For Sunday July 19, 2020

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year A)

Isaiah 44:6-8

Romans 8:12-25

Matthew 13:24-30, 36-43

One of the great gifts of Christianity is that it is steeped in paradox. Every facet of the religion, from its theology, to its ethics, to its holy book, to its founder's own identity, invites us to occupy holy in-between places, places of hard but life-giving ambiguity. Yes, I know: paradox doesn’t always feel life-giving. Most of the time, we want simple, black-and-white clarity in our lives, and we try to pummel Christianity into giving it to us. But God won’t be pummeled. Despite our preferences, God gifts us with rich and rigorous contradiction:

God is One, and God is Three.

Jesus is God and Jesus is human.

The Bible is God's Word, and the Bible is authored by flawed humans.

Creation is good, and Creation is broken.

To give is to receive.

To die is to live.

To pardon is to be pardoned.

To be weak is to be strong.

To serve is to reign.

We're saved by grace, and faith without works is dead.

We are in the world but we are not of the world.

The kingdom of God is coming, and the kingdom of God is here, within us.

My list is far from exhaustive, but hopefully it demonstrates how central paradox is to Christianity. Paradox is woven right into its fabric. At every point, Christianity calls us to hold together truths that seem bizarre, nonsensical, counterintuitive, and irreconcilable. And yet these seeming contradictions are what give the religion heft, credibility, and verisimilitude. If I live in a world that's chock full of contradiction, then I need a religion robust enough and complex enough to bear the weight of that messy world. I need a religion that empowers me, in Richard's Rohr's beautiful words, "to live in exquisite, terrible humility before reality."

But what does it mean to see by the light of paradox? I think it means training our eyes to gaze at uncertainty without flinching. I think it means teaching our souls to love the "both-and," the in-between, the mystery.

This isn't easy, especially for those of us who grew up believing that Christianity is a Twelve-Step plan, or a sure-fire formula for prosperity, or a set of holy propositions requiring our intellectual assent. I don't think it's a coincidence that many of the heresies that have rocked orthodox Christianity over the past two thousand years have grown from an unwillingness to sit with paradox: Jesus can't be fully God and fully human, so let's choose one. God can't be immanent and transcendent at the same time, so we'll emphasize one attribute over the other. It can't be the case that the God of all riches favors the poor, so let's preach prosperity theology. It can’t be possible that a holy God is okay with human pleasure, so let's teach austerity.

|

It takes courage to say, "This is true — and this is true also. I don't know how, but God does, and God will show me new and beautiful things if I'll venture into the tension of this both-and, and wait for more light, more wisdom, more truth."

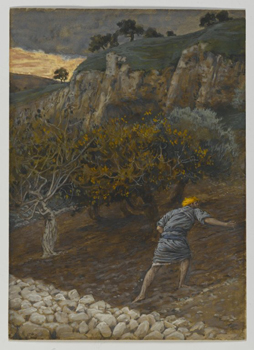

In our Gospel reading this week, Jesus invites us to practice just this kind of courage. A householder plants seeds in his field, Jesus tells the crowds in yet another agricultural parable. But while everyone is asleep, an enemy sneaks onto the field, sows weeds among the wheat, and goes away. When the plants come up, the householder’s servants are baffled. “Master, did you not sow good seed in your field?” they ask him. “Where did these weeds come from?” The householder doesn’t spare them the truth: “An enemy has done this." But when the servants offer to tear up the weeds, the householder stops them. “No, for in gathering the weeds you would uproot the wheat along with them. Let them both grow together until the harvest. At harvest time, I’ll instruct my reapers to collect, bundle, and burn the weeds, and then I’ll gather the wheat into my barn.”

As I sit with this parable, I see Jesus asking his followers to hold two seemingly contradictory truths in uncomfortable tension. One: evil is real, noxious, and among us. And two: our response to evil must include both acknowledgment and restraint.

Evil is real, noxious, and among us: For many progressive Christians, this is the harder of the two truths to swallow. After all, “evil” is such an old-fashioned, heavy-duty sort of word. It has an ugly history within the Church, a history of exclusion and wounding. Isn’t it time we dispensed with such draconian language in favor of something softer? Gentler? More enlightened? Do we really need to call anyone or anything evil?

For what it’s worth, Jesus doesn’t share our squeamishness. He states without flinching that evil is real, insidious, intentional, and dangerous. Evil in the parable of the wheat and the weeds is not a mistake. It’s not an accident or an unfortunate fluke. The weeds Jesus describes are intentionally sown into the field by a real enemy whose motivations are loveless and sinister. Moreover, the literal weeds (which many scholars believe is darnel — “false wheat” — or Lolium temulentum) are not harmless — they’re poisonous. They mimic the look and color of nourishing grain, but they’re fake, and their seeds can cause illness and even death if consumed in large quantities.

|

In other words, there is nothing enlightened about denying the reality of evil in our world and in our midst. We are, like the field in the parable, both mixed and messy. Each of us individually, our faith communities corporately, and our world in its entirety, contain wheat and weed, good and evil, the fruitful and the poisonous. We are each, in Martin Luther’s famous words, “simul justus et peccator.” At the same time both sinner and saint. To confess this is not to be draconian or puritanical — it is to be discerning and wise. It is to live in reality. And it is to believe Jesus.

But there is more to be gleaned about evil from this parable than the fact that it is real and harmful. Jesus also says without apology that evil is doomed: “At harvest time, I’ll instruct my reapers to collect, bundle, and burn the weeds.” And again: “At the end of the age, the Son of Man will send his angels, and they will collect out of his kingdom all causes of sin and all evildoers, and they will throw them into the furnace of fire, where there will be weeping and gnashing of teeth.”

Again, this is not a truth that sits well with many of us in the 21st century. Perhaps we need to ask ourselves why. If this parable offers unequivocally good news for the world’s most downtrodden, disenfranchised, tormented, wounded, and oppressed, then why are we uncomfortable with its sweeping promise? What does our discomfort say about us? About our location, vis-a-vis injustice, oppression, cruelty, and suffering? What version of divine “love” are we preaching if it doesn’t include a finale of justice for the world’s most broken and desperate people? What is compassion, in the end, without justice? Without an embodied realization of the good and the whole and the restored and the abundant? If there will never be an actual making right for the most victimized among us, then what is the Gospel, and why are we bothering with it? What is the Good News of Christianity?

In his ultimately eschatological parable, Jesus promises his listeners that justice is both necessary for an abundant harvest, and certain because God wills it. Yes, the weeds may win out in this lifetime — Jesus doesn’t deny the grim reality of life here and now. Evil may claim victory for many seasons, lifetimes, and generations. But the passionate, protective, and deeply righteous love of God will not suffer evil to rule the world forever. Oppression will end. Injustice will die. The wheat will thrive and the weeds will not. “All causes of evil and all evildoers,” Jesus says, will be exposed and disempowered. All causes of evil. The causes we condemn in others, and the causes we complacently excuse in ourselves. The causes that are personal, and the causes that are systemic. The causes we know about, and the causes we don’t. All causes of evil. No exceptions.

In short, all that chokes, starves, breaks, distorts, poisons, and harms God’s beloved, will burn away. Not because God hates the world. But because God loves it.

Our response to evil must include both acknowledgment and restraint. I have to laugh at the earnestness of the householder’s servants in this parable, because it mirrors my own. Like the servants, I tend to get worked up about weeds. Weeds in my own life, and — even more so, if I’m honest — weeds in other people’s lives. I tend to get eager and preachy and passionate. Zealous for the purity of the field. Possessive about the integrity of the householder. Impatient for a quick, clean harvest.

|

Also, like the servants, I tend to lead with confidence rather than humility when it comes to moral gardening: “Jesus, trust me, I know how to separate the weeds from the wheat. Let me at it, please, and I’ll have that field cleared for you in no time! Let’s get the work over with now — why wait? Let’s settle the question of who is good, and who is bad. Who belongs, and who does not.”

But Jesus says no. “No” and “wait.” Jesus insists on patience, humility, and restraint when it comes to patrolling the borders of his precious field. He asks us, even as we acknowledge the pernicious reality of evil, to accept his timing instead of ours when it comes to destroying it. Why? Because he knows, as Barbara Brown Taylor puts it so clearly, that the business of discernment is much harder than we think it is: “Turn us loose with a machete and there is no telling what we will chop down and what we will spare.”

In other words, there is no way we can police the wheat field without damaging the wheat. There is no way we can rid ourselves of everything bad without distorting everything good. When we rush ahead of God and start yanking weeds left and right, we do terrible harm to ourselves and to the field. Our sincerity devolves into arrogance. Our love devolves into judgment. Our holiness devolves into hypocrisy. And the field suffers.

The fact is, the seeds of God’s life in us are still young and growing. Our roots are delicate and tender, and they need time. They need lifetimes. This is not to say we should ignore evil. But it is to say that we should move gently and with great care, recognizing that our task is to grow the good, not burn the bad. Our job is to bless the field, not curse it. Remember, the field is not ours, it is God’s. Only God knows it intimately enough to tend it. Only God loves it enough to bring it safely to harvest.

So once again we are called by Jesus to a complicated in-between. A paradox. Evil is real, noxious, and among us, and our response to evil must include both acknowledgment and restraint.

If this ambiguity worries you, then remember that we are held and braced by a God who is too big for thin, one-dimensional truths — and this is a good thing. It's not that we hold paradox; it's that paradox holds us. We are held in a deep place. An ample place. A generous, sufficient, and roomy place. Though we might fear paradox, God does not, and it is in God’s soil that we are firmly planted. We’re safe, even in the contradictions. Messy and weedy for sure, but safe.

Debie Thomas: debie.thomas1@gmail.com

Image credits: (1) dbrockmanw.com; (2) Wikimedia.org; and (3) BYU New Testament Commentary.