For Sunday January 17, 2021

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year B)

1 Samuel 3:1-10, (11-20)

Psalm 139:1-6, 13-18

1 Corinthians 6:12-20

John 1:43-51

I’m struggling to write this week. Sitting at my desk two days after a violent, seditious mob stormed the U.S Capitol Building at the incitement of America’s sitting president, I confess that returning to “business as usual” is difficult.

Like many of you, I am heartbroken. On the one hand, I can’t believe what my eyes witnessed on my television screen two days ago. On the other hand, I know full well that what happened in Washington, D.C was a predictable outcome of a long and reckless disregard for the truth. This is what happens when a leader and his people desecrate reality. This is what happens when human beings worship falsehood for their own convenience and gain. I know that it has become a cliché to say we live in a post-truth society — as if “post-truth” is a viable option for our survival, going forward. But the fact is, it matters what our eyes see. It matters what we apprehend as the real, the genuine, and the faithful. When truth dies, people die, too.

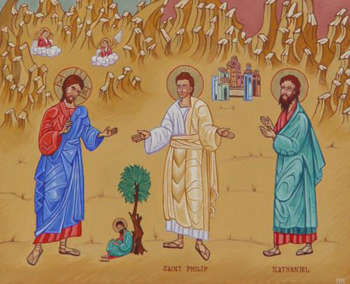

Our readings for the second Sunday after the Epiphany are all about seeing. In the book of 1st Samuel, we encounter the priest, Eli, whose physical and spiritual eyesight has grown so dim, he cannot see what’s right in front of him. The Psalmist describes a God who searches and sees us; a God who probes our secret thoughts, words, and ways; a God who beholds us when we’re still unformed “in the depths of the earth.” In his letter to the troubled Corinthians, St. Paul urges his readers to see themselves rightly, to understand that their bodies are temples of the Holy Spirit. Not cheap and expendable commodities, but sacred vessels bought at a high price for the glory of God. And in our Gospel reading, Jesus sees Nathanael — sees into his heart, sees who he is and what he needs — under a fig tree, prompting Nathanael, the skeptic, to look past his stereotypes, and see Jesus for who he really is: the Son of God.

|

As I read and re-read these texts in the aftermath of Wednesday’s events, two lines stand out to me. The first is from our Old Testament reading: "The word of the Lord was rare in those days; visions were not widespread.” And the second is from John’s Gospel: “Can anything good come out of Nazareth?”

Maybe I’m drawn to these lines right now because they echo something of my own anxieties. I have wondered this week if we — like Eli — live in an age when “the word of the Lord is rare,” and transformative “visions” of God’s just and loving kingdom are not widespread. As I watch violence and hatred erupt in my nation’s capital, I fear that nothing good, redemptive, and just can ever come from this brokenness.

But of course this isn’t true. As Christians, we profess belief in a God who never stops speaking to us. A God who longs to reveal God’s self in love, mercy, healing, and hope. Moreover, we know that God’s capacity to restore and resurrect has no limits. There is no place, time, circumstance, or situation that is beyond God’s ability to redeem. Can anything good come out of Wednesday’s atrocities? Can anything good come out of America’s endangered democracy? Yes. This is the hope we cling to. The hope we must offer to the world at this critical juncture.

But saying yes to God requires us to see rightly. It requires us to follow the truth wherever it leads — even when the truth hurts. It requires us to listen and to speak prophetically. It requires us to challenge our own assumptions about God and faith, so that we can find the sacred in unexpected and even disreputable places.

In our story from the Hebrew Bible, we meet a priest named Eli who no longer expects to see or hear anything from God. Not because God has abandoned him, but because he can’t find the courage, will, and moral fortitude to do what God desires. Eli’s sons are also priests, but they are priests who have lost their way. Priests who have made a habit of dishonoring God through extortion, greed, and sexual sin.

When Eli fails to restrain his sons, God turns to the boy, Samuel. A child on the periphery. A child whose sight and hearing remain uncompromised by the political interests and machinations of his elders. A child who will tolerate an unfamiliar voice and an uncomfortable message without holding back.

|

I’ve heard many sermons about how Samuel learns to listen for God. But I haven’t heard any about the profoundly disconcerting truth God speaks to Samuel afterwards. But think about it. God calls on Samuel to prophesy the fall of the house of Eli. Meaning, God tells Samuel to name corruption in his own religious home. To call sin out for what it is, even as that calling out upends the institution that sustains him.

What would it look like for us to do the same in this difficult cultural moment? What does truth look like now, and where and how are we being called to speak it?

Some of the most disturbing images I saw during Wednesday’s attack were images of mobsters carrying Christian signs and symbols into the Capitol Building. “Jesus Saves.” “God, Guns & Guts Made America, let’s keep all three.”

I am tempted, like many “progressive” Christians, to simply disavow such images, and move on as if they have nothing to do with me. What would it be like instead to ask a harder and more painful set of questions? Questions like:

How has the progressive church in America failed in its prophetic duty to represent the Jesus of love, mercy, hope, and restorative justice in the public square, such that we’ve allowed Christianity to be co-opted in violent, hateful ways that grieve the heart of God?

Where are the blind spots in our theology that allow white supremacy, bigotry, nativism, and populism to fester unchecked?

Are we enamored of power? Of proximity to power? Of approval from the powers?

How have we privileged personal piety over communal responsibility, such that we spend more time agonizing over what we believe about God’s grace, than we do embodying that grace to the world outside our church doors?

|

Epiphany is a season of light and revelation, a season of searching, discovering, finding, and knowing. I wonder what we can learn from the penetrating and grace-filled vision of God in these days. If Jesus were here right now, looking at what we’re looking at, what would he see?

In our reading from John’s Gospel, we encounter a skeptic named Nathanael who thinks he knows exactly who God is and how God operates. God’s Messiah, he is sure, can’t possibly come from a backwater town like Nazareth. Nazareth isn’t good enough for the divine.

The lection begins with Jesus going to Galilee, finding Philip, and inviting him to “follow me.” Philip accepts the call without hesitation, and then, brimming with excitement, runs off to find his friend, Nathanael. He finds him sitting under a fig tree. “We have found him about whom Moses in the law and the prophets wrote, Jesus son of Joseph from Nazareth!” Philip tells Nathanael. But his friend under the fig tree isn’t impressed; his religious assumptions won’t allow him to see anything fresh or surprising in a simple carpenter from the wrong side of the tracks. Instead of arguing with Nathanael, though, Philip simply tells his doubtful friend to “come and see."

When Nathanael does so, he receives the shock of his life. As soon as he and Jesus see each other, before they exchange a single word, Jesus says, “Here is truly an Israelite in whom there is no deceit!” And, “I saw you under the fig tree.”

Immediately, Nathanael moves from doubt to faith, from ignorance to knowledge. He experiences an epiphany.

But this story at its core is not about what Nathanael sees; it’s about what Jesus sees. It’s a story about Jesus’s way of looking and seeing, and about what becomes possible when we dare to experience his gaze. In this story, what makes salvation possible is not what Nathanael sees in Jesus, but what Jesus sees in Nathanael.

Seeing, of course, is always selective. We have choices when it comes to what we see, what we prioritize, what we name, and what we call out in each other. The selves we present to the world are layered and messy, and it takes both love and patience to sift through those layers and find what lies at the core of who we each are. But there is great power in that sifting, too. Something healing, something holy, something life-changing happens to us when we are deeply seen, known, named, and accepted.

Jesus had a choice when it came to seeing Nathanael. I wonder what would have happened if, instead of calling out Nathanael’s purity of heart, Jesus had said, “Here is a cynic who is stunted by doubt,” or “Here is a man who is governed by prejudice,” or, “Here is a man who is blunt and careless in his words,” or, “Here is a man who sits around, passive and noncommittal, waiting for life to happen to him.”

Any one of those things might have been true of Nathanael. But Jesus looked past them all to see an honesty, a guilelessness, a purity of thought and intention that made up the true core of Nathanael’s character. Maybe the other qualities were there as well, but would Nathanael’s heart have melted in wonder and joy if Jesus saw and named those first? Or would Nathanael have withdrawn in shame, fear, despair, and embarrassment? Jesus named the quality he wanted to bless and cultivate in his would-be follower, the quality that made Nathanael a person of beauty, an image-bearer of God.

Is it possible for us to see our present moment as Jesus sees it? Instead of deciding that we know everything there is to know about the political “others” in our lives, can we ask God for fresh vision? Instead of assuming that “nothing good” can come of the cultural mess we find ourselves in, can we accept Philip’s invitation to “come and see?” What would happen if we left our comfortable vantage points, and dared to believe that just maybe, we have been limited and hasty in our original certainties about each other, about God, and about the world? To “come and see” is to approach all of life with a grace-filled curiosity, to believe that we are holy mysteries to each other, worthy of further exploration. To come and see is to enter into the joy of being deeply seen and deeply known, and to have the very best that lies hidden within us called out and called forth.

I write these words in hope. In fragile hope, but hope nonetheless. Not because we’re capable of clear vision on our own, but because we are held by the eternal promise of Jesus who said: “You will see greater things than these.” We will. We will see heaven open. We will see angels. We will see the love and justice of God. So don’t be afraid. Don’t hide. Don’t despair. Live boldly into the calling of Epiphany. See. Name. Speak. Bless. God is near and God is speaking. Many good things can come out of Nazareth.

Debie Thomas: debie.thomas1@gmail.com

Image credits: (1) Michael_K_Marsh; (2) Dust Off the Bible; and (3) Wikipedia.org.