For Sunday July 5, 2020

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year A)

Zechariah 9:9-12

Psalm 145:8-14

Romans 7:15-25a

Matthew 11:16-19, 25-30

A few weeks ago, my son asked me a question about my faith — a question I haven’t stopped thinking about since. The context for his asking was the eruption of nationwide protests against racial injustice in the wake of George Floyd’s murder. “What is the difference between your Christianity and your progressivism?” he asked. “What does being a Christian give you that being a good person — committed to equality and justice and compassion — does not?”

The question merited all sorts of answers, and I gave my son several. Being a Christian gives me hope, I said. Hope for this life and for the life to come. Being a Christian assures me that I am known and loved by a generous, self-giving God. Being a Christian means that I’m not alone when I suffer; I’m accompanied by Jesus, who has experienced pain, loss, betrayal, and death. Being a Christian reminds me that I live in a created world — a world that is sacred and meaningful, shot through with God’s artistry. Being a Christian gives me a distinct sense of purpose and vocation — to do justice, and love mercy, and practice humility before God and other people.

I liked these answers when I offered them, and I like them still. They feel real and solid and true. But as I continue to ponder my son’s question, they strike me as inadequate. As incomplete. Because there is something else, something sharper and harder-edged, something more challenging and less comfortable, that distinguishes Christianity from any kind of generic “goodness” or “niceness” I might claim.

In fact, it’s the very concept of “niceness” that an honest engagement with Christianity calls into question. What does being a Christian give me that being a “good person” does not? It gives me my sinfulness. Or rather, my Sinfulness. Capital “S.” As ironic as it may sound, Christianity liberates me with a truth that cuts before it heals: the truth that Sin is a deadly, destructive force against which I am helpless and powerless — apart from the death and resurrection of Jesus. Christianity gives me the robust and unflinching language I need to confess what St. Paul so honestly articulates in our reading from the epistle to the Romans this week: “I do not understand my own actions. For I do not do what I want, but I do the very thing I hate.” “For I delight in the law of God in my inmost self, but I see in my members another law at war with the law of my mind, making me captive to the law of sin that dwells in my members. Wretched man that I am! Who will rescue me from this body of death?”

| |

I don’t know many people — religious or secular — who cherish the word "sin." Many Christians, particularly those of us who have left various forms of fundamentalism, actively mistrust the "S" word. We associate it with guilt, shame, punishment, and hellfire. We find it too harsh, too debilitating, too unsophisticated, and too Puritanical for the complexities of our 21st century lives. Sin has become a word that jerks us away from God, instead of drawing us into God’s arms.

Moreover, we’re jaded because we’ve heard our faith leaders emphasizing certain sins over others, based on little more than their political, cultural, or sectarian biases. Some of us grew up hearing that dancing, drinking beer, and having sex before marriage are egregious sins, while abusing our planet, denigrating our non-Christian neighbors, and accruing wealth at the expense of others, are not.

Or else, we dislike the concept of sin because it offends our sense of autonomy and personal responsibility. We’d much rather believe that living good, decent lives is a matter of hard work and sheer willpower, than confess — as Paul does — that sin is an aggressive, demonic power that enslaves us even when we’re convinced of our own decency and piety. We’d much rather say that we individually “make mistakes,” or “choose poorly,” or “take wrong turns once in a while,” than admit that sin as Scripture describes it is systemic and structural, a cosmic power so insidiously at work within us that it twists and deforms us both as individuals and as societies. We’d much rather draw sharp, black-and-white distinctions between our goodness and someone else’s badness, than recognize that we’re all in the same boat, and sinking.

After all, what could be more offensive to our individualistic, compulsive, and perfectionistic sensibilities than the news that we are all puny and powerless, in desperate need of help from the outside?

A few years ago, I read a news article about Silicon Valley (where I live), in which a high school student compared us northern Californians to ducks swimming in a pond. Our movements, she wrote, appear smooth and easy at all times. We glide, we part the water, we splash and play and thrive. No one (we make sure), ever peeks beneath the surface. No one sees the truth. The effort, the frenzy, the exhaustion. The constant, furious paddling.

All of this is unfortunate, because in fact, Christianity’s conception of sin is so liberating, we dismiss it at our peril. As theologian Barbara Brown Taylor puts it: “Abandoning the language of sin will not make sin go away. Human beings will continue to experience alienation, deformation, damnation and death no matter what we call them. Abandoning the language will simply leave us speechless before them, and increase our denial of their presence in our lives. Ironically, it will also weaken the language of grace, since the full impact of forgiveness cannot be felt apart from the full impact of what has been forgiven.”

|

Embracing Paul’s vulnerable take on sin gives us a viable place to begin, a freeing place to stand. It tells us the truth, which is that we are both beautiful and broken, made in God's divine image, but enslaved to something that actively wars against our efforts to be good and do good. To use the word "sin" is to insist on something more profound and more clarifying than, "I make mistakes," or "I have issues." To use the word sin is to understand that we need Jesus to be more than a good role model, life coach, or mentor. We need Jesus to save us — to break an ancient and malevolent power we cannot break by ourselves. To use the word sin is to stop the desperate paddling, and admit at last that we cannot cross the vast water alone. To confess, as Paul does, that we are “wretched” in the face of sin’s power, and lost without the cross.

Lutheran pastor Nadia Bolz-Weber puts it this way: “No one is climbing the spiritual ladder. We don’t continually improve until we are so spiritual we no longer need God. We die and are made new, but that’s different from spiritual self-improvement. We are simultaneously sinner and saint, 100 percent of both, all the time.”

In our Gospel reading for this week, Jesus describes children sitting in the marketplaces and calling to each other with songs that no one understands. When they sing happy songs, no one dances. When they play dirges, no one mourns. When John the Baptist comes along and preaches an austere message of repentance, his listeners say he’s demon-possessed. When Jesus comes along, eating, drinking around a common table, his listeners call him a glutton and a drunkard.

In other words, when we’re left to fend for ourselves, we routinely miss what really matters. We don’t know when to dance, when to mourn, when to repent, when to celebrate. We claim to be wise and discerning, but we don’t recognize the divine when we encounter it. God is always too much or too little for us; too severe or too generous, too demanding or too provocative. On our own, we have little capacity to discern what is good and right and holy and true. “When I want to do good,” Paul writes, “evil lies close at hand.”

|

So what hope do we have? Who will rescue us from these bodies of death? Jesus concludes his parable of the children in the marketplace with some of the most comforting words in the New Testament: “Come to me, all you that are weary and are carrying heavy burdens, and I will give you rest. Take my yoke upon you, and learn from me; for I am gentle and humble in heart, and you will find rest for your souls. For my yoke is easy, and my burden is light.”

Notice that the offer of a lighter burden is not extended to the powerful and the seemingly self-sufficient. It is offered to the weary and the burdened. It is offered to those who recognize that they just can’t make it on their own, no matter how hard they try. It is offered to those who, like Paul, long to be delivered from forces too terrible to wield or manage: “Wretched man that I am! Who will rescue from this body of death? Thanks be to God through Jesus Christ our Lord!”

The next time my son and I return to his question, I will talk about Sin. I will talk about sin so that I can talk about salvation. About the gentleness, humility, and solace of Jesus, whose burden, as it turns out, is the only one light and restful enough for me to bear.

Debie Thomas: debie.thomas1@gmail.com

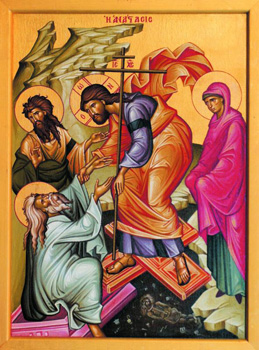

Image credits: (1) Uncut Mountain Supply; Traditional Icons Books and Gifts; (2) Holy Cross Orthodox Church, Roseburg, Oregon USA; and (3) Wikipedia.org.