From Our Archives

For other essays on this week's texts, see Debie Thomas, I Will Pour Out My Spirit (2020); Ricardo Avila, Pentecostal Praise (2017); and Dan Clendenin, From the Inspiration of the Spirit to the Institution of the Church (2011).

For Sunday May 28, 2023

Pentecost Sunday

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year A)

Acts 2:1-21 or Numbers 11:24-30

Psalm 104:24-34, 35b

1 Corinthians 12:3b-13 or Acts 2:1-21

John 20:19-23 or John 7:37-39

This Week's Essay

I once told a friend who's a film expert that when I watch a movie, I listen for a single sentence that captures the entire film. "I do the same thing," he responded, "but instead of words, I look for an image that summarizes the movie."

We Christians are people of the Book who worship the Word made flesh. It took a while, but Christians eventually also embraced images, and those images express our faith as much as our words about the Word. That's especially true on the day of Pentecost.

In his marvelous book Picturing the Bible: The Earliest Christian Art (2007), Jeffrey Spier explains how the early believers first began to use visual forms to express their faith. Art and architecture flourished in classical Greece and Rome, of course, but for several reasons Christians were slow to use images to express their faith.

|

|

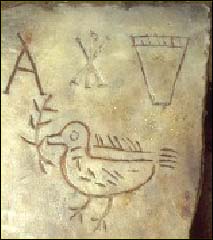

Catacomb fresco of two doves, vase, palm branches.

|

Spier writes, "no churches, decorated tombs, nor indeed Christian works of art of any kind datable before the third century are known." This might have been because the earliest Christians were a persecuted and illicit sect comprised largely of people from lower socio-economic classes. Most of them did not have the time, money, skill, or perhaps even the interest to produce art. They also inherited Judaism's ambivalence toward art that's rooted in the prohibition against graven images in Exodus 20:4. We see a similar reluctance to picture the divine in Islam.

Around the year 200, though, "purely Christian images began to appear." Most notable are the frescoes and mosaics in the forty catacombs in and around Rome, which my wife and I visited in 2016. There's also the house church at Dura Europos in Syria dated to 240 AD. These examples show how the earliest Christian art was not merely decorative but intentionally devotional. Its purpose, says Spier, was not "objective beauty" but an "expression of faith."

|

By the third century, Christian art appears on seal rings, tombs, clay lamps, engraved gems, and in one instance a marble statuette. A hundred years after that, Christian art adorns belt buckles and Bible covers, plates and coins, intricate mosaics and ornate crosses. Later still there would be the iconography of Eastern Orthodoxy, and illuminated manuscripts that combine word-and-image like the Book of Kells (c. 800), which one scholar has called "arguably the most famous book in the world."

Just as Christian art portrayed Jesus as a shepherd, fish, anchor, or a lamb, the five images in this essay show how the Holy Spirit was represented by a dove. The symbolism of the dove hearkens back to when Noah sent a dove out from the ark to see if the flood waters had receded. When the dove returned, "there in its beak was a freshly plucked olive leaf" (Genesis 8:11). At long last, peace and safety for all humanity!

In all three synoptic gospels, when John baptized Jesus, "the Spirit descended upon him as a dove" (Matthew 3:16 = Mark 1:10 = Luke 3:22). The illuminated Rabbula Gospel from sixth century Syria, like thousands of similar images thereafter, reminds us that Pentecost celebrates the descent of the dove and the peace of the Spirit into our own lives today.

The earliest Christian writers didn't say much about art and images, and Spier believes that their hostility toward visual representations has been exaggerated. Most of early Christian art drew upon well-known Bible texts like Noah, Daniel in the lion's den, Moses, Jonah, Adam and Eve, and Abraham.

|

In perhaps the earliest textual reference to Christian art, Clement of Alexandria (150–215) writes that Christian art could borrow pagan symbols as long as they were appropriate. Swords and bows would be inappropriate, he said, because they represented war and violence, but a dove was suitable, said Clement, "since we follow peace."

Truly "pentecostal" believers are people of peace and the descent of the dove. "Seek peace and pursue it," wrote the ancient psalmist (Psalm 34:14). "Make every effort to live in peace with all people," says Hebrews 12:14. "Make every effort to do what leads to peace," wrote Paul to the Romans (Romans 14:19). As followers of the Prince of Peace (Isaiah 9:6) and the "Lord of peace," we Christians wish every person "peace at all times and in every way" (1 Thessalonians 3:16). "Blessed are the peacemakers," said Jesus (Matthew 5:9).

|

"Peace I leave with you," said Jesus, "my peace I give to you." And in this week's gospel, in his post-resurrection appearance, two times Jesus tells the disciples, "Peace be with you… Receive the Holy Spirit."

There's a fascinating observation about the work of the Spirit in the life of Israel's first king, Saul. We read in 1 Samuel 10:6 that when the Spirit of the Lord came upon Saul, “he was changed into another person." This Pentecost I'm praying the Peace Prayer ascribed to Saint Francis of Assisi (1182–1226). It captures the sort of radical change into "another sort of person" for which I pray:

Lord, make me an instrument of your peace.

Where there is hatred, let me sow love;

Where there is error, truth;

Where there is injury, pardon;

Where there is doubt, faith;

Where there is despair, hope;

Where there is darkness, light;

And where there is sadness, joy.O Divine Master, grant that I may not so much seek

To be consoled as to console;

To be understood as to understand;

To be loved as to love.For it is in giving that we receive;

It is in pardoning that we are pardoned;

It is in self-forgetting that we find;

And it is in dying to ourselves that we are born to eternal life.

Amen.

We don't know the actual author of this famous prayer, and it was not until the 1920s that it was even ascribed to Saint Francis. By one account the prayer was found in 1915 in Normandy, written on the back of a card of Saint Francis. But it certainly expresses his longing to be an instrument of peace in our violent world.

In the first pages of Genesis the stuff of creation was a formless or unformed waste. A shapeless, futile, and empty void. Darkness and desolation covered the watery deep. Things were chaotic. But then a "great wind," the ruach elohim, blew over the waters.

|

|

Pentecost, the Rabbula Gospel, c. 586, illuminated Syriac Bible.

|

The simplest way to read this is a "strong and stormy wind," but translators have never been able to resist interpreting the ruach elohim as the wind, breath, or Spirit of the living God, the literal breath of all creation and of every life. Every breath that I take, each beat of my heart, is a gift of God's sustaining Spirit.

Like a tender Mother, says Genesis, the Spirit lovingly hovers, broods, or "flutters" over the watery chaos. This verb "to flutter" (rachaph) is used only two other times in the Hebrew Old Testament. In Deuteronomy 32:11, God says that when he found his people living in a "howling wasteland," he shielded, protected, and guarded them, "like an eagle that stirs up its nest and hovers over its young."

And in the Greek New Testament, the Spirit is our paraclete — our advocate, counselor and defender who comes along side of us to help, protect, encourage, and comfort us. This is in stark contrast to satanas — our hostile adversary, accuser, and "deceiver of the whole world" (for such is the literal translation of the Hebrew word).

In the earliest art of the first believers, the Holy Spirit is a dove of peace who brings God's shalom into our chaotic personal lives and our violent world. The descent of the dove brings us everything that nourishes human wholeness and well-being. Jesus called it "my peace that the world cannot give."

Weekly Prayer

Attributed to the German Benedictine monk and priest Rabanus Maurus (776–856).

COME, Holy Spirit, Creator blest,

and in our souls take up Thy rest;

come with Thy grace and heavenly aid

to fill the hearts which Thou hast made.

O comforter, to Thee we cry,

O heavenly gift of God Most High,

O fount of life and fire of love,

and sweet anointing from above.Thou in Thy sevenfold gifts are known;

Thou, finger of God's hand we own;

Thou, promise of the Father, Thou

Who dost the tongue with power imbue.Kindle our sense from above,

and make our hearts o'erflow with love;

with patience firm and virtue high

the weakness of our flesh supply.Far from us drive the foe we dread,

and grant us Thy peace instead;

so shall we not, with Thee for guide,

turn from the path of life aside.Oh, may Thy grace on us bestow

the Father and the Son to know;

and Thee, through endless times confessed,

of both the eternal Spirit blest.Now to the Father and the Son,

Who rose from death, be glory given,

with Thou, O Holy Comforter,

henceforth by all in earth and heaven.

Amen.

Dan Clendenin: dan@journeywithjesus.net

Image credits: (1) Yale Divinity Digital Image & Text Library; (2–4) JesusWalk.com; and (5) Wikimedia.org.