For Sunday March 27, 2016

Easter Sunday

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year C)

Acts 10:34–43 or Isaiah 65:17–25

Psalm 118:1–2, 14–24

1 Corinthians 15:19–26 or Acts 10:34–43

John 20:1–18 or Luke 24:1–12

I hadn't planned to see the movie Risen (Sony Pictures). The film was released nation-wide on February 19 to coincide with the run-up to Easter.

The story is about an agnostic Roman centurion named Clavius who is tasked by Pontius Pilate with debunking the rumors that a crucified criminal named Yeshua had risen from the dead. It sounded like an easy job — after all, Clavius himself had given the order to spear Yeshua in the side as he hung from the cross, so all he had to do was to identify the dead body.

The Tomatometer gave Risen a paltry 57%. Metacritic registered 51%. And although I hadn't even seen the movie, that didn't stop me from resonating with the review by Peter Travers in Rolling Stone magazine (February 19, 2016): "Risen joins the swelling ranks of faith-based films that pander to audiences instead of serving them."

Nonetheless, I repressed my cinematic snootiness, and one Friday afternoon about a month ago I went to see Risen. In many ways my predisposed views were confirmed; Travers was right. And you can always quibble about the film's ratio of biblical accuracy to artistic license. I'll let you guess if there's a conversion.

But in one important regard I really liked Risen — it helped me to imagine that in real history and in real human lives something like the story about Clavius definitely happened after the death of Jesus. Rumors and denials. Fear and confusion. Doubt and incredulity. That's exactly what we read in the gospels.

|

|

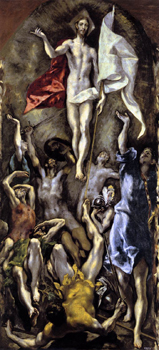

The Resurrection by El Greco, 1596-1600.

|

Disbelief didn't begin with the eighteenth-century Enlightenment, nineteenth-century Darwinists, or with twentieth-century post-modernists. Only our modern hubris could believe that we today have finally advanced beyond the crude superstitions of illiterate peasants who in 33 AD were so gullible that they didn't know that corpses don't rise from the dead.

Many people doubted the rumors of resurrection. The first to disbelieve were those closest to Jesus.

When the women told the eleven disciples that they had seen the risen Lord, "they did not believe it" (Mark 16:11). Luke is more blunt: "They did not believe the women, because their words seemed to them like nonsense" (Luke 24:11).

Later, two witnesses reported their encounter with Jesus to the eleven, "but they did not believe them either," and even Jesus himself "rebuked them for their lack of faith and their stubborn refusal to believe" (Mark 16:13–14). Thomas became the most famous Doubter (John 20:24–25), and in what might have been Jesus's last resurrection appearance there were still "some who doubted" (Matthew 28:17).

At some point, though, doubt and confusion gave way to deep-seated conviction.

There emerged a consensual tradition of "first importance" that Paul said he had received, preached, and passed on to others — that Christ died, was buried, raised on the third day, and that he appeared publicly to many people. "This is what we preach, and this is what you believed," Paul wrote to the Corinthians.

Luke says that Jesus "showed himself to these men and gave many convincing proofs that he was alive" (Acts 1:3). The panic of these "unschooled and ordinary men" (Acts 4:13) gave way to their bold proclamation: "God has raised this Jesus to life, and we are all witnesses of the fact" (Acts 2:32). When commanded by the religious authorities to stop preaching, Peter and John replied, "We cannot help speaking about what we have seen and heard" (Acts 4:20).

They claimed they had eaten with the resurrected Jesus (Acts 10:41), and that many witnesses could attest to his public appearances (1 Corinthians 15:5–8). So, "with great power the apostles continued to testify to the resurrection of the Lord Jesus" (Acts 4:33).

Their bravado would have abruptly ended if someone had produced Jesus's body, but the absence of his body and the presence of the empty tomb pointed toward something far more radical than a mere spiritual or figurative resurrection.

Others mocked and scoffed. The religious authorities were "greatly disturbed because the apostles were teaching the people and proclaiming in Jesus the resurrection of the dead" (Acts 4:2). When some Athenians heard about the resurrection, "they sneered" (Acts 17:32). Porcius Festus, the Roman governor of Judea under Nero, confessed that he was "at a loss" to know what to do with the prisoner Paul: "They did not charge him with any of the crimes I had expected. Instead, they had some points of dispute with him about their own religion and about a dead man named Jesus who Paul claimed was alive."

|

|

The Resurrection by Matthias Grunewald, 1515.

|

The next day, as Paul gave his legal defense, Festus screamed, "You are out of your mind, Paul! Your great learning is driving you mad" (Acts 25:19–20; 26:24). Peter denied the charge that he propagated a "cleverly invented tale " (2 Peter 1:16), while Paul rebutted Corinthians who said that "there is no resurrection of the dead" for anyone at all (1 Corinthians 15:12).

So, disbelief in the resurrection was part of the original story, among both the followers and detractors of Jesus.

Maybe the first believers were "deceived or deceivers," as Pascal put it (Pensees 322, 310) — either badly deluded and wrong, or blatant liars and immoral. Neither of those explanations has the ring of truth to me. The only thing they stood to gain for their beliefs was political persecution and social marginalization.

Paul insisted that no person should believe a lie about the resurrection, and that they certainly shouldn't preach a lie (1 Corinthians 15:12–19); if Jesus is not raised, then Christian proclamation is a cruel hoax and a silly fiction.

But so what? Marcus Borg liked to ask, what difference would it make in your life if Jesus was not raised from the dead? That always seemed like a strange question to me.

For Paul, the resurrection is partly personal. God "will transform our lowly bodies so that they will be like his glorious body." (Philippians 3:21). And to the Corinthians (15:53): "For the perishable must clothe itself with the imperishable, and the mortal with immortality. When the perishable has been clothed with the imperishable, and the mortal with immortality, then the saying that is written will come true: 'Death has been swallowed up in victory.'

'Where, O death, is your victory?

Where, O death, is your sting?'”

So, we have something different than Plato's immortality of an immaterial soul.

More importantly, the resurrection is cosmic. Isaiah 65 imagines a new heaven and new earth. Paul says that God in Christ will "reconcile to himself all things, having made peace through the blood of his cross, whether things on earth or things in heaven" (Colossians 1:20). He will "sum up" or "bring together" "all things in heaven and on earth" (Ephesians 1:10). "The whole creation," says Paul, "will be liberated from its bondage to decay and be brought into the glorious freedom of the children of God." (Romans 8:21).

Jesus "destroyed death" (2 Timothy 1:10), our "last enemy" (1 Corinthians 15:26). He "disarmed the powers and authorities, and made a public spectacle of them, triumphing over them by the cross" (Colossians 2:15). Jesus "tasted death for every one," and "through death he rendered powerless him who had the power of death, that is, the devil" (Hebrews 2:9,14). And so the paradox, that by death Jesus conquered death.

So, instead of Borg's cavalier question, I'm more inclined to the radical opinion of the Yale historian Jaroslav Pelikan: "If Christ is raised from the dead, nothing else matters. If he is not raised from the dead, nothing else matters."

|

|

The Resurrection by Michaelangelo, 1531-1532.

|

I believe the first believers partly because of their original disbelief, and because of the price they paid to proclaim the resurrection. Peter, Paul and many other unknown and unnamed believers died in Rome because of their conviction about the resurrection. In the end, Peter challenges each one of us: "judge for yourselves" (Acts 4:19).

But evidence and argument only go so far. You can't prove the resurrection.

On the one hand, the first witnesses insisted that their message was "true and reasonable," for the events they described were "not done in a corner" (Acts 26:25–26). They were public in nature. The story could be corroborated or refuted by people like Clavius, at least at some level and for a few years.

On the other hand, Luke acknowledges that the resurrected Jesus "was not seen by all the people, but by witnesses whom God had already chosen — by us who ate and drank with him after he rose from the dead" (Acts 10:41). Their witness amounted to what Pelikan once called "public evidence for a mystery."

I believe the belief of the women who were the last at the cross and the first at the empty tomb. I believe the first believers, and stand on the shoulders of other believers across time and space, who have believed, confessed and taught that God raised Jesus from the dead, and that in so doing he vanquished sin, death, and evil.

So, with readers from around the world and across the ages, I join the Easter chorus, "Christ is risen! He is risen indeed!"

Image credits: (1) Web Gallery of Art; (2) Web Gallery of Art; and (3) Web Gallery of Art.