (3) Traditio; the Traditional Roman Catholic Network.