For Sunday June 12, 2022

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year C)

Psalm 8

Romans 5:1-5

John 16:12-15

For earlier essays on this week's RCL texts, see the two essays by Debie Thomas, The Trinity: So What and Deeper than Darkness; and two essays by Dan Clendenin, Lo Cotidiano: "The Daily Thing" and "I have much more to say to you": Lessons from a Love Story.

Michael Fitzpatrick is a parishioner at St. Mark's Episcopal Church in Palo Alto, CA. After growing up in the rural northwest, he served over five years in the U. S. Army as a Chaplain's Assistant, including two deployments to Iraq. After completing his military service, Michael has done graduate work in literature and philosophy. He is now finishing his PhD at Stanford University.

There Jesus was, forgiving people of their sins, healing the outcasts, raising the dead, passing divine judgment upon the obstinate, and revealing the Kingdom of Heaven as if he knew it personally. As those around Jesus soaked up these experiences, they began to find themselves thinking, “Wow, so that is what God is like.” It wasn’t enough to be grateful to this man for his compassion or admonitions. The way in which Jesus gave himself for others graciously led his disciples to marvel, “Here was more than just a man: here was a window into God at work” (John A. T. Robinson).

|

|

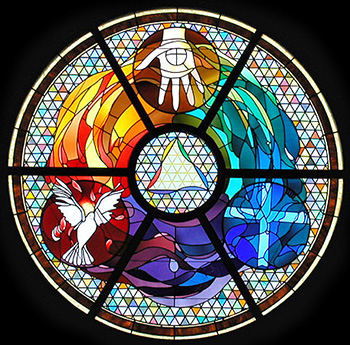

Trinity stained glass at St. Gabriel of the Sorrowful Mother in Avondale, PA. |

Yet even this was not enough. To say this is what God is like might imply that there was some part of Jesus’ life which was not what God was. Yet the disciples came to believe that watching Jesus at work wasn’t like watching God at work — it was watching God at work! One day a man cried out from the crowd for Jesus to help his son who was dying at the hands of an evil spirit. Jesus rebuked the “impure spirit” and healed the child, whereupon all the crowd was “amazed at the greatness of God” (Luke 9). God chooses the humility of a backwater Jewish peasant as the very embodiment of divine power at work in the world. Thus New Testament scholar John A. T. Robinson concludes, “The life of God, the ultimate Word of Love in which all things cohere, is bodied forth completely, unconditionally and without reserve in the life of a man — the man for others and the man for God.” As Robinson writes elsewhere, “We see not simply a man living close to God; we see God exposed, God in action as sheer grace, accepting the unacceptable, reconciling the world to himself.”

If the fullness of God was experienced in the man Jesus, does that mean God was absent in the rest of the world, abdicating the role of Creator and Sustainer while Jesus toured the beaches of Lake Tiberias? We might recall the scenario in the Jim Carrey comedy Bruce Almighty, where God (played by Morgan Freeman) grants Bruce (Jim Carrey) a week’s worth of divine responsibility for Buffalo, NY. Was Jesus up to something similar in Galilee?

By no means! The One who creates all things is not a creature. All of God was found in Jesus by those who walked with him, and yet all that God is remains transcendent beyond every relationship that makes up the fabric of the world. This isn’t because the “Father” of Jesus is distant; quite the opposite. Because God “is not served by human hands, as if needing anything,” the One who needs nothing is free to “give everyone life and breath and everything else,” that we might simply “reach out” and find that God “is not far from any one of us.” For the “Father” of Jesus is the gracious One in whom “we live and move and have our being” (Acts 17).

So the New Testament speaks of God as both “Father” and “Son” — that is, all of God is both the parent of our being and our brother beside us. It’s not that there are two gods, one above and one below; rather, there is one God, who is fully above as the “light and high beauty for ever beyond” the reach of what is shadow (The Lord of the Rings, III.6.2) and who is fully below with us in the grind, a body laboring alongside our bodies for our sakes.

|

|

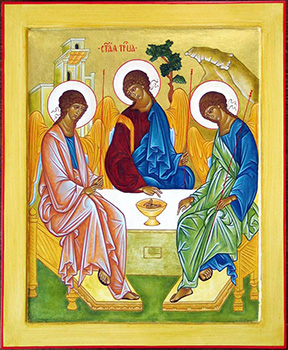

Old Testament Trinity by Russian Orthodox iconographer Andrei Rublev. |

The New Testament goes still further. The “Spirit” of this same God is discovered living in the community of Christ, both in us as a community and within each of us as individuals. Just as the first disciples looked at Jesus and found God at work, so we can look at each other and find God at work. Not, of course, that we are God, but simply to say, “I no longer live, but Christ lives in me” (Gal. 2.20). Not a part of God or a part of Christ, as if God could be divvied up and spread around like peanut butter. Nor God wearing different hats, as if God is sometimes beyond, sometimes beside, and sometimes inside. All of Christ lives within us; all of God was in Jesus the Christ; and all of God lies beyond this world ushering it forth.

To put it succinctly, God is without us, with us, and within us.

John A. T. Robinson writes, “One can say that for the Christian the deepest awareness of ultimate reality, of what for him is most truly and finally real, can only be described at one and the same time in terms of the love of God and of the grace of our Lord Jesus Christ and of the fellowship of the Holy Spirit.”

Although God is one, this one God is fully met in three distinct ways. Christians have called this “threeness” the Trinity. It’s not some abstract doctrine with no bearing on daily life; it expresses a very simple Christian idea, which the Lutheran pastor Dietrich Bonhoeffer captures neatly: “Wherever God is, God is wholly there.” If God is in Christ, then God is wholly there. If Christ is in us, then Christ is wholly there. There are no half-measures for God! God is not multi-tasking, trying to juggle being in you and in me; if Christ’s Spirit lives within us, Christ is wholly there in each of us.

For a useful analogy, think of three-dimensional space, the ordinary physical relations we experience between ourselves and other stuff in the universe. Space as we experience it has three dimensions — length, width, and depth. One dimension gets us lines, two dimensions get us squares, and three dimensions get us cubes. None of these dimensions reduce to the other (e.g., length is not width), yet these three dimensions are not three things — they are one thing (space) in three dimensions. My height is not in a different space than my width! I occupy one space, but I do it as a three-dimensional being.

God is kind of like space. God is the one, unified Creator. Just as we can’t describe our bodies properly without describing ourselves in three dimensions, so God can only be properly seen in 3-D. There is one God, but in three dimensions: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. Of course, it’s merely an analogy, and can only take us so far.

|

|

A Celtic trinity knot on the forehead of a person in the north transept of St. Mary's Church in New Ross, Ireland. The church is nearly 800 years old.

|

Likewise, the Trinity is not an attempt to eliminate the mystery of God but to help make the mystery of God real for our lives. Robinson writes, “The [Trinity] doctrine is to the experienced reality what the map is to the earth or a model for the scientist. Inevitably, it will desiccate and distort. But it is better to have a map than no map, and to have a true map than a false.” The Trinity is a true map to the boundless landscape of the Holy One.

We need all three dimensions of God; while God is wholly in each, the dimensions relate together in a unique way. In our Gospel reading for this Trinity Sunday, Jesus says that the Spirit “will not speak on his own, but only of what he hears… He will glorify me because it is from me that he will receive what he will make known to you” (John 16.13-14). The Spirit is wholly God, but not as an image of independence, blowing where she wills apart from Christ. Jesus portrays perfect harmony between himself and the Spirit because the Spirit is completely dependent on the Son for what she receives. The same is true of Jesus. In the next breath he says, “All that belongs to the Father is mine” (v. 15). Just as the Spirit speaks only what she receives, so the Son testifies, “The words I say to you I do not speak on my own authority. Rather, it is the Father, living in me, who is doing his work” (John 14.10).

These are relations of gracious giving and radical receiving between the dimensions of God. The “Father” dimension has life, but does not hoard it, instead giving life to the “Son” dimension so that the “Son” can give life to all. And the “Son” comes to live in each of us by giving life to the “Spirit” dimension. The Son and the Spirit receive so that they can give. The Trinity is about daily life, not irrelevant theories. For once we receive this life given freely to us, we can live out a Trinitarian life by giving freely of our life to others, knowing that our life is sustained by the One who is Life, and who gives Life to the full.

(All quotes by John A. T. Robinson taken from Honest to God, The Honest to God Debate, and his short essay on “The Trinity”. The Bonhoeffer quote is from his Christology.)

A Weekly Prayer

St. Patrick's Breastplate

Christ with me, Christ before me, Christ behind me,

Christ in me, Christ beneath me, Christ above me,

Christ on my right, Christ on my left,

Christ when I lie down, Christ when I sit down,

Christ in the heart of every man who thinks of me,

Christ in the mouth of every man who speaks of me,

Christ in the eye that sees me,

Christ in the ear that hears me.

I arise today

Through a mighty strength, the invocation of the Trinity,

Through a belief in the Threeness,

Through a confession of the Oneness

Of the Creator of creation.

Found in an ancient Dublin hymnal, the "Lorica" of St. Patrick is attributed to the traditional Irish saint because of its use of language and liturgy common to early Irish monasticism. The excerpt above features one of the many stages of the hymn where those chanting the prayer bind themselves to the hope of the God who was in Christ.

Michael Fitzpatrick welcomes comments and questions via m.c.fitzpatrick@outlook.com

Image credits: (1) Blogspot.com; (2) Blogspot.com; and (3) Megalithic Ireland.