Hardest to Bear, Easiest to Forget: The Course of Human History

For Sunday July 17, 2005

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year A)

Genesis 28:10–19, Wisdom of Solomon 12:13, 16–19, or Isaiah 44:6–8

Psalm 139:1–12, 23–24, or Psalm 86:11–17

Romans 8:12–25

Matthew 13:24–30, 36–43

|

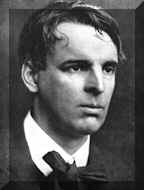

William Butler Yeats. |

Writing in the wake of the appalling carnage of World War I in which 37 million people died, the Nobel laureate William Butler Yeats (1865–1939) of Ireland articulated a grim notion of human history in his poem The Second Coming (1921). Even those who are unfamiliar with his poem will recognize some of its famously evocative lines:

Turning and turning in the widening gyre

The falcon cannot hear the falconer;

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.Surely some revelation is at hand;

Surely the Second Coming is at hand.

The Second Coming! Hardly are those words out

When a vast image out of Spiritus Mundi

Troubles my sight: somewhere in sands of the desert

A shape with lion body and the head of a man,

A gaze blank and pitiless as the sun,

Is moving its slow thighs, while all about it

Reel shadows of the indignant desert birds.

The darkness drops again; but now I know

That twenty centuries of stony sleep

Were vexed to nightmare by a rocking cradle,

And what rough beast, its hour come round at last,

Slouches towards Bethlehem to be born?

Yeats portrays human history as a maelstrom of dark impulses, grim forces, political zealotry that thwarts reasonable compromise, and the loss of innocence. A falcon spirals upward out of the control and reach of its master's voice. Hard upon the heels of failed Christian civilization, he imagines a pagan sphinx rising to life in the desert sands. The lion-man is a terrifying apparition with a pitiless, blank stare, lumbering across the scorched earth surrounded by screeching birds that sound like something out of a Hitchcock horror film. Is it any wonder that in our world of nuclear proliferation, failed states, unimaginable poverty for about 40% of the planet's people, and global terrorism, that some commentators suggest that Yeats's poem reads with as much relevance today as it did a century ago?

How will human history end? Can you imagine New York City in 3,000 AD?

|

Egyptian Sphinx. |

Christian treatments of the end of history fall into several broad categories. There are the sensational, potboiler date-setters like The Late Great Planet Earth by Hal Lindsey (the #1 non-fiction seller of the 1970s), or the Left Behind series by Tim LaHaye that has sold 75 million books and auxiliary products. I think of this genre as junk food theology. Liberal believers seem embarrassed by the subject and often appeal to agnosticism (Borg, Spong). In his short preface to the book of Revelation that appeared in 1522 and subsequent editions up to 1527, Luther complained that he found the book "neither apostolic nor prophetic," and that he could "in no way detect that the Holy Spirit produced it." So, along with Hebrews, James, and Jude, he relegated Revelation to an appendix at the end of his New Testament. After all, even if most accepted it, did not important early church fathers like Chrysostom reject its canonicity? Zwingli described Revelation as a "non-biblical book," and Calvin wrote commentaries on every book of the New Testament except for it and 2-3 John. In Eastern Orthodoxy Revelation is the only book of the Bible not read with the Divine Liturgy. Science by itself would not offer much insight about the end of history, except for the empirical truth, inherently nihilistic, that in a few billion years planet earth will be uninhabitable.

Still, the readings for this week remind us that a Christian vision of the end of history is deeply embedded in the traditions of both Jesus and Paul (not to mention John's Revelation). Eschatology is hardly a theme we should ignore or dismiss, even if we rightly insist that enlightenment temper zealous enthusiasms. Compared to Yeats who held to a cyclical view of history, the Christian scheme is decidedly linear, with a beginning (creation), a middle turning point (Jesus), and an end (the eschaton). For the believer, human history is going somewhere and not nowhere.

In Matthew's Gospel for this week Jesus compares his emerging kingdom of life and love to a field of wheat infested with look-alike weeds. That is a decidedly ambiguous and undesirable situation. He advises caution when it comes to human judgments. But there will be a harvest when noxious weeds are burned and the true grain is brought into the barns. Justice will be served, wrong will be righted, and suffering will be reversed. Similarly, Paul acknowledges the obvious. He employs sober language to describe the ambiguous history of all creation. On the one hand, and so true to our experience, he acknowledges cosmic suffering. These sufferings provoke a sense of frustration, futility, weakness, and subjugation. We remain "in bondage to decay." Like a woman in childbirth, he says, all creation groans inwardly and outwardly. The pain can feel almost unbearable. Paul is thus brutally realistic about our human condition.

|

A mushroom cloud rises 7,000 meters above Nagasaki in Japan on 9th August 1945. |

Paul also exudes confident hope. Believers should live in eager expectation, looking forward to a future glory that will far eclipse present suffering. The ultimate destiny of all of creation is liberation and freedom, adoption and redemption. The scale and scope of this future hope includes "the whole creation." There is nothing niggardly about Paul's view of the end of history. He never intimates how or when this will happen, but he never equivocates whether it will happen.

My mother, who bore six children, once described the pains of child birth as "the hardest to bear, the easiest to forget." Paul admits that his view of the end of history is an unseen hope; our penultimate view is cloudy. Much of what we do see and experience, he suggests, causes us to wonder and doubt. But at the end of the day he is the ultimate, unflinching optimist. By its very nature, you hope for the unseen rather than the seen, the Not Yet as opposed to the Already. Who hopes for what she already has, he asks? So, while we hope for what we admit we do not have or could never prove, we do so, urges Paul, with patience and confidence. In the metaphor of Yeats, the rocking cradle of Bethlehem will vanquish every ominous beast of the desert.