Hearts on Pilgrimage

For Sunday August 27, 2006

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year B)

1 Kings 8:1, 6, 10–11, 22–30, 41–43 or Joshua 24:1–2a, 14–18

Psalm 84 or Psalm 34:15–22

Ephesians 6:10–20

John 6:56–59

|

Fuquay Varina Presbyterian Church, NC. |

Some time during my high school years my father stopped attending church. He never explained why, and I never asked. To make matters worse, since my mother never drove, every Sunday he still dropped us off and picked us up at our small-town Presbyterian church in North Carolina. I still remember how awkward that felt as a teenager, seeing Dad waiting at the curb for us in his car, seeing and being seen by our neighbors with whom he used to worship.

Those of us submerged in our Christian sub-cultures—Bible studies, weekly liturgy, denominational meetings, mission projects, youth groups, summer camps, Christian secondary schools and colleges—might raise our eyebrows about spiritual dropouts, but this could reflect more about us than about them. In our enthusiasm to commend the gospel, we sometimes soften its hard edges, domesticate its subversive message, minimize its mystery, and repress uncomfortable questions. In his book What Jesus Meant, Garry Wills writes that Jesus is always "more outrageous, [and] more egregious" than we ever expect. Even if scholars found the "true and original" Jesus behind the Bible texts, says Wills, he would appear more rather than less incomprehensible to us.

John's Gospel this week provides a case in point. After recounting Jesus's enigmatic promise that "whoever eats my flesh and drinks my blood has eternal life," John includes a detail that lends authenticity to his account: "Jesus said this while while teaching in the synagogue in Capernaum." It's as if he couldn't forget the memory of the offense that Jesus provoked that day. In a candid protest to Jesus's strange discourse, some of his disciples, those who were closest to his purpose and mission, complained, "This is a hard saying, who can accept it?" Maybe they knew exactly what Jesus meant and took offense, or perhaps they were clueless. Those who were scandalized at the message then cashed in their chips: "From this time many of his disciples turned back and no longer followed him" (John 6:66). Quitting the journey with Jesus is always a distinct option.

|

Emilia Cleopas, "Many Disciples Deserted Jesus," mixed media on paper (http://www.cleopas.com). |

The "hard sayings" of the enigmatic Jesus are only one reason why some people quit the faith. I suspect that my father lost faith in the church as an institution. Others quit, or never start in the first place, because prominent conservatives like Pat Robertson contort the Gospel into a Republican agenda, while radical liberals like the retired Episcopal Bishop John Shelby Spong drain the good news of almost any specificity. Still others leave church because of boredom, legalistic pettiness, superficial platitudes, unanswered prayers, bitter disappointments, intellectual doubts, nagging questions, or life traumas that "crush the spirit" (Psalm 34:18).

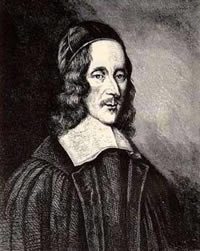

In his emotionally volatile poem The Collar, the pastor and poet George Herbert (1593–1633) considered quitting faith and the ministry altogether. Born to wealth and privilege, Herbert forsook a faculty post at Cambridge University and public service as a Member of Parliament, and in 1629 became the rector at Bemerton, a small village near Salisbury. There he spent the rest of his short life as a country cleric; a month before his fortieth birthday he died of tuberculosis.

The title of Herbert's poem evokes the stiff clerical collar that he wore; he complains that it is fairly well choking the life out of him. He begins his tirade by pounding the church altar ("the board") on which he would have served the Eucharist—wham!—and screaming what many a pastor and believer has felt but dared not express: "No more. I quit."

I struck the board, and cry'd, No more.

I will abroad.

What? shall I ever sigh and pine?

My lines and life are free; free as the rode,

Loose as the winde, as large as store.

Shall I be still in suit?

Have I no harvest but a thorn

To let me bloud, and not restore

What I have lost with cordiall fruit?

Sure there was wine

Before my sighs did drie it: there was corn

Before my tears did drown it.

Is the yeare onely lost to me?

Have I no bayes to crown it?

No flowers, no garlands gay? all blasted?

All wasted?

Not so, my heart: but there is fruit,

And thou hast hands.

Recover all thy sigh-blown age

On double pleasures: leave thy cold dispute

Of what is fit and not. Forsake thy cage,

Thy rope of sands,

Which pettie thoughts have made, and made to thee

Good cable, to enforce and draw,

And be thy law,

While thou didst wink and wouldst not see.

Away; take heed:

I will abroad.

Call in thy deaths head there: tie up thy fears.

He that forbears

To suit and serve his need,

Deserves his load.

But as I rav'd and grew more fierce and wilde

At every word,

Me thoughts I heard one calling, Child!

And I reply'd, My Lord.

Herbert's poem is full of images of constraint against which he rebels—his clerical collar, cables, a cage, ropes, laws, and his stuffy suit. He chafes at the conformity imposed upon him, and dreams about a life "free as the road, loose as the winde, as large as store." Why not flee? He grouses that his only reward for ministerial service is a harvest of thorns, and wonders whether he has wasted his years. Did he miss out on life and ambition? He regrets the pleasures and privileges that he forfeited. Perhaps he never should have left Cambridge and London for Bemerton? In the end, Herbert comes full circle. He concludes that the real "ropes," "cage," and "cables" that bind him are not the gospel or ministerial servitude but his own "pettie thoughts." In fact, the more "fierce and wilde" he raved, the more in his heart of hearts he "heard one calling, Child!" The poem ends with a robust recommitment of faith to "My Lord."

|

George Herbert. |

Some interpreters detect a note of self-pity in Herbert's poem, or even deliberate exaggeration for rhetorical effect. I read his poem at face value as a refreshingly candid expression of the deeply human questions that normal people ask on the journey with Jesus. Authentic spirituality includes rather than excludes whatever is bothering you most. In his interior dialogue with himself, I imagine Herbert weighing the words of Jesus from John's Gospel: "Do you want to leave too?" (John 6:67).

We need not solve every problem or answer every question to stay the faith. We can let the "hard sayings" of Jesus stand without softening them, or perhaps even understanding them. Trusting in God's providential call upon our lives, we can follow Herbert's advice to "leave thy cold dispute of what is fit or not." The two psalmists for this week remind us that God is "close to the brokenhearted, and saves those who are crushed in spirit," and that what we need most of all is to keep our "hearts on pilgrimage" (Psalm 34:18; 84:5).

For further reflection:

* What keeps you from faith and the faith?

* In your experience, why do people quit the faith, or never start in the first place?

* Consider Joshua 24:15: "Choose for yourselves this day whom you will serve."

* Contemplate Peter's words in John 6:68: "Lord, to whom shall we go? You have the words of eternal life."

* See Phillip Yancey, Church; Why Bother? (1998), and Soul Survivor; How My Faith Survived the Church (2001), or Garry Wills, Why I Am a Catholic (2002).