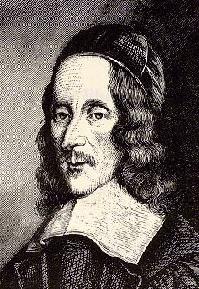

George Herbert (1593–1633)

Pastor and Poet

Week of Monday, November 18, 2002

This past summer I took a personal retreat, and among the backlog of magazines and journals that I took to catch up on, the Christian Century featured a series of favorite poems submitted by theologians.1 I wish I could say that I loved to read poetry and that I understood it. But I never read poetry, and when I do it is lost on me. As a poetically-impaired person, then, I was surprised how powerfully the first submission in the magazine's series spoke to me. Having read “Love (III)” by George Herbert several dozen times now, I pass it on to readers of the Journey with Jesus with the prayer that as you meditate upon it, God will speak to you as He did to me.

Born to a noble family in Wales, George Herbert was only three when his father died, leaving his mother (a friend and patron of John Donne) to raise him and his nine siblings. After graduation from Cambridge, he served the university as its “Public Orator,” an important post in which he gave voice to the university sentiments on public occasions. Later elected to Parliament, Herbert anticipated a distinguished career in politics and public service, but that was not to be. When King James I, some important patrons, and then his mother all died, he gave up his political ambitions to enter the parish. His friends objected, suggesting that the life of a pastor was beneath his dignity and skills as a scholar and statesman. To this Herbert replied,

It hath been formerly judged that the domestic servants of the King of Heaven should be of the noblest families on earth. And though the iniquity of the late times have made clergymen meanly valued, and the sacred name of priest contemptible; yet I will labour to make it honourable, by consecrating all my learning, and all my poor abilities to advance the glory of that God that gave them. . . . And I will labour to be like my Saviour, by making humility lovely in the eyes of all men, and by following the merciful and meek example of my dear Jesus.In 1629 Herbert became the rector at Bemerton, a small village near Salisbury, where he spent the rest of his short life.

In Bemerton he preached, wrote poetry, served the pastoral needs of his people with loving distinction, cared for the poor, and even helped to rebuild the church using his own resources. By all accounts Herbert was a deeply pious man, known in his village as “Holy Mr. Herbert.” His book, A Priest to the Temple (1652), offers practical advice to country pastors. Four years later, a month before his fortieth birthday, Herbert died of tuberculosis.

None of Herbert's poems had been published when he died, but upon his deathbed he gave them to his friend Nicholas Ferrar, asking them to be published only if they might help “any dejected poor soul.” This “little book,” as he called it, contained “a picture of the many spiritual conflicts that have passed betwixt God and my soul, before I could subject mine to the will of Jesus my Master: in whose service I have found perfect freedom.” Ferrar did publish the poems under the title The Temple, and they became an enormous success. Published in 1633, by 1680 the book had gone through 13 editions.2 The poems reflect his lifelong struggle between his privileged background and worldly ambitions as a Member of Parliament and the Cambridge faculty, and his choice to live as a poor country cleric in rural England. Today scholars esteem Herbert as one of the most skilled and important poets of his day, some even suggesting that his work surpasses that of John Donne.

For the series in the Christian Century, Ralph Wood submitted Herbert's poem “Love (III).”

Love bade me

welcome: yet my soul drew back,

Guiltie of dust and sinne.

But quick-ey'd Love, observing me grow slack

From my first entrance in,

Drew nearer to me, sweetly questioning,

If I lack'd anything.

A guest, I answer'd, worthy to be here:

Love said, You shall be he.

I, the unkinde, ungratefull? Ah my deare,

I cannot look on thee.

Love took my hand, and smiling did reply,

Who made the eyes but I?

Truth Lord, but I have marr'd them: let my shame

Go where it doth deserve.

And know you not, sayes Love, who bore the blame?

My deare, then I will serve.

You must sit down, sayes Love, and taste my meat:

So I did sit and eat.

As Wood points out, this poem is about the Lord's Supper, and more generally about the entire Christian life. Herbert pictures Christ as an innkeeper who welcomes a weary, dejected traveler. Deeply aware of his guilt and lack of gratitude, the guest finds it difficult to accept such generous hospitality. But the innkeeper reminds him that the Creator who made all of our human gifts, such as the eyes, is also the Savior who can redeem them no matter how badly we have “marr'd” them. But the traveler still wants to “bring something to the table,” as we say today, so he offers to serve the innkeeper. No, he says, the traveler must only sit down and enjoy the meal. As Wood concludes, the Lord's Supper, and by extension the Christian life, “is one Table where we are never hosts but always guests” who are unconditionally loved and encouraged to feast, no matter how unworthy we feel ourselves.

-

Ralph Wood of Baylor submitted the poem by George Herbert in the

Christian Century (July 3–10, 2002), p. 9.

- See George Herbert, The Complete English Poems, ed. John Tobin (New York: Viking Penguin Classics, 1992); and George Herbert, The English Works of George Herbert, 6 volumes, ed. GH Palmer, 1905.

The Journey with Jesus: Notes to Myself Copyright ©2002 by Dan Clendenin. All Rights Reserved.