When the Time Came: Christmas 2005

For Sunday December 25, 2005

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year B)

Isaiah 9:2–7 / 62:6–12 / 52:7–10

Psalm 96 / 97 / 98

Titus 2:11–14 / 3:4–7 / Hebrews 1:1–4, (5–12)

Luke 2:1–14, (15–20) / 2:(1–7), 8–20 / John 1:1–14

|

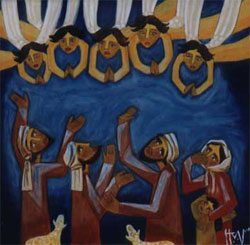

Nativity, by Hanna Cheriyan Varghese of Malaysia. |

In her poem BC:AD the British poet U.A. Fanthorpe (b. 1929), the first woman to be nominated as Professor of Poetry at Oxford University, captures the unremarkable circumstances surrounding the birth of Jesus. Nothing unusual was happening that night to break the tedium of human boredom. In the backwater municipality of Bethlehem, 1,400 miles from Rome, government bean-counters conducted a census in order to expand the tax rolls of Augustus. A few obscure shepherds stomped their feet to keep warm and gossiped to stay awake through the night shift. A mother birthed a baby. But out of that ho-hum normalcy of everyday life, Fanthorpe observes, burst a staggering paradox.

Christians celebrate that one ordinary night as the single greatest moment in all of human history.

This was the moment when Before

Turned into After, and the future's

Uninvented timekeepers presented arms.

This was the moment when nothing

Happened. Only dull peace

Sprawled boringly over the earth.

This was the moment when even energetic Romans

Could find nothing better to do

Than counting heads in remote provinces.

And this was the moment

When a few farm workers and three

Members of an obscure Persian sect

Walked haphazard by starlight straight

Into the kingdom of heaven.

|

Good News, by Hanna Cheriyan Varghese of Malaysia. |

Among the everyday affairs of ordinary people, God became a man. Eternity invaded time. Before yielded to After. God had spoken to people in many diverse ways, times, and places, but in Jesus He spoke a definitive word (Hebrews 1:1–4). In his human incarnation Jesus embodied a divine affirmation, an affirmation that God embraces all the world and everyone in it, and that He meets me in exceptional ways in all the unexceptional times and places of my ordinary life.

Luke locates the birth of Jesus in the context of normal human history, when Caesar Augustus ("the exalted") ruled as emperor of Rome during the years 27 BC to AD 14. Even more mundane, and I like to believe that Luke intended some sort of political parody here, he suggests that a pagan government's bureaucratic decree initiated the sequence of events that lead to the incarnation. God used this "exalted" earthly emperor's tax census as the occasion for the birth of the true Lord of All. Only this king of kings entered the world in an unceremonious way as we all do, as a helpless baby, in stark contrast to the pomp that characterizes the Roman emperors back then or many heads of state today.

When Quirinius, the governor of Syria, enacted the decree of Augustus, Joseph and Mary complied. Even though Mary was far along in her pregnancy, they trekked 90 miles from Nazareth to Bethlehem to register with the government. Soon after they arrived, Luke writes, "the time came" (1:6) for the most magical of all human occurrences, the birth of a baby. Although it is hard to rid our minds of images of cute kids in oversized bathrobes and towel turbans, what happened next was a combination of the commonplace and the cruel.

|

Shepherds, by Hanna Cheriyan Varghese of Malaysia. |

As was customary, Joseph and Mary wrapped the newborn Jesus in strips of cloth. But was it not pitiless that the boarders in the guest rooms could not accommodate a pregnant teenager who had begun birth contractions? This appears even more cruel if, as many scholars believe, Joseph had sought housing among his extended family. Dealt these harsh realities, Mary and Joseph "placed him in a manger," which is to say in a feeding trough used for animal fodder. Only months later the young family would escape to pagan Egypt as displaced exiles. There is no question but that Luke implies that Jesus whom Christians worship as the Messiah, the Lord, and the Savior of the world (1:11–12), entered our world as an outsider who was rejected by the insiders.

His first well-wishers were not the well-off, the connected, the powerful, or the wealthy, and certainly not state royalty. Rather, common laborers to whom God had spoken in the middle of the night worshipped Jesus. Given the rough and tumble context of his birth, these coarse shepherds were likely the only sorts of people who would have felt comfortable at Jesus's "manger." Whatever the shepherds saw or heard that night, Luke describes them as "terrified." But their terror turned to joy, and their joy turned to witness: "When they had seen him, they spread the word concerning what had been told them about this child" (1:17). From that day forward the rumor mill and the gossip mongers hit overdrive and did not stop for thirty-three years. Just who was this child? What did all the strange events portend? Like every mother who has ever given birth, Mary "treasured up all these things and pondered them in her heart," wondering what would become of her newborn son (2:19).

The Christian liturgical calendar observes special times of the year as extraordinary feasts (or fasts), times that mark exceptional moments in the rhythm of the year. The remainder of the year is relegated to so-called "Ordinary Time." But the affirmation of the incarnation is that there is no such thing as ordinary time, ordinary place, or ordinary people. Nor is there an ordinary school, soccer team, or job. There is no ordinary marriage or friendship. The implications are endless. If the son of God gasped his first baby breaths while screaming in a feeding trough, if tax decrees by pagan emperors and ruddy shepherds working in the middle of the night all played their role in the drama of salvation, then nothing is "ordinary."

|

Batik of Shepherds, by Hanna Cheriyan Varghese of Malaysia. |

Because of the incarnation, any and every dimension of life becomes an arena of God's extraordinary saving activity. Recognizing this, suggests Rowan Williams, Archbishop of Canterbury and leaders of the world's 100 million Anglicans, is the secret to living the entire liturgical year with a sense of God's presence. In the most mundane circumstances, "here we are daily, not necessarily attractive and saintly people, along with other not very attractive and saintly people, managing the plain prose of our everyday service, deciding daily to recognize the prose of ourselves and each other as material for something unimaginably greater—the Kingdom of God, the glory of the saints, reconciliation and wonder" (Where God Happens, 2005).

After all the office parties, after eating way too much food, after the kids return to college from their semester break, and after special worship services at church—all the wonderful treasures of Christmas that we rightly enjoy without apology, after all of this we return to so-called ordinary time. But even the dullest winter day shadowed by monotony can be a place where God intervenes in exceptional ways. If we look and listen carefully, we realize that like the shepherds we too can walk "haphazard by starlight, straight into the kingdom of heaven."

For further reflection:

* What is your biggest challenge as a Christian at Christmas time?

* Why do we often think that God works in the exceptional rather than in the ordinary?

* What are the salient features of Luke's narrative of the birth of Jesus?

* For what person or situation in your life would you like a fuller "affirmation of the incarnation?"