For Sunday May 27, 2018

Trinity Sunday

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year C)

Psalm 29

Romans 8: 12-17

John 3:1-17

I was watering plants on my patio a few weeks ago when my neighbor’s son — an 8th grader — peeked over the fence and started telling me about his recent Bar Mitzvah celebration. After we’d chatted for a bit about the party, the guests, and the “awesome” gifts he’d received, he asked, “Your family is Christian, right?”

“Yes,” I said. “Born and raised.”

“Why do Christians believe in three gods?” His tone was solemn and earnest.

“We don’t. Actually, we believe in the same God you do. Just… differently.” This was a lame answer, I knew, but I hoped sort of desperately that it would suffice.

It didn’t. “No,” he pressed on. “I mean the Father, Son, and Holy Ghost thing. That’s Christian, isn’t it?” He looked at me with a truly puzzled expression. “I don’t get it.”

“Neither do I, honey,” was what I wanted to say. But he looked so genuinely bewildered that I sighed and fumbled my way through all the inadequate explanations I’d heard as a kid: “God is sort of like water! Water exists in three states, right? Liquid, solid, and gas? God’s like that! Or, like an egg! The shell, the eggwhite, and the yolk? Three parts, one egg! Or, um, a three-leaf clover! Or a tree! The roots, the trunk, and the branches — but they make up one tree, right? Or… or a triangle!”

The look of confusion on his face only deepened. For a minute his politeness warred with his curiosity, but then he blurted out the inevitable: “What’s the point of believing in three gods? “Why three? What difference does it make?”

This week, we celebrate Trinity Sunday, and try, for better or for worse, to contemplate the very question my neighbor asked me: “What difference does three make?” It’s a tough question, particularly if we take the Holy Trinity for granted (Of course we believe in the Three in One!) and yet find our belief irrelevant to daily life. While most of the festivals on our liturgical calendar celebrate dramatic and suspenseful events — Jesus’s birth, the Resurrection, the coming of the Holy Spirit at Pentecost — Trinity Sunday lacks glitter. It’s abstract and boring. Just water, eggs, shamrocks, trees, and triangles. Who cares?

|

In The Divine Dance, a beautiful and transformative book on the doctrine of the Holy Trinity, Franciscan priest and theologian Richard Rohr argues that caring comes from starting in the right place: “Don’t start with the One and try to make it into Three,” he writes, “but start with the Three and see that this is the deepest nature of the One.”

Start with the Three and see that this is the deepest nature of the One. What would it look like to do this? What would we discover about God’s character, God’s personality, God’s priorities, and God’s reality, if we saw threeness as the very ground and essence of God’s being?

First, we’d see that God is not rigid and immutable. God does not exist in stasis. Rather, God’s self is dynamic and fluid. God moves. Or to use Rohr’s language again: God flows, and God is flow. God dances, and God is dance. Whether we learn to tolerate the surprise and discomfort of divine fluidity or not, we worship a God who is impossible to pin down, a God who is mysterious beyond reckoning. “Expand do not contract God,” Kenn Storck writes in his poem, “The Holy Trinity,” “For God is the Great Iconoclast.”

Secondly, we’d see that God is diverse. If God exists in three persons, then each person has his (or her) own way of embodying and expressing goodness, beauty, love, and righteousness. As Rohr puts it, the Trinity affirms that there is an intrinsic plurality to goodness. “Goodness isn’t sameness,” he writes in The Divine Dance. “Goodness, to be goodness, needs contrast and tension, not perfect uniformity.” If God can incarnate goodness through contrast and tension, then why can’t we? Why won’t we? Why do we fear difference so much when difference lies at the very heart of God?

|

Thirdly, we’d see that God is not a loner. Or as Lutheran minister Nadia Bolz Weber puts it, “This is not a ‘me’ God, but a ‘we’ God. God from the beginning is, not God as bad math, but God as community.” It’s one thing to say that God values community. Or thinks that community is good for us. Or hopes that we’ll build our own. It’s altogether another to say that God is community. That God is relationship, intimacy, connection, and communion. If God is both plural and interactive at God’s very heart — if Three is the deepest nature of the One — then what are we doing when we isolate ourselves from each other? When we decide to go it alone? When we hold ourselves back from intimacy and connection, and thus deny ourselves the expression and experience of God’s own self? If Rohr is right, and if the Trinity really is much more than a bit of dusty doctrine the early Church fought over, then we dare not take lightly the life-changing power of the communal. God is Relationship, and it is only in relationship that we experience the fullness of God.

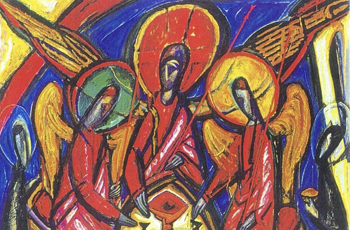

Lastly, we’d see that God is hospitality. In the 15th century, Russian iconographer Andrei Rublev created, “The Hospitality of Abraham,” also known as “The Trinity,” one of the most well known and well loved icons in Christendom. In it, the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit (depicted as the three angels who appeared to Abraham near the great trees of Mamre), sit around a table, sharing food and drink. Their faces are nearly identical, but they’re dressed in different colors. The Father wears gold, the Son blue, and the Spirit green. The Father gazes at the Son. The Son gazes back at the Father, but gestures towards the Spirit. The Spirit gazes at the Father, but points toward the Son with one hand, and opens up the circle with the other, making room for others to join the sacred meal.

|

As a whole, the icon exudes adoration and intimacy — clearly, the three persons around the table love and enjoy each other. But it also exudes openness. There is space at the table for the viewer of the icon. For me. For us. As if to say, the point of the great Three-in-One is not exclusivity — God is not a middle school clique — but rather, radical hospitality. The point of the Three is always to add one more, to extend the invitation, to make the holy table more expansive and more welcoming. In fact, the deeper the love between the Three grows, the roomier the table grows. The closer we draw to the adoration of the Three, the wider and more hospitable our hearts grow towards the world.

As I stumbled my way through a Trinity lesson that day on my patio, I didn’t get far beyond trees and triangles, but I still walked away grateful for my inquisitive young neighbor’s question. What difference does three make? As we celebrate the Trinity this week, let’s not make the mistake of ignoring the question. It’s an excellent one, and the answer is well worth exploring: three makes all the difference in the world.

Image credits: (1) Wikimedia.org; (2) Cathedral of the Incarnation; and (3) Marginalia; Los Angeles Review of Books.