To Live in Longing

A guest essay by Nora Gallagher. Nora Gallagher is the author of two memoirs about faith and doubt: Things Seen and Unseen and Practicing Resurrection. Her new novel, Changing Light, a love story set in 1945 in New Mexico in the shadow of the atom bomb, was published this year. She is preacher-in-residence at Trinity Episcopal Church, Santa Barbara, and on the advisory board of the Yale Divinity School.

For Sunday December 9, 2007

Second Sunday in Advent

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year A)

Isaiah 11:1–10

Psalm 72:1–7, 18–19

Romans 15:4–13

Matthew 3:1–12

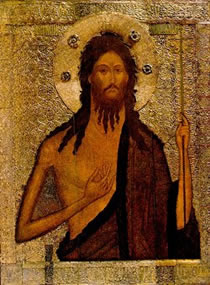

John the Baptist; 6th Century Byzantine icon. |

Here we are in Advent. The Advent season is a time of longing, of expectation, of hope for the long-awaited fulfillment of a promise. In the Advent season, we wait for the moment when heaven touches earth. That image, for some of us, is of heaven coming down from above. For others, it’s of heaven rising up, infusing our tired world with new life. The Celts called this moment—when heaven meets earth—thin space. In this season, we practice to breathe in thin space, to live in longing, to make a pathway for heaven into our hearts.

In this second week of Advent, we ponder a man crying out in the wilderness.

Each of us probably has an image of wilderness. My own is of the Brazos Wilderness in Northern New Mexico where I went as a ten-year-old child. A friend of my mother’s took four children on a pack trip, on horseback, with a Native American guide from the Taos Pueblo. It was the first time I’d been away from my mother for more than a few nights. My image of wilderness will always be that trip. It was a place of beauty and terror, of tests of courage. I learned to ride a young horse, and when that horse decided to lie down in a stream, I learned how to jump off. I learned that I had to stand up for myself against the teasing of an older boy. There were no houses and we had no maps. Sometimes the aspen trees grew so thickly together we had to put our feet up on our saddle horns. At night, the stars in the sky seemed as close as my hands, and Frank, our guide, used to sing to them in the language of his ancestors.

Wilderness. A place where there are no houses and no maps. A place of beauty and tests of courage. A place where your guide may be someone entirely different from what you expected.

Another kind of wilderness. This one in Santa Barbara, a soup kitchen where I worked for four years, housed in my church’s parish hall. We made the soup out of discarded vegetables given to us by the produce manager of a local Vons grocery store. On this salvage, we fed up to 250 people a day.

|

John the Baptist: Moscow School, 1560s. The State Museums of the Moscow Kremlin. |

In the kitchen we had only one rule: if you were obnoxious you had to go outside. We fed people with mental illness, prostitutes, the working poor, alcoholics, men and women on fixed incomes, and homeless teenagers on their way through town. Everyone was welcome.

Once a lovely woman dressed in a Kelly green cardigan and slacks, a “presentable” person, came to eat lunch. She started talking to a volunteer from the Latter Day Saints about how she couldn’t eat because someone was pointing at her head. Jackie, our volunteer, said to her very gently, “If you sit down for awhile, I’ll watch out for anyone pointing at your head. I’ll be right here, rinsing trays.”

The woman sat down and began to eat. She ate for a few minutes. Then she reached down to pick up something off the floor. When she straightened up, she said, “Someone pointed at my head while I was leaning over. Someone pointed at my head.”

Jackie walked over to her and touched her very carefully on the arm and said, “I’ll make sure they don’t do that again."

The woman smiled. Then she said, “I’m not always like this.”

Jackie replied, “I know.”

In the kitchen I saw a man barely able to concentrate because of mental illness play The Moonlight Sonata on the piano. I watched another man throw himself between two men to prevent a fight. We had so many offers to help from the men and women we fed we couldn’t use them all.

“Thank you for letting me help,” an elderly man said to me. “I need to feel useful.”

Wilderness. A different kind. In the Community Kitchen we had no maps and different guides. It was a place of great chaos and questions. In that kitchen, the moment when heaven met earth had more immediacy. We were nearer to the brink. In the kitchen I learned about the bedrock truths of the gospel: why Jesus sat down at the table with “sinners,” tax collectors, prostitutes, “nuisances and nobodies.” I learned things about faith in the kitchen I couldn’t learn anywhere else.

In this Advent season, let us all name our wilderness. Where must we go, where is the place we are called that has no maps, and different guides? Where is the place that reveals new truths, new awakenings?

In the wilderness John cries, “Prepare the way of the Lord. Make his paths straight.”

Mosaic of John the Baptist in Hagia Sophia. |

When I thought about “preparing the way,” what came into my mind was sweeping the path outside my study door. I rarely do this. Usually I’m running from one thing to the next with barely enough time to even notice the path, least of all what is on it. But when I do sweep the path, first of all, I slow down. I like to sweep. I like watching the pathway clear, the bricks emerge. Sometimes I remember watching the friend who built the path lay down the bricks on the sand. Esther de Waal, a historian of Celtic spirituality, says that one of the gifts of Celtic life was that “it was a practice in which ordinary people in their daily lives took the tasks that lay to hand but treated them sacramentally, as pointing to a greater reality which lay beyond them. It is an approach to life which we have been in danger of losing, this sense of allowing the extraordinary to break in on the ordinary.”

Sweeping the sidewalk, when I’m slowed down, to watch for the bricks, to remember the friend who made the path, becomes a form of prayer, and that in turn becomes a way of allowing the extraordinary to break in on the ordinary.

Isn’t that what we are preparing for, and awaiting this season? The extraordinary in the ordinary?

We often settle for less in our lives. We get too impressed with strength and security or with the status quo. We are not willing to stop for a moment, or go out into the wilderness. An experienced rabbi was once asked why so few people were finding God. He replied that people were not willing to look that low.

The one who is bringing heaven to earth this Advent season is the one who lights up the ordinary with the extraordinary.

John was waiting for a great religious leader, a man—he had to be a man in that day and age—who might very well overthrow the Roman empire and restore the Jewish people to their lost glory. A master, one who would cause everyone to bow down before him. John would grovel at his feet.

But the one who is coming into the world didn’t cause men and women to bow down or grovel before him. This one welcomed children, ate with anyone; he treated everyone as if they were a human being. He shared in our common life, ate our food and drink, healed the sick, the blind and the lame. And on the last night of his life, he knelt down at the feet of his friends.

The great good news of the gospel is that the world it reveals to us is upside-down from what John expected, and from what we expect.

After his conversion, St. Francis saw the world in a new way.

“He saw everything upside down,” said a theologian at Claremont College. “He was not enamored at the strength and security of well-grounded towers, walled city states and impressive cathedrals. Rather, he saw everything hanging over nothing.” Everything hanging over nothing. “And he was astonished, but grateful, that everything did not fall down.”

We often settle for less because we are not willing to take a tumble, we are not willing to stand on our heads, we are not willing to listen for the smallest, most tender voice.

The one who is coming into the world this Advent season is not an all powerful leader or an arrogant master. The one who is coming into the world kneels at the feet of his friends, washes them tenderly, and goes to his death with one last request: "You must love one another."

Love is the power that makes things, that allows things to cohere, to coalesce, to reconcile. Love is the power that creates out of the chaos and questions of the wilderness a restored and resurrected world. Love is the power that answers our Advent longing.