"This is Why I Have Come"

Healing and Wholeness for Body and Soul

For Sunday February 5, 2012

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year B)

Isaiah 40:21–31

Psalm 147:1–11, 20c

1 Corinthians 9:16–23

Mark 1:29–39

On the first page of the gospel of Mark Jesus begins his public ministry with two highly symbolic acts — his baptism by the Spirit in the river and his temptation by satan in the desert. These parabolic actions were like contemporary street theater. Their effect was electric. They provoked public controversy — who was this man, and what was he doing?

|

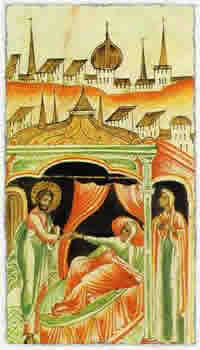

Aprakos Gospel, 1693, Jesus Heals Peter's mother-in-law. |

"People were amazed," writes Mark. News spread quickly. At Peter's mother-in-law "the whole town gathered at the door." A few days later in Capernaum the crowds were even bigger: "so many people gathered that there was no room left, not even outside the door." People kept pushing and shoving, and the stories kept spreading. As a result, "Jesus could no longer enter a town openly but stayed outside in a lonely place." It was just as well, for his habit was to rise in the early morning darkness and find a solitary place to pray.

Spirit baptism and satanic temptation were so central to the identity of Jesus that both incidents are included in all three synoptic gospels. And Jesus was crystal clear about what they meant. ”I have not come to call the righteous, but sinners.” The religiously righteous thus complained, “this man welcomes sinners and eats with them.” They stigmatized him as "a friend of tax gatherers and sinners," but what they intended as moral slander he took as divine confirmation.

With his baptism and temptation Jesus identified with people who were spiritually sick and morally impure. And when on that first page of Mark he invited people to "come, follow me," he invited us to do the same today.

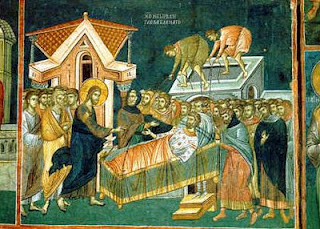

But there was more. In addition to embracing the morally impure, Jesus healed the physically infirm. He cared as much about sickness of body as he did sins of the soul. He healed the body of Peter's mother-in-law of a fever, then in the synagogue he healed the mind of a man with an unclean spirit. In the story of the paralytic man one page later, he combined the healing of body and spirit into a sort of psycho-somatic unity: "Your sins are forgiven," Jesus assured the man; and then, "get up, take up your mat and walk!"

"This is why I have come," Jesus told the crowds — to proclaim and perform God's healing of body, mind, and spirit.

|

Jesus heals the paralytic. |

And this is why every Sunday in our eucharistic liturgy the congregation confesses with confidence, rather than with fear or shame, "we break this bread for our own brokenness." Rightly understood, our confession of brokenness of body and soul is a celebration rather than a lamentation, for in it the spiritual and physical fraility of humanity meet the compassion of God.

Embracing our physical and spiritual brokenness is important because we know that not everyone experiences healing, not now and not in Jesus's day. My mother, a church organist, battled severe clinical depression the last twenty-five years of her life. Over the Christmas holidays we learned that a family friend died while waiting for a lung transplant after a long struggle with pulmonary hypertension—she was only twenty-seven.

We'll never know why some people experience healing and others don't. Instead of fruitless speculation, the fourth-century mothers and fathers offered some ruthlessly realistic consolation. "Expect trials until your last breath," said Saint Anthony the Great (251–356).

I used to think of the desert monastics as Christian super-heroes. I couldn't have been more wrong. And given that these oddball saints are so far removed from our own time, place, and culture, I kept wondering what drew me to them other than historical curiosity. A few thousand pages later I realized that I loved them for what John Chryssavgis calls their "spirituality of imperfection." They helped me to make peace with my own physical infirmities and spiritual imperfections.

The early ascetics fled to the solitude of the desert to seek what John Cassian (360–430) called "integrity of heart" or "integral wholeness." Seeking personal transformation and not mere theological information, they favored the voice of experience over theoretical claims, and human healing over book learning. But the conclusions of their spiritual experiment are not what you might expect.

With remarkable candor, brutal realism, unqualified empathy, and wry humor, they describe how in the vast nothingness of the Egyptian desert they discovered a cacophony of voices in the interior geography of the human heart. They sought wholeness but discovered brokenness. And they embraced their brokenness, says Cassian, "without any obfuscating embarrassment," and without ever "despising anyone in belittling fashion."

Cassian's Institutes and Conferences read like a modern therapist's clinical observations. He gives detailed descriptions of lethargy, sleeplessness, unsettling dreams, impulsive urges, self-justification, seething emotions, sexual fantasies, pious pretense that masked as virtue, self-deception, clerical ambition and the desire to dominate, crushing despair, confusion, wild mood swings, flattery, and the dreaded "noonday demon" of acedia ("a wearied or anxious heart" that suggests close parallels to clinical depression).

|

Jesus heals a blind man. |

And that's not the worst part. Cassian also admits that "there are many things that lie hidden in my conscience which are known and manifest to God, even though they may be unknown and obscure to me." Similarly, his friend Germanus observes how "superfluous thoughts insinuate themselves into us so subtly and hiddenly when we do not even want them, and indeed do not even know of them, that it is very difficult not only to cast them out but even to understand them and to catch hold of them."

Despite their ruthless realism about our faults and failures, the desert monks didn't live like helpless or hopeless victims. Rather, they exuded confidence in God's unconditional love. They showed tenderness and patience toward one another and to their own selves. They avoided the faintest hint of judgementalism, rejected every manifestation of extremist zeal, and chose not to compare themselves with others or even to be overly anxious about their progress. "We are," concluded Cassian, not angels but "only human beings."

In this week's Old Testament reading, Isaiah's mighty God, so Absolutely Other that he looks down upon us like "grasshoppers," is nevertheless tender in his love. Be assured, he writes, your way is not hidden from God. He never grows weary or tired; his empathy and understanding of our human frailties knows no boundaries. Isaiah acknowledges that we grow weary and weak, and that even vigorous youth stumble and fall, "but those who hope in the Lord will renew their strength." In the words of this week's psalm, God "heals the brokenhearted and binds up their wounds."

Image credits: (1) FreeRepublic.com; (2) Blogspot.com; and (3) Web Gallery of Art.