Believing the Believers:

"Public Evidence for a Mystery"

For Sunday April 8, 2007

Easter 2007

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year C)

Acts 10:34–43 or Isaiah 65:17–25

Psalm 118:1–2, 14–24

1 Corinthians 15:19–26 or Acts 10:34–43

John 20:1–18 or Luke 24:1–12

|

Three Women (Easter Sunday) by Romare Bearden (1912-1988). |

Upon his death in 1998 my dad donated his body to the University of Arizona for medical research. I loved his final, selfless, and entirely rational decision to benefit science, but I've seen cadavers and it felt ghoulish to picture a young med student dissecting his corpse. About eighteen months later FedEx delivered dad's "cremains" to our house, and I remember thinking that there had to be a better way than FedEx to return such a sacred gift. I opened the box, untied the twisty that secured the plastic liner, and verified what others had told me; these were not nice, fluffy ashes, but gritty shards of bone. I took a pinch of the coarse remnants of my father and rubbed it back and forth between my thumb and fingers.

This year Easter Sunday falls on my dad's birthday, and I've found myself resonating with Nora Gallagher's friend Harriet. In her book Practicing Resurrection, Gallagher recalls a conversation with Harriet who told her about sitting in church at the National Cathedral in Washington. During the course of a boring sermon the priest asked the congregation in unctuous tones, "Now what do you really want for Christmas this year?" "I nearly rose from my pew," she told Nora. "I was gathering myself up until I looked over at my sister who was giving me That Look, and I sat back down, but what I wanted to do was stand up and call out, 'I would really like to believe in the resurrection.'"

Doubts about the resurrection didn't begin with the eighteenth-century Enlightenment, nineteenth-century Darwinists, or with twentieth-century post-modernists. Only our modern hubris, what the British historian EP Thompson (1924–1993) called "the enormous condescension of posterity," could believe that we today have advanced beyond the crude superstitions of illiterate peasants who in 33 AD were so gullible that they didn't know that corpses don't rise from the dead. No, the readings this week show that lots of people doubted the resurrection, and not only derisive unbelievers but even Jesus's closest followers.

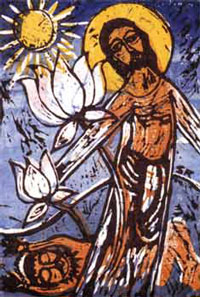

|

Resurrection, by Solomon RAJ, India. |

Women took spices and perfumes to the tomb after the crucifixion to anoint a corpse, not to witness a resurrection. When Mary Magdala saw the empty tomb she thought that someone had stolen the body: "They have taken the Lord out of the tomb, and we don't know where they have put him!" (John 20:2). She wept and cried: "They have taken my Lord away, and I don't know where they have put him. . . . Sir, if you have carried him away, tell me where you have put him, and I will get him" (John 20:13, 15). Matthew says that this stolen body scenario was "widely circulated" (28:15) in his day.

When Mary Magdala and several other women subsequently told the eleven disciples that they had seen the risen Lord, "they did not believe it" (Mark 16:11). Luke is more blunt: "They did not believe the women, because their words seemed to them like nonsense" (Luke 24:11). That first Sunday night the eleven disciples cowered behind locked doors (John 20:19), and why not? It was not unreasonable for them to fear for their own lives. Later, two witnesses reported their encounter with Jesus to the eleven, "but they did not believe them either," and even Jesus himself "rebuked them for their lack of faith and their stubborn refusal to believe" (Mark 16:13–14). Thomas became the most famous Doubter, of course (John 20:24–25), and in what might have been his last resurrection appearance there were still "some who doubted" (Matthew 28:17).

At some point, though, this widespread doubt and confusion gave way to deep-seated conviction, and history has never been the same.

Luke says that after Jesus suffered, "he showed himself to these men and gave many convincing proofs that he was alive" (Acts 1:3). The panic of these "unschooled and ordinary men" (Acts 4:13) gave way to their bold proclamation: "God has raised this Jesus to life, and we are all witnesses of the fact" (Acts 2:32). When commanded by the religious authorities to stop preaching, Peter and John replied, "We cannot help speaking about what we have seen and heard" (Acts 4:20). They claimed that they had eaten with the resurrected Jesus (Acts 10:41), and that many witnesses could attest to his public appearances (1 Corinthians 15:5–8). So, "with great power the apostles continued to testify to the resurrection of the Lord Jesus" (Acts 4:33). All their bravado would have ended easily enough if someone had produced Jesus's body, but the absence of his body and the clearly empty tomb pointed toward something far more radical than a mere spiritual or figurative resurrection.

|

Who will roll away the stone, by Hanna Cheriyan Varghese, Malaysia. |

Other people mocked and scoffed. The religious authorities were "greatly disturbed because the apostles were teaching the people and proclaiming in Jesus the resurrection of the dead" (Acts 4:2). When some Athenians heard about the resurrection, "they sneered" (Acts 17:32). Porcius Festus, the Roman governor of Judea under Nero (59–62 AD), confessed that he was "at a loss" to know what to do with the prisoner Paul: "They did not charge him with any of the crimes I had expected. Instead, they had some points of dispute with him about their own religion and about a dead man named Jesus who Paul claimed was alive." The next day as Paul gave his legal defense Festus screamed, "You are out of your mind, Paul! Your great learning is driving you mad" (Acts 25:19–20; 26:24). Peter denied the charge that he propagated a "cleverly invented tale " (2 Peter 1:16), while Paul rebutted Corinthians who said that "there is no resurrection of the dead" for anyone at all (1 Corinthians 15:12). So, there is nothing new about contemporary disbelief in the resurrection.

It's theoretically possible that the first believers were either badly deluded and wrong, or blatant liars and immoral—"deceived or deceivers," as Pascal put it (Pensees 322, 310), but neither of those explanations sounds convincing to me. The only thing they stood to gain for their beliefs was political persecution and social marginalization. Paul raised the stakes even higher when he insisted that no person should believe a lie about the resurrection, and that they certainly should not preach a lie (1 Corinthians 15:12–19); if Jesus is not raised then Christian faith is a cruel hoax and a silly fiction.

I believe the first believers partly because of their chronicle of disbelief—their own and that of their detractors, and because of the price they paid to proclaim the resurrection. To me it has the ring of truth. Peter, Paul and many other unknown and unnamed believers died in Rome because of their conviction about the resurrection. In the end, Peter challenges each one of us: "judge for yourselves" (Acts 4:19).

|

Empty Tomb, by He Qi, China. |

They knew from firsthand experience that you can't compel belief in the resurrection. On the one hand, they insisted that their message was "true and reasonable," for the events they described were "not done in a corner" (Acts 26:25–26) but could be corroborated and verified, at least at some level and for a few years. On the other hand, Paul admitted that his gospel was "to the Jews a stumbling block and to Greeks foolishness" (1 Corinthians 1:23), while Luke wrote that the resurrected Jesus "was not seen by all the people, but by witnesses whom God had already chosen—by us who ate and drank with him after he rose from the dead" (Acts 10:41). Their witness thus amounted to what the Yale historian Jaroslav Pelikan once called, oxymoronically, "public evidence for a mystery."

I believe the belief of the women who were the last at the cross and the first at the empty tomb, and the others who followed their lead down to today. Mother Teresa believed. So did Martin Luther King Jr. and Desmond Tutu. Others like Richard Dawkins and Daniel Dennett follow Festus in his condescending scorn. The Cambridge mathematician Bertrand Russell rejected the message and wrote a famous essay about his unbelief ("Why I Am Not A Christian"). The slave girl turned powerful preacher Sojourner Truth accepted it. I believe the first believers, and stand on the shoulders of other believers across time and space, who have believed, confessed and taught that God raised Jesus from the dead, and that in so doing he vanquished sin, death, and the devil. So, with readers from 210 countries who have visited this weekly webzine for the global church, I join the Easter chorus, "Christ is risen! He is risen indeed!"

For further reflection:

* What doubts do you have about the resurrection?

* Does it make sense to you that the first Christians might have been "deceived or deceivers" (Pascal)?

* What do you think Pelikan meant by "public evidence for a mystery?"

* What did you make of the Discovery Channel's March 4, 2007 show, "The Lost Tomb of Jesus?"

* Consider Paul's words that with his resurrection Jesus "destroyed death" (2 Timothy 1:10), our "last enemy" (1 Corinthians 15:26).