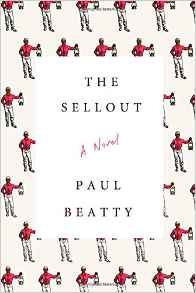

Paul Beatty, The Sellout; A Novel (New York: Picador, 2015), 289pp.

Paul Beatty, The Sellout; A Novel (New York: Picador, 2015), 289pp.

Paul Beatty won the 2016 Man Booker Prize (the first American to do so) for this bombshell of a book that was initially rejected by eighteen publishers. His scorched earth satire about race questions every stereotype and cultural assumption imaginable. It breaks every politically correct boundary that you ever feared transgressing. Nobody gets a free pass here, not "Condi Rice lying thru the gap in her teeth," not "Dave Egger's do-gooder condescension," not gang bangers, not "stupid, fat, ugly, white Republicans." And it's all laugh-out-loud hilarious.

The narrator-protagonist is a young black man named Me, who's from "a ghetto community on the southern outskirts of Los Angeles" called Dickens. It used to be a real town but has now vanished into suburban oblivion and is "turning Latino." Me intends to restore Dickens. He begins by spray painting a line around the place. He then reintroduces segregation into the bus system and the local schools. He wants to "separate the races by race," and when he does, test scores rise and life gets better for everyone. For this he ends up arguing his case before the Supreme Court, which is where the book begins and ends.

Me never knew his mother. His father was a sociologist who subjected him to wacky race experiments as a boy. Me wrote his first "scientific paper" when he was seven — "Passenger Seating Tendencies by Race and Gender: Controlling for Class, Age, Crowdedness, and Body Odor." As an adult he's an urban farmer who grows square watermelons with the help of his obsequious slave named Hominy Jenkins — an understudy to Buckwheat and the last surviving cast member of the television serial “The Little Rascals.” Me also attends the Dum Dum Donut Intellectuals that his father started, a "cabal of stupid black thinkers" who do things like rename literary classics, like Uncle Tom's Condo, The Great Blacksby, and The Point Guard in the Rye.

There's a sophisticated playfulness that drives Beatty's absurdist story — faux poetry, various fonts, mottoes in at least eight languages, lists, and charts. Although the book is mainly about being black, there's a chapter on "Too Many Mexicans," and references to Samoans, the Masai, Native Americans, Jews, and incarcerated Japanese Americans. There's also the "L.A. LGBTDL Crisis Center for Chicanos, Blacks, Non-Gays, and Anyone Else Who Feels Underserved, Unsupported, and Exploited by Hit Cable Television Shows." Beatty incorporates a remarkable breadth and depth of cultural artifacts — history, politics, art, music, film, literature, food, sports, and economics, low brow and high brow alike.

So, what's the meaning in Beatty's message? The title gives a clue, for Me himself was dubbed "the sellout" by the Dum Dum Intellectuals. Humor can be a front for rage and anger. Me observes that silence about race can indicate protest or consent, but also fear. Much of the plot revolves around Me's relationship with his father and his "Oedipal yen." There are mentions of collective guilt and self-hatred.

In one painful scene, a hip white couple is sitting in the front row laughing at the riffs of a black comedian, who then explodes at them: "What the fuck you honkies laughing at? I ain't bullshitting! Get the fuck out. Do I look like I'm fucking joking with you? This shit ain't for you. Understand? This is our thing." Which begs the complicated question — just what is "the black thing?"

David Pinckney boils it down to "the arduousness of being black, the profound self-consciousness of being black" (a theme in Margo Jefferson's Negroland). Me's father always told him that there were two important questions: Who am I? And, how can I become myself? At one point, Me envies Hominy's cluelessness. He laments "all the work" he's done to restore Dickens through re-segregation and yet "I still don't know who I am." He observes that "there's no such thing as closure." By the end of the book Me contemplates "the burden of being black and constantly having to decide when and if I give a shit about it." Indeed.