For Sunday March 8, 2020

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year A)

Genesis 12: 1-4a

Psalm 121

Romans 4:1-5, 13-17

John 3:1-17

John 3:16 was the first Bible verse I memorized as a child. In Sunday School, I learned that it’s essentially Christianity 101 — a simple formula for faith, a handy evangelism tool, and a perfect summary of the Good News. Over the years, I’ve seen the verse displayed on billboards, t-shirts, coffee mugs, and cross-stitch samplers. Martin Luther called it “the heart of the Bible, the Gospel in miniature.”

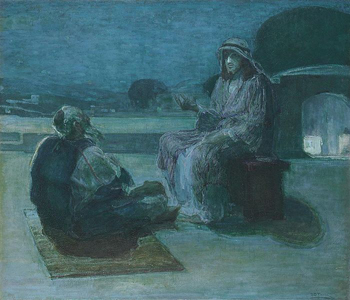

And so it is. On this second Sunday of Lent, as we consider Jesus’s lengthy, nighttime encounter with Nicodemus, John 3:16 jumps out of their perplexing dialogue for its efficiency and pithiness. In just twenty-seven words, the verse describes a loving God, a cherished world, a self-giving Son, a universal invitation, a deliverance from death, and a promise of eternal life. Christianity in a nutshell, right?

Well, I’m not so sure. The problem is not in the verse itself, but in what the Church so often does with it. In our well-intentioned efforts to make the Gospel message accessible and palatable, we Christians sometimes reduce salvation to a soundbite, forgetting that when Jesus originally spoke the words to Nicodemus — a Pharisee, a member of the Sanhedrin, and likely one of the more erudite men of his day — his listener found Jesus’s words incomprehensible. “How can these things be?” Nicodemus asked in astonishment, when Jesus spoke to him in the obscure and metaphorical language of birth, flesh, water, and spirit. But Jesus, unfazed by the Pharisee's confusion, refused to simplify his explanation. If he intended to “save” Nicodemus quickly and easily that night, he failed. What the seeker experienced was not salvation; it was bewilderment.

If Jesus’s conversation with Nicodemus is representative of God’s preferred “evangelism style,” than I have to wonder: what does my more formulaic approach to Christianity leave out? Am I so invested in keeping the faith cozy and comfortable that I minimize its weirdness? Its otherness? Its offensiveness? Jesus had no problem leaving Nicodemus confused and muddled. He was in no hurry to get Nicodemus to sign on the dotted line. The Spirit “blows where it chooses,” Jesus said. The Spirit cannot be caged or contained. Which means the journey of faith and the workings of salvation can’t be caged or contained, either. When we speak of God’s kingdom, we are in a realm of deep mystery. It’s okay to be surprised. It’s okay to be stricken. It’s okay to take our time.

|

After all, what Jesus was offering Nicodemus was not a tune-up, or a few minor tweaks to an already near-perfect life; it was a brand new life. A new birth. A fresh, down to the foundations beginning. What newborn enters the world without birth pangs, shock, disorientation, or pain? Downright bewilderment isn’t the exception in a birth story; it’s the rule. If we don’t find Christianity at least a little bit confusing, then perhaps it’s not Christianity we’re practicing.

As I sit with Nicodemus’s baffled reaction to Jesus, here’s what I’m asking myself: what does my glib reading of John 3:16 prevent me from seeing about God, Christ, faith, sin, and salvation? Do I lean too hard on the importance of individual belief, and forget the stunning truth that God loves and longs for all of creation – quite apart from my belief or unbelief? Do I treat Jesus’s words as a litmus test, using it not to communicate God’s all-encompassing compassion and mercy, but to threaten unbelievers with God’s judgment? Do I allow my interpretation to flatten and distort the meaning of “belief,” reducing its nuance and complexity to mere intellectual assent? What does it mean, after all, to say, “I believe in Jesus?” Why is “belief,” of all things, so important to God?

Growing up, I was taught that being a Christian means affirming the right things. To accept Jesus into my heart, to be "born again," was to agree to a set of doctrines about who Jesus is and what he accomplished through his death and resurrection. To enter into orthodox faith was to believe that certain theological statements about God, Jesus, the Holy Spirit, the human condition, the Bible, and the Church, were true. When we spoke of “growing in the faith,” what we meant was that we were honing our doctrinal commitments. To be a mature Christian was to have one's theological ducks in a row.

This honing, moreover, was a serious business. As a teenager, I watched congregations split up over the legitimacy of infant baptism over "believer's" baptism. I knew Christians who considered speaking in tongues a litmus test for faith. I heard pastors fight over whether the Communion table should be open (available to all) or closed (reserved for baptized members of a particular faith community). I heard others argue over the most nitpicky details concerning the “endtimes.” Would God take his children to heaven before the “great tribulation?” Or would they have to hang around and endure the birth pains of a new kingdom?

|

For the earnest and well-meaning people involved, none of these questions were silly or peripheral; they cut to the heart of what it means to be Christian. Getting the theological particulars right was paramount — what else could faith entail, if not fidelity to the correct particulars?

I fear that I fall into the same trap when I speak glibly of John 3:16 as “Christianity in a nutshell.” “For God so loved the world that he gave his only Son, so that everyone who believes in him may not perish but may have eternal life.” It sounds so gorgeously precise, so deceptively simple. But does all of Christianity really come down to my accepting certain propositions about Jesus to be factual? To be true? Is that really it?

For me, this way of believing — this way of defining faith as an intellectual assent to precisely codified doctrines — has fallen apart. Not because I can't assent, but because my assenting, in and of itself, hasn’t fostered anything close to the meaningful relationship I desire to have with God. If anything, my intellectual assent has functioned as a smokescreen. A distraction. A substitute.

In her 2013 book, Christianity after Religion, historian Diana Butler Bass points out that the English word "believe" comes from the German "belieben" — the German word for love. To believe is not to hold an opinion. To believe is to treasure. To hold something beloved. To give my heart over to it without reservation. To believe in something is to invest it with my love.

This is true in the ancient languages of the Bible as well. When the writers of the Hebrew Bible and the New Testament wrote of faithfulness, they were not writing about an intellectual surrender to a factual truth. They were writing about fidelity, trust, and confidence. As they saw it, to believe in God was to place their full confidence in him. To throw their whole hearts, minds, and bodies into his hands.

The fact is, I can't think of any significant human relationships in which doctrine matters more than love and trust. So why should my relationship with God be any different?

|

What does it mean to believe in Jesus? To hold onto him? To trust him with my life? For Nicodemus, it meant starting anew, letting go of all he thought he understood about the life of faith. It meant being “born again,” becoming a newborn, vulnerable, hungry, and ready to receive reality in a brand new way. It meant coming out of the darkness and risking the light. None of this could be reduced to an altar call or a litmus test. The work of trusting Jesus was mind-bending, soul-altering work — it was hard, and it took time, and it involved setbacks, fears, and disappointments. No wonder Nicodemus walked away baffled that first night. Jesus was calling him to so much more than a rote recitation of the sinner’s prayer; he was calling him to fall in love, and stay in love. Why is belief important to God? Because love is important to God. To believe is to be-love.

“Christianity in a nutshell” sounds catchy, but in the end, I don’t think it exists. I also don't think easy answers or efficient soundbites will serve us well during this season of Lent. After all, we're in the desert now. The wilderness. Wandering, thirsting, yearning, waiting, and listening go with the territory.

Yes, John 3:16 is a beautiful passage of scripture, and we are right to recite it, memorize it, and cherish it. But the way of faith it points to is as vast and mysterious as all the workings of a human heart reaching out for God’s. That’s why we can trust it; its challenge corresponds to reality. No love as rich, demanding, costly, and free as God’s love for us can ever be reduced to a formula.

Debie Thomas: debie.thomas1@gmail.com

Image credits: (1) Wikimedia.org; (2) Wikimedia.org; and (3) The Archives Near Emmaus.