For August 16, 2015

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year B)

1 Kings: 2:10-3:14

Psalm 111

Ephesians 5:15-20

John 6: 51-58

Once upon a time, there was a wise prince. Following his father's death, the prince assumed his divinely appointed throne, married a beautiful princess from a neighboring kingdom, and settled down to govern his people to the glory of God. Soon afterwards, God appeared to him in a dream, and promised to grant the young royal whatever his heart desired.

Being a humble man, the king refused to ask for wealth, power, or long life, and instead replied thus: "I am only a child. Therefore give your servant an understanding mind to govern your people, and to discern between good and evil."

God was so pleased with the king's request, he promised not only to grant it — to make this king the wisest human being in history — but to grant him every other measure of greatness as well. Untold wealth, matchless honor, and long life.

In time, the king's reputation for brilliance spread across the land. Nobles traveled from distant shores to hear his pithy sayings and witness his wise judgments. In accordance with his wisdom and God's blessing, the king's wealth and power grew beyond measure. He made strategic political and economic alliances; maintained fleets of ships; built gorgeous temples and palaces; traded in luxuries such as gold, silver, and ivory; penned the greatest wisdom literature of his time; presided over the Golden Age of his kingdom; and finally handed over the throne to his son after a peaceable reign of forty years.

|

|

|

King Solomon. 18th Century Russian icon.

|

By any measure, a "happily ever after" story.

Once upon a time, there was a shrewd prince. Following the death of the king, the prince ordered the murder of his older brother — the rightful heir — and assumed his father's throne with blood on his hands. He spent the earliest days of his reign carrying out the vengeance killings his father had requested before his death. Then, believing himself to have divine wisdom and a divine mandate, he set out to build the kingdom of his dreams — a kingdom of wealth, prestige, and power.

The king's appetites were beyond excessive. To support his extravagant lifestyle, he levied taxes his subjects could not bear. To control knowledge, he gathered the surrounding world's wisdom traditions to himself. To complete his lavish building projects, he conscripted thousands of people into forced labor. To satisfy his desires, he assembled a harem of seven hundred wives and three hundred concubines. To quell his spiritual restlessness, he constructed pagan shrines and offered worship to gods who demanded child sacrifice.

The results of his choices were dire. By the end of his reign, his people could no longer bear the crushing burdens of taxation and slavery he had placed upon them. In the wake of his paganism, they could no longer differentiate between idolatry and worship. Because he had monopolized God to justify his personal brand of wisdom, his subjects had nowhere to turn for divine discernment or reparation.

Soon the king found himself confronted by enemies. Though he attempted to fight back, God's hand was against him, and he enjoyed little success. He died shortly thereafter, denied the long life he had dreamed of. His son then tried to force the disgruntled masses back into servitude, but they resisted, and a civil war that would last for decades broke out across the land. The kingdom split in two, and the famed king's once-golden dream dissolved into chaos.

By any measure, NOT "a happily ever after" story.

So. Which story is true? Who was King Solomon? A sage or a fool? A noble or a glutton? A leader or a tyrant?

That's the first question posed by this week's lectionary reading from 1st Kings. But here's the second: What happens if the answer is yes? What if King Solomon was all of the above? What then?

I grew up in a church that espoused strict Biblical literalism and inerrancy. Though I no longer read Scripture through those lenses, I respect the challenge King Solomon poses for those who do. I have precise memories of sitting in church as a child, watching preachers twist themselves into interpretative pretzels to make sure the famed king emerged from their sermons with his reputation intact. "The wisest man who ever lived."

|

|

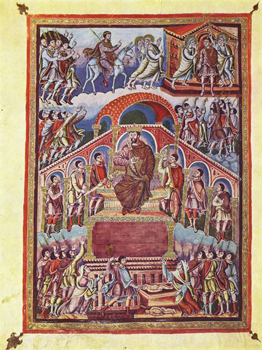

King Solomon's Court. Ingobertus, circa 880.

|

Those preachers had no choice. If the Bible literally claims that God made Solomon wiser than all the billions of human beings who ever have (or ever will) inhabit planet Earth, then the rest of Solomon's story — however sordid — must be packaged to substantiate the claim.

One way to manage the problem is to leave out huge chunks of the story, as I did at the beginning of this essay. Growing up, I didn't hear about the slaves who toiled in the king's copper mines and stone yards. Or about the excesses of Solomon's daily menu — a thousand measures of flour and meal, ten oxen, twenty cattle, one hundred sheep, and ample sides of deer, gazelle, roebuck, and fatted fowl. Or about the forbidden gods — Chemosh, Molech, Astarte, Milcom — he honored with dubious and possibly sinister sacrifices at shrines on the outskirts of the city.

Another way to revise Solomon's story is to make the time-honored, "Let's blame Eve" move. This allows Solomon to remain a wise and good king, a witty and enterprising man whose only fatal mistake is that he falls into the arms of the wrong women — foreign, idolatrous women who lead his otherwise pure heart astray.

Needless to say, this misogynistic reading depends on a pretty narrow definition of sin. Sin as sexual mishap. Not sin as greed, ostentation, fratricide, gluttony, idolatry, exploitation, or cruel indifference.

I started this essay dividing Solomon's story into two parts. The good and the bad, the noble and the shameful. But the wonderful thing about the Bible — if we're willing to liberate it from the bondage of literalism — is that it refuses to distort reality in such an unhelpful way.

The Solomon of the Bible is a human being. Which is to say, he is a paradox. Blessed with wisdom and cursed with foolishness. Devoted to God and attracted to idols. Committed to his intellect and shackled to his appetites.

We can neither whitewash nor dismiss this king — his story is too familiar. Too much like our own.

But we can learn from it. If we refuse to redeem Solomon by revision, if we're willing to look at his life in its full complexity, we can hear warnings worth heeding. They're painful and pointed warnings, but they might save us:

1. It's possible to lose God's dream in ours. Solomon may very well have received a vision from God; in the end, it doesn't matter. What matters is that Solomon's own dreams very quickly left God's in the dust. Walter Brueggemann puts it this way: "The wisdom that Solomon does not learn is attentiveness to those for whom God has special attentiveness. There are all kinds of dreams — of power and money and prestige and control. But the dream of justice for widows, orphans, and immigrants is the deep wisdom of Torah obedience." And that's the dream — God's dream for the least and most vulnerable of his children — that Solomon never fulfills.

|

|

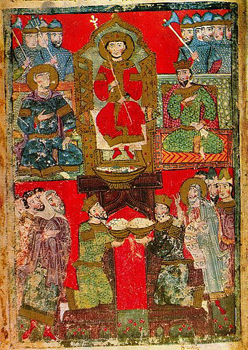

"Presents to King Solomon." A miniature from the Georgian "Jruchi Gospels". 15th century.

|

2. It's possible to hog God. A mandate is a tricky thing. Solomon believed that his wisdom and his legitimacy as Israel's ruler came from God himself. But how often, in the years that followed, did he return to that original mandate, and ask himself if his reign was still worthy of God's stamp of approval? Using God to legitimize one's own decisions and satisfy one's own lusts is dangerous, especially if it denies other people the right to appeal to God, too. I wonder, for example, how the parents of those young girls Solomon kidnapped for his harem felt about their king's "holy" mandate. Solomon monopolized God for the sake of his ambitions and appetites. He did this long after his personal devotion to God had run cold.

3. Wealth is not blessing. I feel like I need to repeat that. Wealth is not blessing. If it is, then Jesus (just to cite the obvious example) must be regarded as one of the most un-blessed people ever to walk the earth; he lived and died dirt poor. But if there's one false teaching that haunts the American church most, this is it. That money is an unambiguous sign of God's approval. Hence, prosperity theology. Hence, our willingness to turn a blind eye to sin in our politicians, our economic policy makers, our religious leaders, and our cultural icons when their sins come packaged in enormous wealth. Too often, money creates a moral vaccuum. Solomon remained wealthy while he sacrificed babies to Molech. Wealth is not blessing.

Let's try this again: Once upon a time there was a king. He had big dreams, as most of us do. He had great faults, as most of us do. He lived a life marked by success and failure, nobility and disgrace. He loved God and he didn't. He pleased God and he didn't. He left a legacy that was neither perfect nor wretched, as most of us will. But he was loved by God throughout, even when his foolish wisdom shattered God's heart. As we are.

Image credits: (1) Wikipedia.org; (2) Wikipedia.org; and (3) Wikipedia.org.